Groww Has To Find More Ways To Get Paid

India's largest broker and the search for more revenue streams.

Groww became India’s largest broker by active clients through deliberate, methodical execution over a relatively compressed timeframe, holding roughly 27% market share while Zerodha, the runner-up, now sits at about 15.4%. Groww only started its broking push five years ago, which makes the scale of its achievement worth pausing on.

Everyone in consumer finance insists distribution is the hard part, the expensive grind that breaks young firms before they can find product-market fit. Retail broking in India in many ways inverts this logic because distribution is the product. If you own the app people open by default, you own the funnel, the brand, the habit, and monetisation should follow.

Groww’s problem — and at large, the Indian broking business’ problem — is that a large chunk of what it distributes doesn’t pay: about 50-55% of client assets don’t earn any revenue. Even if you try to monetise mutual funds “properly,” the pool itself is structurally constrained, as roughly 48% of mutual-fund flows are already “direct,” leaving only about half the market where a platform can earn distribution economics. The MF-heavy mix is not just a temporary revenue gap but a smaller monetisable surface area than the headline AUM implies.

Groww’s growth has been extreme — roughly 85% CAGR over FY23-25, higher than most public companies and nearly all new-age startups — but the monetisation gap shows up where it always does in broking: ARPU (average revenue per user) and activity. Market share in accounts is not the same thing as market share in wallet, because AUM per client might look comparable to peers, but the mix matters enormously.

The industry’s secret is that accounts are not the same thing as durable engagement: an industry executive told me that only about 5-20% of new traders remain meaningfully active over time, and the rest wash out after the market teaches them a lesson. ‘Distribution wins’ can be mirages unless they translate into persistent activity and wallet share, and distribution-as-destiny only works if it converts into revenue density without poisoning the UX that enabled distribution in the first place.

Groww built a funnel through mutual fund distribution, amassing roughly 1 million customers via MFs before it even launched broking, and those users fed into brokerage adoption later. The UI/UX advantage was reinforced by an in-house tech team of 500-600 employees, and customer acquisition leaned heavily on word of mouth, as about 80% of customers were directly acquired.

Jefferies on Friday framed Groww as pulling a Robinhood, launching products and features until the revenue mix diversifies and ARPU climbs. The brokerage’s model runs on three assumptions: clients age and assets grow, as about 45% of Groww’s clients are below 30 and clients on the platform for 3-4 years have seen their assets rise 4-5x; there’s headroom for cross-sell, since nearly half of users are “only one product” users; and revenue mix becomes less dependent on basic broking over time, as Jefferies expects “new initiatives” — MTF (margin trading facility), wealth, and others — to become meaningful contributors by FY28.

MTF is where economics get real because it transforms activity into a spread-like revenue stream. Groww’s MTF market share currently sits at roughly 2%, below its retail cash market share, which is the runway argument. The MTF book stood at nearly ₹17 billion ($190 million) in 2QFY26, and projections put it at ₹90 billion ($1 billion) by FY28, implying about 6% market share — still below the cash equity share Jefferies expects by then. Even if cash-equity broking is commoditised, lending against portfolios isn’t, and MTF is a way to monetise “serious” users without explicitly raising brokerage fees.

Groww bought its way into wealth management through Fisdom, a deal that closed recently for ₹9.61 billion ($107 million) at a trailing EV/revenue of 5.9x. Fisdom brought ₹100 billion ($1.1 billion) in AUM, a client base of 350,000 including 6,000 HNIs holding more than ₹2.5 million ($28,000) in assets, and 180 relationship managers.

Jefferies expects Groww to “platform” this into a more scalable, robo-led model for mass affluent users, forecasting wealth AUM rising to roughly ₹750 billion ($8.4 billion) by FY30 and revenues of ₹6.6 billion ($74 million), about 6% of operating revenues.

The top 1% of households control roughly 60% of household assets and about 70% of household financial assets, meaning the paying wallet in India — and many other countries, for that matter — is concentrated. The platform that graduates users into that segment gets paid very differently from the platform that simply onboards them. One of the ideal situations for Groww would be building a one-stop wealth solution that stacks distribution fees, advisory fees, net interest income from loans against assets, and transaction-linked revenues.

