India's Tech Industry Poised To Gain From Trump's Tariff Plan

India's technology sector may emerge as a beneficiary of U.S. President Donald Trump's "Fair and Reciprocal Plan," even as the broader Indian economy braces for potential headwinds.

The reciprocal tariff proposal, which Trump announced last month with a pointed reference to India as having "the highest tariffs in the world," could impose additional duties of 6.5 to 11.5 percentage points on Indian imports. This marks a significant escalation from his first administration's approach, when India largely escaped the brunt of America's trade actions that primarily targeted China.

India and the United States have maintained a complicated trade relationship for years. Despite growing strategic partnership in defense and energy, trade frictions have persisted, with the U.S. repeatedly criticizing India's protectionist policies while India has defended its gradual approach to market opening as necessary for development.

Goldman Sachs estimates Trump's plan would shave 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points off India's GDP growth. "Under President Trump's 'reciprocal tariff' plan, we see three ways in which India can get impacted," the bank's analysts wrote, outlining scenarios ranging from simple country-level matching to complex incorporation of non-tariff barriers.

India has long maintained some of the world's highest tariffs, a stance that has drawn specific criticism from Trump, who told Modi during their February meeting: "Whatever you charge, I'm charging." Agriculture presents the most politically sensitive challenge, with India's protected dairy industry enjoying import tariffs of 30-60%.

Nearly half of India's population works in agriculture, and the sector's political power was demonstrated when it forced Modi to withdraw farm reform bills after mass protests in 2020-21. India's commerce minister Piyush Goyal recently visited Washington to advance trade agreement talks aimed at avoiding reciprocal tariffs threatened by April. India has already made concessions including cutting tariffs on bourbon whiskey, luxury cars, and Harley-Davidson motorcycles, while promising to increase purchases of US oil and gas despite having closer and cheaper suppliers in the Middle East and Russia. The US-India trade deficit reached $45 billion last year, making India America's tenth largest trade deficit partner.

However, the new tariff could paradoxically strengthen India's position in global electronics manufacturing by disadvantaging its primary competitors. This reflects India's concerted push since 2020 to become a manufacturing hub through its Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, which offers financial incentives to domestic and foreign companies to establish manufacturing operations in India.

"If the US imposes global tariffs on all countries, India's domestic activity exposure to US final demand would be roughly twice as high at around 4% of GDP," Goldman Sachs reports, potentially increasing the GDP growth impact to 0.6 percentage points in a worst-case scenario. This analysis considers not just direct exports but also India's role in supplying components that eventually reach American consumers through products assembled elsewhere.

The apparent contradiction in outcomes reflects India's unique position in the global supply chain. Electronics exports from India to the United States have more than quadrupled from $2.5 billion in fiscal year 2020 to $11 billion in 2024, with smartphones — primarily from Apple — accounting for half this value. Yet India currently supplies only 2% of America's electronics imports, compared with China's 35% and Mexico's 22%.

Trump's administration has several options for implementing the reciprocal tariffs. The simplest approach—country-level reciprocity—would add the average tariff differential (about 6.5 percentage points) to all imports from India. A more complex product-level approach would match India's specific tariffs on each item, potentially raising effective rates by 11.5 percentage points but requiring significantly more administrative work. The Office of Management and Budget has been tasked with producing a detailed implementation plan within 180 days.

Should Trump impose uniform tariffs across countries, India could gain significant competitive advantage against its major rivals. China currently dominates the American smartphone import market with over 80% share, while China and Mexico together control more than 60% of IT hardware imports. A blanket 20% tariff would substantially erode Chinese competitiveness while bolstering India's relative position.

"With ~20% tariffs being implemented across the board for all products from China/Mexico, India's competitiveness will increase," Nomura analysts wrote in a research note this week. This advantage would be particularly pronounced if tariffs apply to products that were previously exempted under past trade actions.

Labor economics further strengthen India's hand. Workers earn approximately $1.50 hourly in India versus $2.50 in Mexico and $15 in the United States. This wage differential, combined with a strengthening dollar, makes American manufacturing economically unfeasible even if India were to eliminate import duties entirely – effectively nullifying arguments for reshoring production to the United States.

