India and the Art of Selling Tomorrow

Wall Street's perpetually rosy forecasts for India are almost always wrong

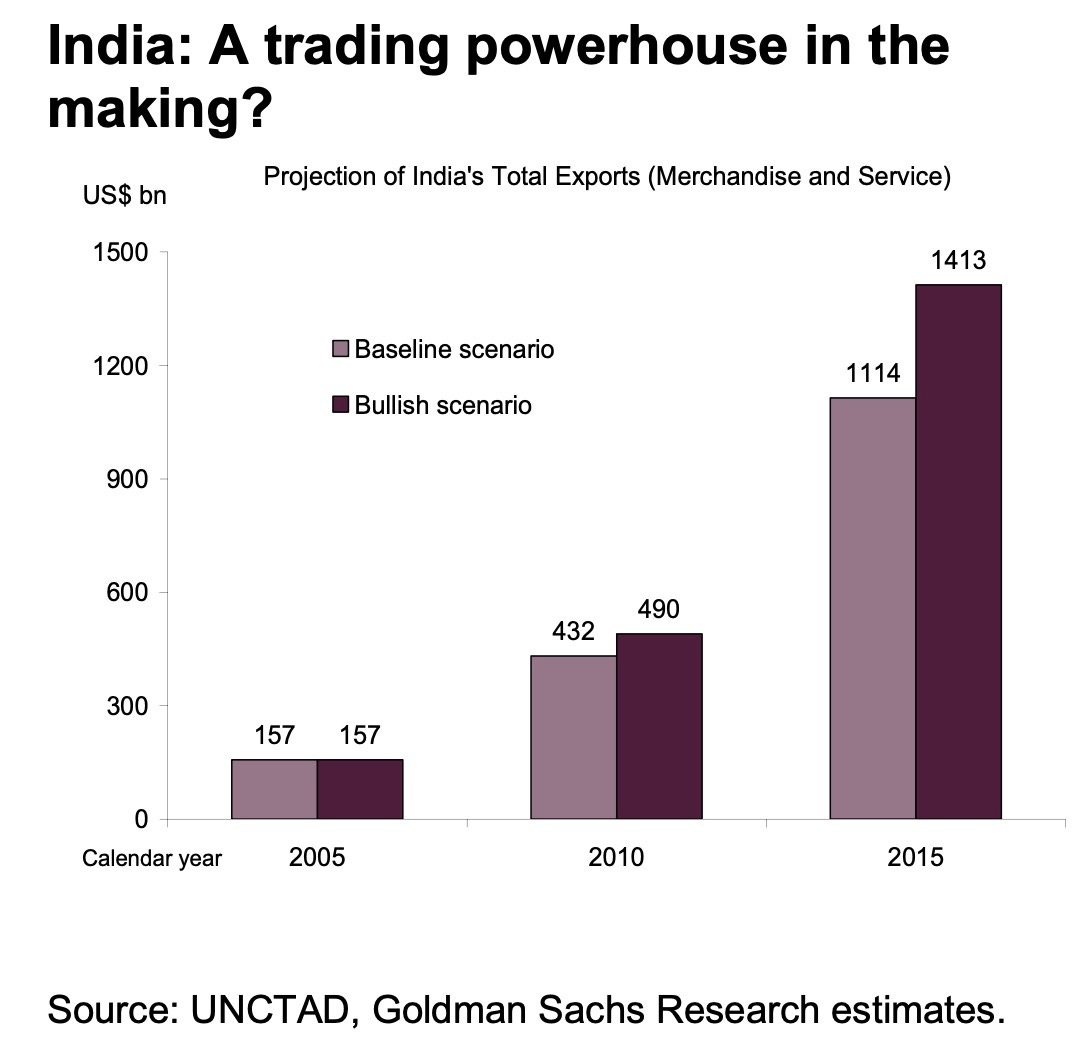

In 2007, as the world economy teetered, economists at Goldman Sachs were gazing east. India, they declared in a magnum opus, would sustain 8% annual growth right through to 2020. Not to be outdone, their colleagues in the Asia division projected that the country’s exports would touch $1.4 trillion by 2015. This would have required India to conjure up a Chinese-style manufacturing juggernaut in under a decade, but without China’s infrastructure, skilled labour, or political cohesion. The actual number, when it came, was a mere quarter of that.

