The AI Revolution Needs Plumbers After All

How Indian IT learned to stop worrying and sell the AI shovel

For the last two years, a growing consensus in the industry has been that generative AI will kill Indian IT. The argument, to be sure, has seemed almost self-evident — if machines can write code, a $250 billion industry built on getting humans to write it cheaper has nowhere left to go. Investors have acted accordingly, and the sector has since underperformed the broader market by 30% or more.

But the Indian IT industry has spent this year pushing back. It cut margins, restructured workforces, built platforms, and told clients that AI has not transformed their enterprises because their enterprises are a 30-year accumulation of SAP, Oracle, Workday and middleware that was never designed to talk to anything. And finally, Indian IT is who you call when systems need to talk to each other.

Despite all the hype, generative AI is moving slowly. Less than 15% of organizations are meaningfully deploying the new technology at their firms, according to investment bank UBS. And the narrative about the Indian IT dying is beginning to recede. Investment group CLSA titled a note this month, “Discussion moving beyond AI,” a sign that the existential panic has subsided enough for analysts to return to debating deal pipelines and vertical demand.

Enterprise AI has underwhelmed, though of course not from lack of enthusiasm or capital. Industry players say the tech remains inadequate for regulated industries where someone has to sign off on the output. They cite “workslop,” weak governance and high error rate as reasons the gap between AI as boardroom theatre and AI as functioning software remains so wide.

In the meantime, the Indian IT companies are reporting gains from the same force that was supposed to disrupt them.

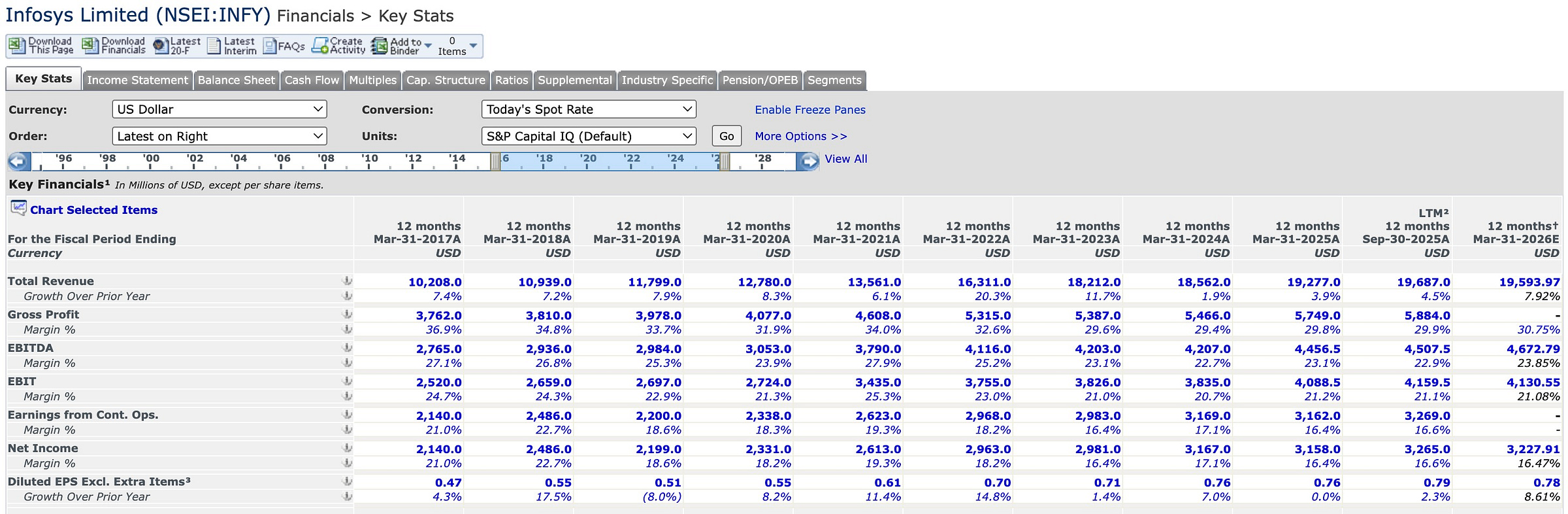

Infosys now calls AI-led volume opportunities a bigger tailwind than the deflation threat, a reversal from 2024, and orderbooks held steady in the third quarter even as pricing pressure filtered through renewals. Infosys expects its own orderbook to grow more than 50% this quarter, anchored by an NHS deal worth $1.6 billion over 15 years.

The AI capex cycle has been concentrated among a handful of hyperscalers and labs, while the Fortune 500 is still figuring out what to do with what they have bought. Indian IT is betting that figuring out what to do is billable work. Channel checks suggest a two-to-three year window of preparatory work – data cleanup, cloud migration, system integration – before enterprise-wide AI becomes feasible, and that window is where Indian IT plans to earn its keep.