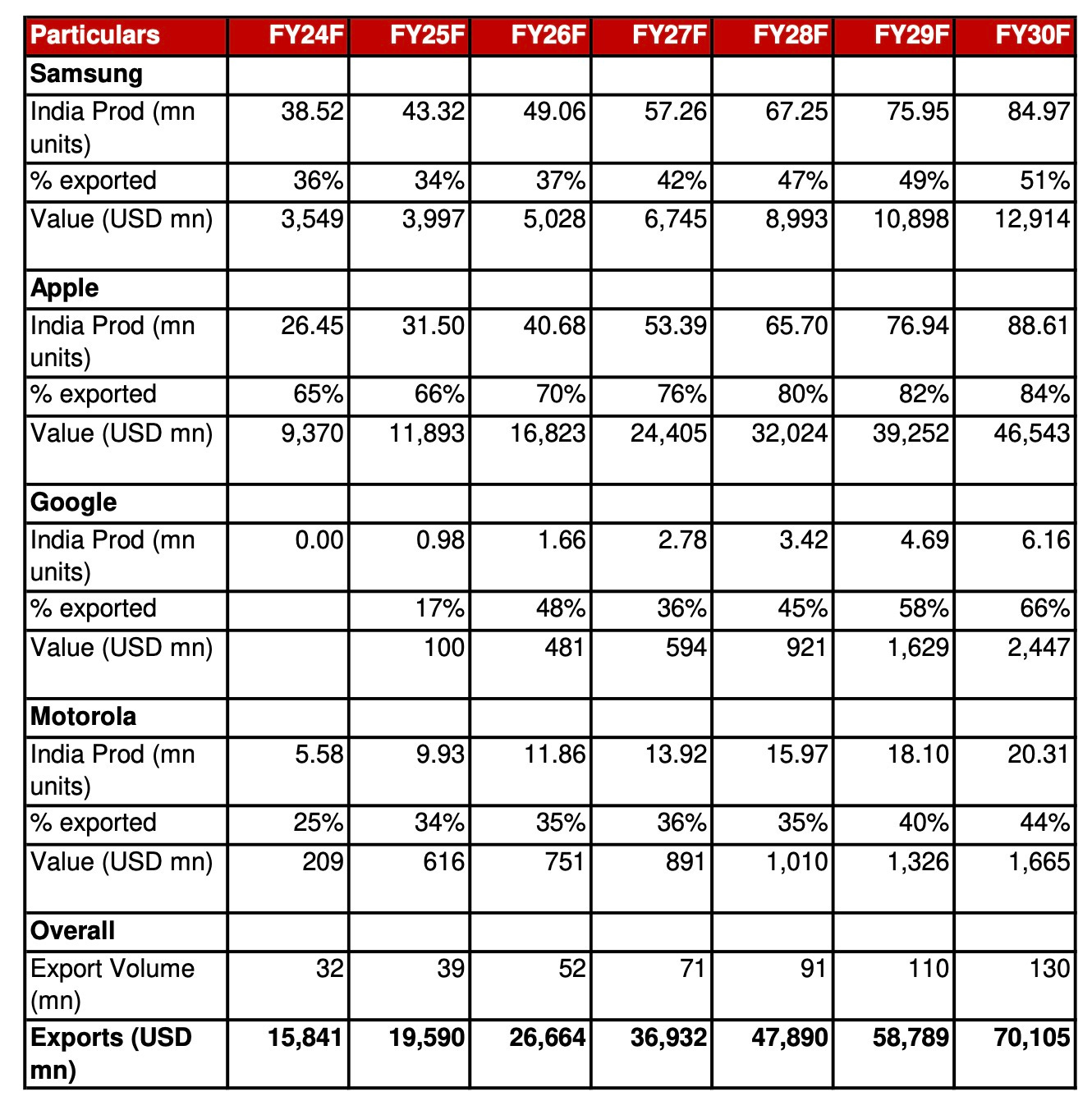

This comparative advantage explains why major technology companies have already begun repositioning their manufacturing strategies well ahead of potential tariff changes. Samsung and Apple now source 23% and 15% of their global production from India respectively, while Motorola and Google have established significant export operations from the subcontinent. Apple's shift has been particularly notable, with iPhone assembly in India growing from negligible levels just three years ago to a substantial portion of global production today.

Nomura projects that India's smartphone exports could reach $20 billion this fiscal year and potentially $70 billion by 2030, assuming a continued shift in global sourcing. This would represent a transformational change for India's manufacturing sector, which India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi has aggressively promoted through his "Make in India" initiative launched in 2014.

The complex tariff structure between the two countries creates substantial differentials. India charges 15% duties on mobile phones and 20% on consumer electronics like televisions and air conditioners, while the United States imposes no duties. However, India applies zero or minimal duties on most electronic components and IT hardware, yielding a weighted effective import rate of just 3 to 4% compared to India's overall weighted average tariff of 9.4% versus America's 2.9%.

This situation reflects India's strategic approach to industrialization – protecting finished goods while allowing duty-free import of components to encourage domestic assembly and manufacturing. The approach has evolved substantially from the pre-liberalization era when India maintained some of the world's highest tariff barriers across all categories.

India's latest budget has continued this liberalizing trend, reducing duties on completely built-up motorcycles from 50% to 30%, eliminating tariffs on lithium-ion battery components, and cutting rates on specialty steel and solar cells.

These moves come as part of a broader bilateral engagement in which India and the United States are working toward a trade deal to increase commerce to $500 billion by 2030 from the current $120 billion. This ambitious target would represent more than a fourfold increase in bilateral trade, requiring significant policy adjustments from both sides.

India's relatively modest exposure to American markets – exports to the U.S. represent just 2% of GDP compared to Mexico's 27% and Vietnam's 22% — provides some buffer against severe economic shocks while positioning the country to capitalize on manufacturing shifts in the technology sector.

For India's growing electronics industry, the ultimate question remains whether American tariffs will remain stable long enough to justify permanent supply chain reconfigurations, Goldman Sachs analysts write, which require substantial time and investment to implement. Previous experience with Trump-era tariff policies showed that even temporary trade measures can trigger lasting changes in global manufacturing patterns—potentially providing India a window of opportunity to cement its position as a major technology manufacturing hub.