Paying 230 Times Earnings

India trades like nowhere else.

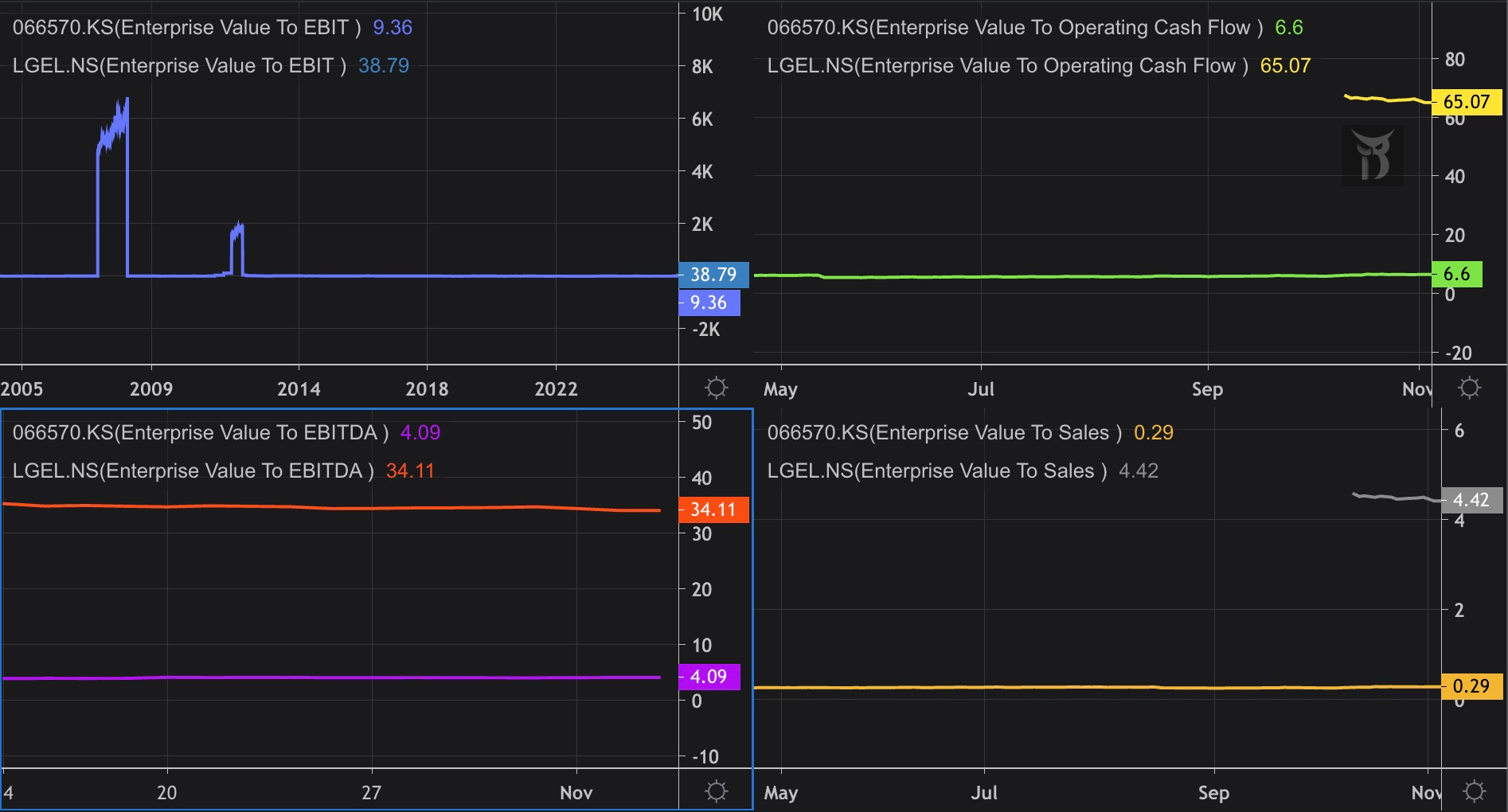

Lenskart is asking investors to value the Indian eyewear retailer at $7.9 billion, or over 230 times its earnings. The multiple has drawn criticism from retail investors. The disapproval focuses on one company, but the valuation sits within a market where extreme multiples have become commonplace.

At 230 times earnings, investors are paying the equivalent of more than two centuries of today’s profits before accounting for any discount rate.

Under a 20-year scenario, and that’s saying something, Lenskart would need to grow earnings by 26% annually for the first decade and 18% for the second decade, producing roughly a 50-fold increase in profits. Most investors price in growth over 5-10 years at most. Even during periods of peak market enthusiasm, multiples above 100x are rare and typically signal speculative excess.

Investors buying Lenskart at this valuation are paying today for what the company might become two decades from now.

Lenskart reported profit after tax of $33.5 million for the fiscal year ended March 2025. This figure includes a one-time non-cash gain of $18.8 million from an acquisition liability adjustment. The operational profit stands at approximately $14.6 million on revenue of $750 million, producing a margin of 1.95%. The company turned profitable in FY25 after losses in the prior two years.