The IT industry has always been reactive to new technology, late to consulting and early-stage advisory but quick to capture implementation spend once the experiments end and the plumbing needs building. The firms believe AI will follow the same arc: a hype phase they mostly miss, followed by a deployment phase where scale, client relationships and tolerance for unglamorous work become valuable again.

TCS, which cut its headcount by 2%, is spending on the “less fashionable” layers – a 1GW data-centre network in India, an indigenous telecom stack, a sovereign cloud – alongside platforms called WisdomNext and MasterCraft. It acquired Coastal Cloud, a Salesforce advisory firm, for capability it did not want to build from scratch.

HCLTech cut margins by 100 basis points, redirected savings toward specialist hiring, and became one of first large systems integrators to partner with OpenAI. The firm announced this week that it had acquired Jaspersoft for $240 million and Belgium-based Wobby to boost agentic AI capabilities. Coforge said on Friday it had agreed to acquire Encora, which offers AI tools for product, cloud and data engineering, at an enterprise value of $2.35 billion.

Infosys has taken a different route, building an asset library rather than data centres. It runs 2,500 genAI projects, has deployed 300 AI agents in its own operations and claims productivity gains of 5-40% depending on service line. Its AI-suite, Topaz, holds 12,000 assets, 150 pre-trained models and 200 agents for code generation, IT operations and billing; Cobalt holds 35,000 cloud assets and 300 industry blueprints.

Leadership now describes the systems integrator as an “orchestrator” – not building models but making them function inside client businesses, where function means plugging into SAP, Oracle and Salesforce without hallucinating key details. Forward deployed engineers sit inside key accounts to identify use cases and move pilots toward production.

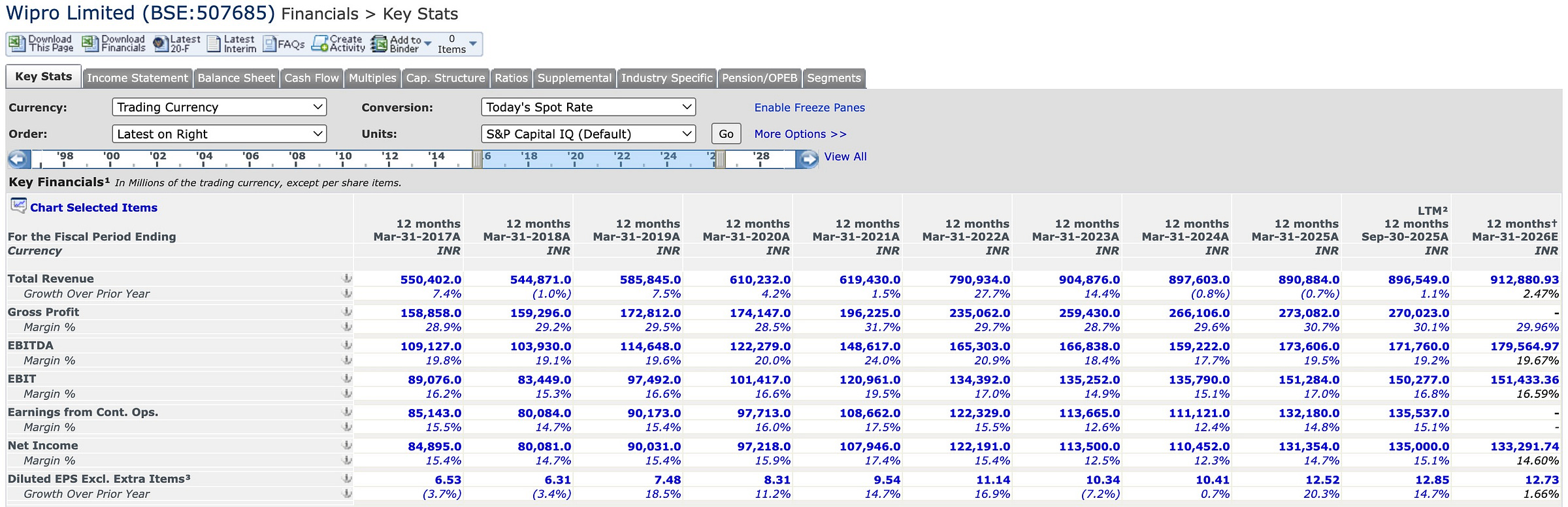

Wipro has built vertical platforms including AutoCortex, WealthAI and PayerAI and signed a sovereign AI deal with Nvidia, though the company faces stiff competition in vendor consolidation where productivity baselines already run at 15% before AI shows up. Tech Mahindra has invested in sovereign LLMs and a one-trillion-parameter domain-specific model, hoping India’s national AI push provides differentiation.

