India's Got Time

While the West and China confront the fiscal drag of ageing, a 30-year demographic window offers India a unique policy runway

The strongest case for India is not merely that it is young, but that it still has time, and it may be the only continental-scale economy that still has it in abundance. This temporal advantage stands in stark contrast to China, which is crossing the threshold for an “old” country — a median age of roughly 41 — right about now, while India is not projected to reach that point until the late 2050s.

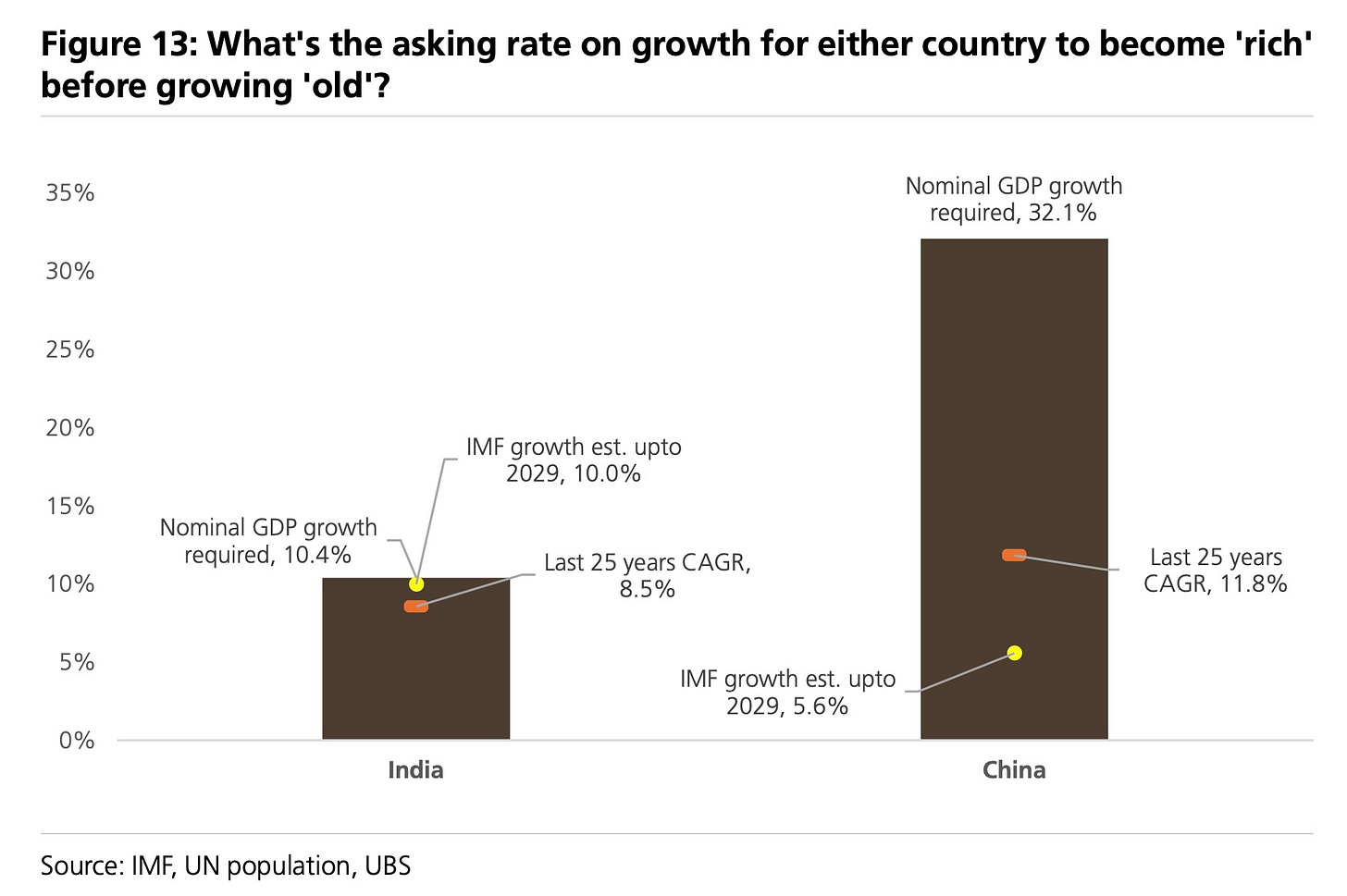

To become rich before it finishes growing old, China would now need a breathless sprint of 32% annual GDP growth, while India faces a gruelling marathon, requiring a more plausible, though still demanding, 10.4% sustained growth rate over 35 years.