Such spectacular misfires are not exceptions in the story of investing in India; they are the rule. For two decades, Wall Street’s research machine has been churning out an unshakeable narrative of a subcontinent on the cusp of a glorious transformation. The story remains the same; only the spreadsheets change when reality delivers an embarrassing fact-check. To read these reports chronologically is to receive a masterclass in how financial narratives are manufactured, marketed, and hastily rewritten. They are less a guide to India’s future than a map of Wall Street’s own dreams — and its pathologies.

The story began, as it often does, with telecoms. A 2002 Goldman Sachs report laid out a thesis that seemed unassailable: favourable demographics and falling costs would create a mass mobile market, swelling from 30 million subscribers in 2005 to 67 million by 2010. By 2005, Credit Suisse had identified an even more powerful catalyst. Chinese factories, it noted, were churning out handsets so cheap that even a subsistence farmer could justify the purchase. This supply-side revolution, not just demography, would light the fuse.

And for a time, the numbers seemed to justify the hyperbole. During the mid-2000s boom, Morgan Stanley observed that even amid the 2008 global crisis, India was adding an astonishing 10 million mobile users a month. Yet the same report noted that penetration was just 22%, compared with China’s 48%. To an analyst, that gap was not a warning, but an invitation — a vast headroom for growth, and a dangerous template for extrapolation.

This optimism was not built on sector analysis alone. It stood upon an intellectual scaffolding provided by the big-picture macro teams. In a breathtaking 2010 calculation, Goldman Sachs projected that emerging-market equities would command a majority of global market capitalisation by 2030. To get there, they argued, institutional investors would have to lift their allocations from 6% to 18%. The convenient implication was that a tsunami of capital was destined for shores like India, requiring extensive intermediation from the very firms producing the forecasts.

Sector analysts then decorate this grand architecture with the appearance of bottom-up rigour. They produce precise-sounding projections on subscriber counts, revenue multiples, and total addressable markets sized to the decimal point. The exercise is then packaged into experiential marketing. J.P. Morgan’s 2003 “India tour” offered a week-long immersion in subcontinental possibility, where dozens of company meetings created a sense of momentum designed to overwhelm sceptical analysis.