Among smaller IT firms, Persistent is reporting what it claims is early evidence of AI-driven productivity, with revenue growing at double digits while headcount stays flat. LTIMindtree has assembled an AI team of over 1,000 to build what it calls a “learning transfer” model to carry lessons from one deal to the next.

IT budgets have grown about 8% annually for the past five to six years for the industry, and the expectation is that the trend continues, with AI taking a larger share alongside cybersecurity and cloud migration.

Large customers want productivity passed through when they adopt genAI, and vendors concede the hit arrives at renewal rather than all at once, which means revenue growth may not return to mid-to-high single digits until FY28 or FY29. IT services are forecast to shrink from 38% of enterprise tech spending in 2018 to 25% by 2029, even as the absolute market grows to $1.3 trillion.

Valuations have not collapsed: the Nifty IT still trades at over 6% premium to the Nifty versus a 10-year average of 10%, and at an over 15% discount to the Nasdaq, close to historical norms. One risk for 2026 is that if the AI-led global tech rally fades, Indian IT would likely suffer rather than benefit, because relative performance has tracked broader tech sentiment even as the underlying business case has diverged.

The IT companies are not claiming victory. The argument is narrower: that the preparatory work AI requires – data cleanup, integration, compliance, tuning – creates enough billable hours to offset what automation takes away, that the middleman remains necessary for different reasons than before.

The bear case assumed AI would work out of the box, that enterprises would deploy it themselves, that Indian IT would have nothing left to sell. Two years in, AI does not work out of the box, enterprises have found it difficult to deploy it themselves, and the firms that were supposed to be dead are still hiring specialists and winning deals.

Manish makes the strategic case brilliantly—Indian IT will survive because enterprises need 2-3 years of integration work before AI actually functions at scale. The data validates it: TCS disclosed $1.5B annualized AI revenue, HCLTech is monetizing $100M quarterly in AI projects, mega-deals are landing (NHS $1.6B over 15 years).

But here's the uncomfortable second-order problem the industry isn't discussing openly: profitability depends on executing the integration faster than the competition can, because the margin is going to collapse to whoever cracks the productivity paradox first.

The real crisis hiding in plain sight:

The 95% Failure Rate is the Constraint

MIT's recent study found that 95% of deployed generative AI projects in enterprises failed to generate profits or reduce costs. UBS data shows 42% of companies abandoned most AI initiatives in 2025. But here's what this really means for Indian IT: the "2-3 year integration window" Singh identifies is actually a problem-solving sprint where the first-mover advantage goes to whoever can systematize the operationalization.

The firms solving data governance, compliance frameworks, and AI-native architectural redesign faster than competitors will establish a moat. The ones that don't will compete on price. In a commodities race with Accenture, Deloitte, IBM GBS, and each other, price always wins—and Indian IT's cost advantage depends on maintaining utilization and headcount efficiency.

The Productivity Paradox is Eroding Margins in Real-Time

Infosys claims 5-40% productivity gains from AI. HCLTech reports $100M in AI revenue but has explicitly shifted pricing to "productivity-linked fees" and "outcome-based models." Translation: the productivity gains aren't creating incremental revenue; they're reducing utilization costs on existing contracts.

Do the math: if a firm delivers 20% productivity gains on a $50M contract through AI implementation, and the client demands that productivity be "passed through," the firm is now delivering the same value with 20% fewer people, earning the same revenue on the contract it won 3 years ago. The only way to grow is to win more contracts. The risk? The client's engineering team learns the system, integrates it into their operations, and eventually internalizes what used to be a billable managed service.

The Vendor Consolidation Trap

Enterprise CIOs are consolidating vendors in 2025 (SAP's CIO Trends 2025 confirms this). They're moving away from project pricing and toward licensing, outcome-based pricing, and "vendor of record" arrangements. This is great for the vendor selected—and catastrophic for the 3-4 losing firms. It's consolidation at the supplier level, which means fewer but larger relationships, but also means the client negotiates from a position of power: "Integrate my AI faster and cheaper, or I'll find a firm that can."

What This Means for the "Indian IT Will Survive" Thesis

Singh is right that Indian IT won't die. But the industry's crisis isn't survival—it's profitability in a race-to-the-bottom integration market.

The firms that win the next 2-3 years will be those that:

Systematize the integration process (turn ad-hoc AI projects into repeatable methodologies)

Capture compliance + governance as a core capability (45% of enterprises blocked by regulatory concerns; this is a moat)

Transition from implementation services to orchestration platforms (stop being billable hours; start being a platform that clients depend on)

The firms that don't will compete on cost, margins will compress further, and the stock multiples will reflect "mature infrastructure services" rather than "AI transformation partners."