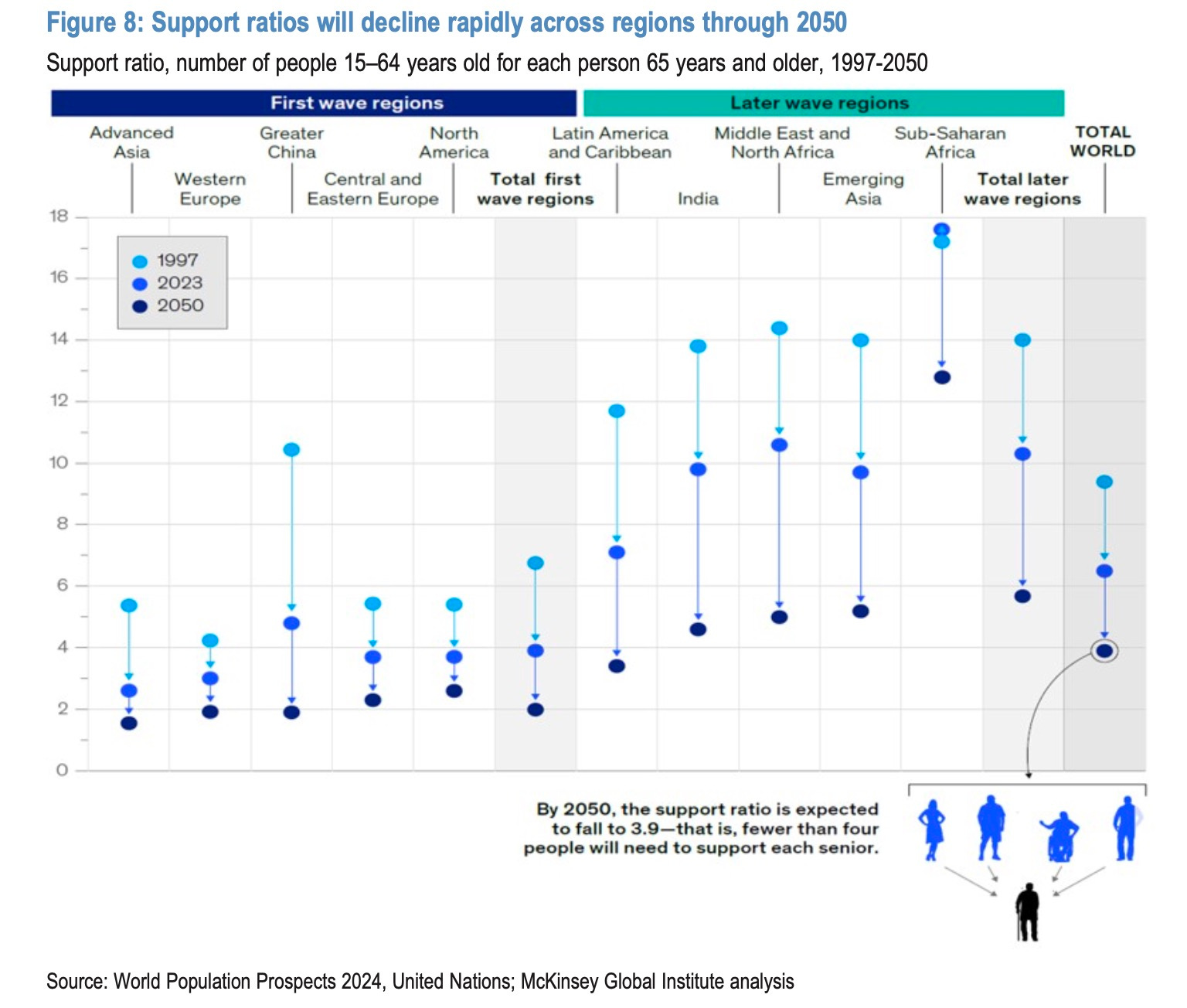

China’s compressed dilemma mirrors what is gripping the developed world, where Europe’s share of population over 65 is on track to hit 30% by 2050, up from 8% in 1950. Raising retirement ages — what economists describe as the closest thing to a silver bullet — faces older voting blocs, who now make up roughly 40% of those who turn up at the polls in European elections. In the U.S., what J.P. Morgan analysts term a “Social Security cliff” looms by 2033, when the system’s trust funds are projected to be exhausted, and hopes that productivity miracles (powered by, hopefully AI) will quietly square this circle look optimistic, leaving much of the rich world and North Asia out of time.