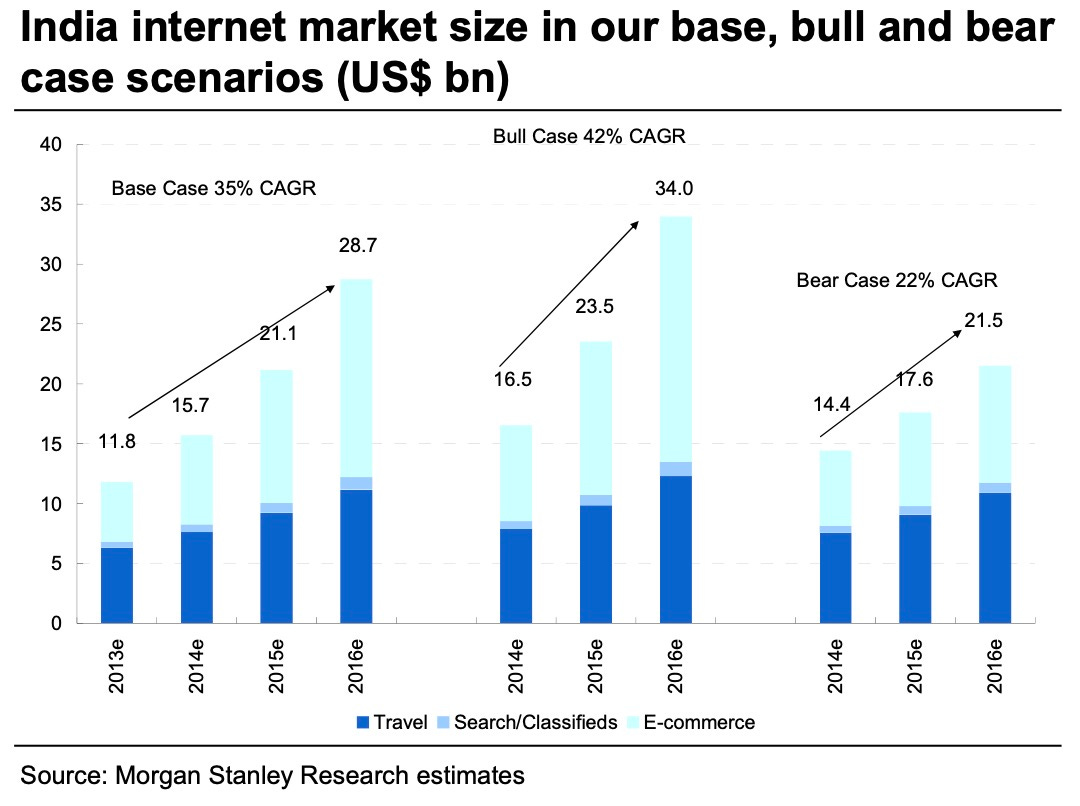

Eventually, reality intrudes. By 2014 the narrative had transitioned from connectivity to digital commerce. A Morgan Stanley internet blueprint forecast India’s e-commerce market would compound at 50% annually. Nomura’s analysts, reaching the apotheosis of analogy, declared that India in 2014 was “like the US in the mid-90s,” as if a nation with hundreds of millions in poverty could be mapped onto Silicon Valley’s suburban boom.

This comfortable world exploded in 2016. Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Jio launched with months of free service and data prices that turned the industry’s carefully calibrated economics into rubble. The response from the analysts was swift and brutal. Goldman Sachs slashed its revenue assumptions for incumbent operators by 45% overnight.

Yet, remarkably, the overarching narrative persisted. India’s digital transformation remained inevitable; it would just be bloodier and less profitable. In a masterclass of narrative reconstruction, Goldman coolly pencilled in 90 million 4G subscribers for the disruptive Jio within five years, as if destructive competition had always been part of the plan.

This period exposed a deep schizophrenia in valuations. As J.P. Morgan noted in 2015, public investors were fleeing listed internet companies as losses mounted, while private venture capitalists were pouring billions into startups. The disconnect revealed the two sides of the hype cycle: VCs could chase “winner-takes-all” theories with other people’s money, while public markets still demanded quaint things like cash flow. It was a valuation arbitrage that would eventually collapse, but not before extracting enormous fees.

To dismiss these reports as mere propaganda, however, is to miss their true utility. Their value lies not in their projections, but in their architecture of risk. The best of them maintain an honest ledger of dependencies. Those early telecom primers correctly identified that spectrum auctions and interconnection rates would determine whether reality matched rhetoric. Morgan Stanley’s internet study, for all its fantasy valuation charts, spent more time dissecting India’s glacial monetisation rates and bewildering language diversity.

The India experience underscores a broader truth about how capital markets function. A story of macro inevitability provides the foundation for micro extrapolation. Competitive reality then demolishes the spreadsheets. This forces a rapid narrative reconstruction that preserves the long-term dream while jettisoning the failed medium-term numbers. You learn to value these reports for their inadvertent honesty — the careful mapping of triggers and break points that reveal what analysts actually worry about, versus what they are paid to promote. The most revealing moment, for both companies and their investors, is when the market structure suddenly changes. That is when you know the spreadsheets are about to be wrong in a way that destroys capital, not just reputations.

Feel for you if you read multiple reports from these “analysts” to write this. Even the headlines these predictive reports make put me to sleep .