The Real Question

Singh identified the demand wave. He got the timing right. But he's written a "survival thesis" when the actual debate happening in board rooms is "how do we monetize the 2-3 year integration window before competition commoditizes it?"

The firms that answer that question—by building genuine intellectual property, replicable processes, and platform dependencies rather than project work—will trade at different multiples than those still selling time-and-materials to the SAP integration market.

TCS's $6-7B investment in AI data centres is a bet on that. Infosys's Topaz platform (12,000 assets, 300 agents, 150 pre-trained models) is a bet on that. HCLTech's explicit pivot to productivity-linked pricing is a bet on that.

The question isn't whether Indian IT survives. It's whether they can escape the margin compression cycle before the 2-3 year window closes and enterprises start building in-house.

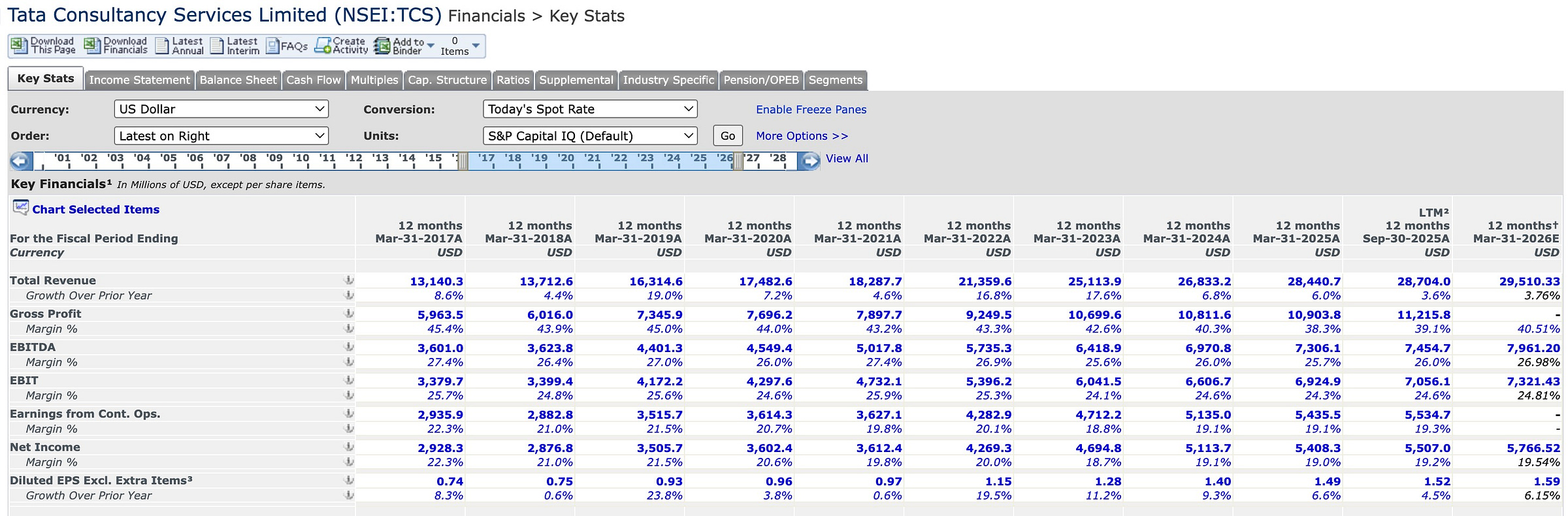

P.S. on the Data: If Singh's thesis is that AI creates 2-3 years of billable integration work, then HCLTech disclosing only $100M in AI revenue (3% of total), TCS growing just 2.39% QoY despite "AI being a bigger tailwind than deflation," and Infosys staying silent on AI revenue should concern investors more than it comforts them. These aren't signs of a booming new revenue stream—they're signs of a margin-compressing productivity cycle. The firms solving that paradox faster will separate from the pack. Everyone else becomes a commodity.

the way claude code and now, claude cowork is performing - AI does seem to work outside the box - delivering benefits/efficiency gains absolutely unprecedented. so that makes one condition true pertaining the bear case. aggravating the case further is enterprises going direct, building GCCs and hiring native AI talent to understand, contextualise, and deploy AI internally

if the long-tail of enterprises also happen to understand AI and figure out the preparatory work themselves (hard possibility), Indian IT companies really would not have anything left to sell as AI will takeover pure cost-optimisation and vendor consolidation deals that's paying the bills for the industry

i still believe the mid-cap Indian IT layer, particularly Persistent and Coforge will be increasingly relevant, and TCS + Infosys + HCL Tech in the large-cap. HCL Tech has turned around the business incredibly well since GenAI came out

articulate writing as always, Manish!