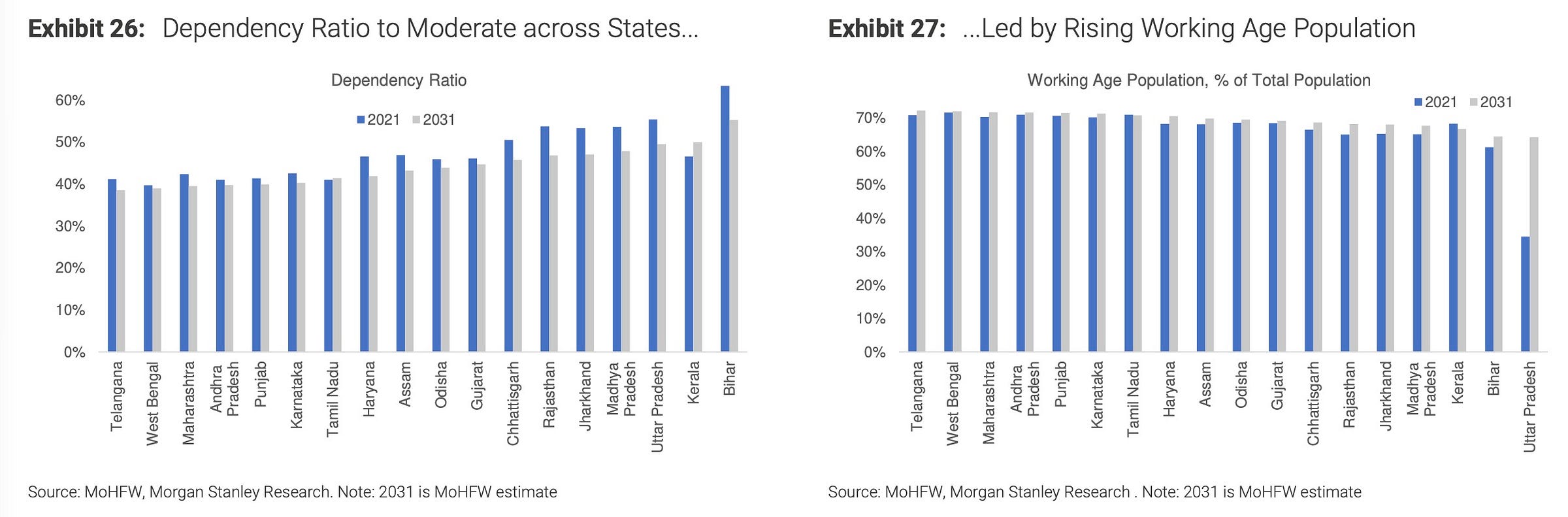

India’s working-age population is set to rise from 67.5% in 2021 to 69.2% by 2031, while the total dependency ratio — the number of children and retirees each worker must support — is projected to fall from 48.2% to 44.1%, with the median age nationwide projected to be just 34.5 in 2036, keeping a youth bulge flowing through the labour market for years to come.

Yet for all this potential, the dividend remains mostly option value, nowhere more evident than in the labour-force participation rate for women, at roughly 42%, which languishes far below the 79% rate for men, leaving an extraordinary amount of economic potential untapped. That this figure is not a ceiling is proven by states like Chhattisgarh, where female participation reaches 59.5%, while the national gross-enrolment ratio in higher education sits at only 28%, against a 50% goal.

India is not one demographic story but a portfolio of different futures, with states ageing at vastly different rates that create powerful internal economic logic. By the mid-2030s, Tamil Nadu’s median age is projected to be around 40.5, while Bihar’s will be closer to 28, a gap that raises the return on inter-state migration and encourages capital to chase younger labour inland. While Telangana boasts India’s highest GDP per capita at $4,633, it is states like Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh that have shown the most progress in recent years.

The world’s next great cohort, Generation Alpha (born 2010-24), will come of age in an era of widespread population shrinkage, and India’s share of that cohort, at roughly 18%, matches its share of humanity, with its age pyramid overlapping with Alpha’s prime working and spending years. The right comparison is not China’s factories-plus-youth model of the 2000s; India enters the Alpha era as a services-heavy economy with lower female participation and schooling levels than China had at its manufacturing-led moment.

As age-related spending rises in the West, policy is tilting toward preserving fiscal space, directing capital toward economies where labour supply is still growing, particularly as the global support ratio — the number of workers per senior — is expected to fall to under four by 2050, from over nine in 1997, putting a premium on labour-rich economies. India’s working-age population has already surpassed China’s, a structural advantage that matters when the world is short of growth.

While my recent story on India’s electronics manufacturing was critical, highlighting how its deep reliance on Chinese technology makes the “China-Plus-One” strategy seem more like establishing a subsidiary than a true rival, looking at the situation through the lens of time offers a brighter perspective. India’s unique, decades-long demographic runway provides the crucial period needed to absorb this expertise and build indigenous capabilities.

None of this absolves India from the need for execution. The policy checklist remains urgent: boost female participation, push higher education completion, speed up formal urban job creation, and treat health as growth infrastructure, but the real demographic advantage is temporal. The West and China are grappling with the mathematics of dependency now, while their politics make textbook fixes slow and partial, whereas India’s fiscal pressures from ageing will come later, and between now and then, the country can do something most of its peers cannot: use three unhurried decades to build what others must fix in compressed time while their electorates resist.