Groww’s Adj. EBITDA margin rose from 36% in FY23 to 59% in FY25. Marketing spend sits at ₹4-5 billion ($45-56 million), about 12% of FY25 revenue, and in-house tech lowers vendor costs while protecting UX control. Groww is spending heavily on technology at roughly 11% of operating revenues, higher than many fintech and consumer-tech peers at around 5%.

If this is “Groww means Robinhood,” the Indian version will rhyme rather than repeat. Jefferies lists possible white spaces including unlisted shares, insurance, credit cards, and subscriptions, referencing Robinhood’s “Gold subscriptions” at roughly 15% of revenues as a conceptual pointer for subscription monetisation.

Achieving any of these meaningfully may be difficult at Groww’s current state. Industry participants estimate that Zerodha has cornered a material portion of more tech-savvy and sophisticated customers.

Regulation adds another layer of complexity: if Groww’s monetisation plan leans too hard on high-frequency retail derivatives, that’s a skyscraper on policy sand. Credit carries its own risks, as Groww’s in-house NBFC has a ₹13 billion ($145 million) loan book, primarily personal loans, and incurred credit costs of 7.4% in FY25 due to write-offs. Wealth will take time, because Fisdom’s current economics are human-heavy, and turning that into scalable advice without becoming a mis-selling machine will require a delicate skill.

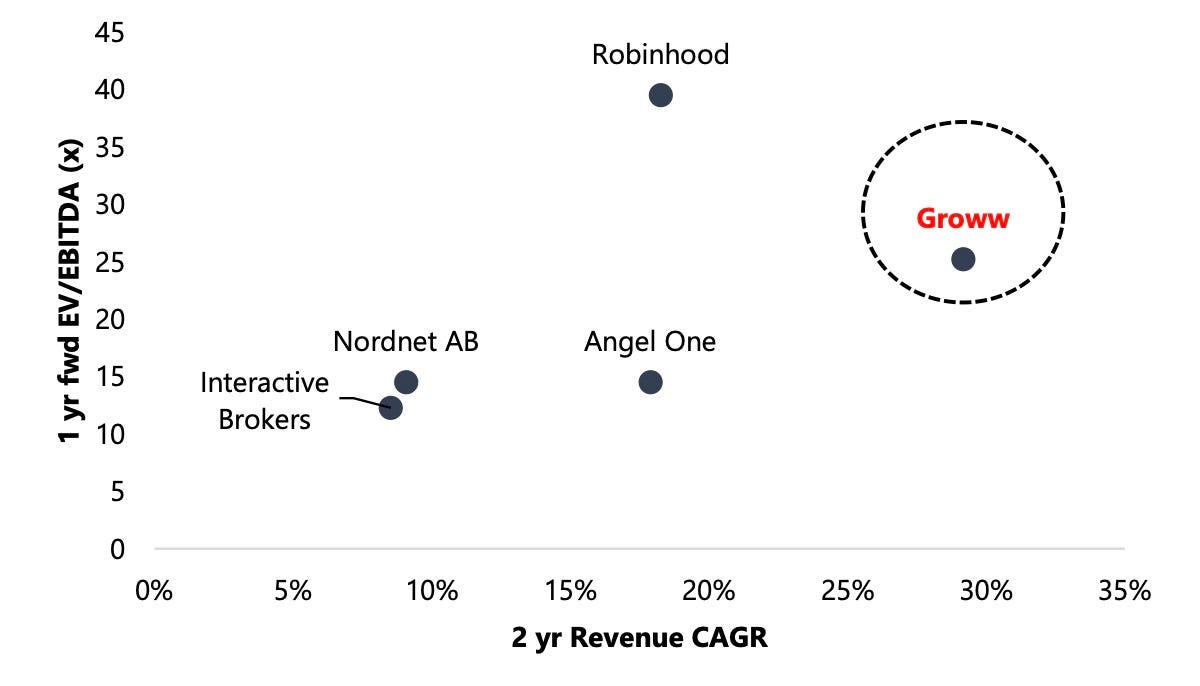

Jefferies argues Groww trades at a discount to Robinhood despite better growth and margins on its numbers, and that the discount narrows if MTF and wealth scale. Even the IPO proceeds “use of funds” list reads like a monetisation roadmap: cloud infrastructure, brand and performance marketing, NBFC funding, MTF investment, and acquisitions.

Groww’s distribution win is real, but broking market share is a vanity metric unless it turns into ARPU, and ARPU requires monetised products that users accept, regulators tolerate, and risk teams can survive.

Good one, Manish!