Under a (still very generous) scenario where profits grow 50-fold over 20 years, Lenskart would need to grow operational profit from $14.6 million to $730 million. Even under that heroic scenario, it would require revenue of $37.4 billion.

The Indian eyewear market stood at $8.88 billion in FY25, according to consulting firm Redseer, which was commissioned by Lenskart to prepare a market study for the IPO prospectus. Redseer projects the market will grow at 13% annually to reach $102 billion in 20 years. Lenskart currently holds between 4% and 6% of the market and would need to capture roughly 37% of the projected market to hit the required revenue target.

Titan, which also sells eyewear in India, said this week it pegs the Indian eyewear market at roughly $3.4 billion today, growing between 7% and 8% annually. The company expects the market to reach about $5 billion by 2030.

A $3.4 billion market growing at 7.5% annually would reach approximately $14.5 billion in 20 years. Lenskart needs $37.4 billion in revenue to justify its valuation at current margins.

Under Titan’s market size estimates, Lenskart would need to capture more than 250% of the total market. Under Redseer’s projections, Lenskart would need to command 37% of the Indian eyewear market two decades from now.

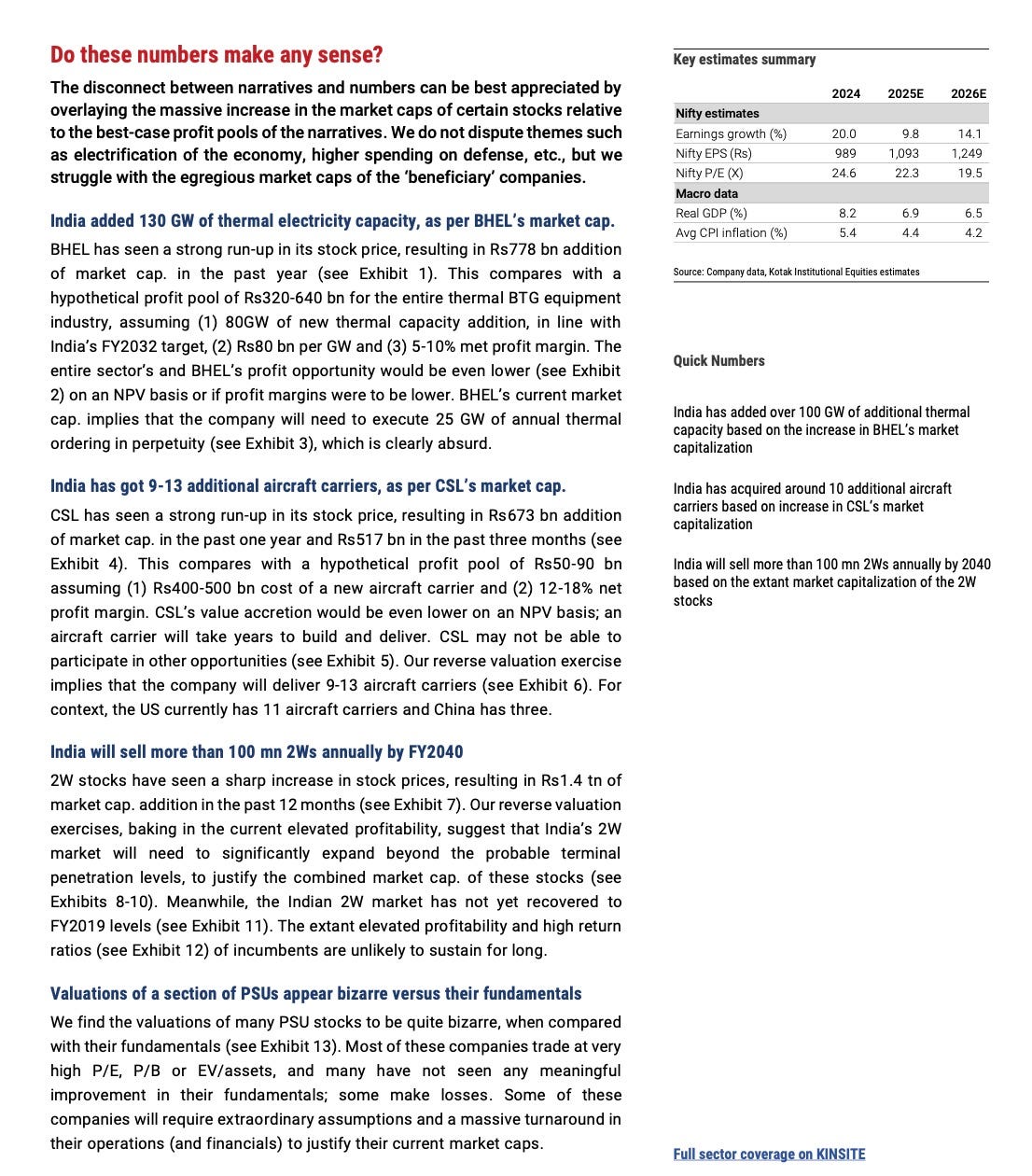

But Lenskart isn’t the real issue. Its valuation sits at the extreme end of a market where elevated multiples have become standard.

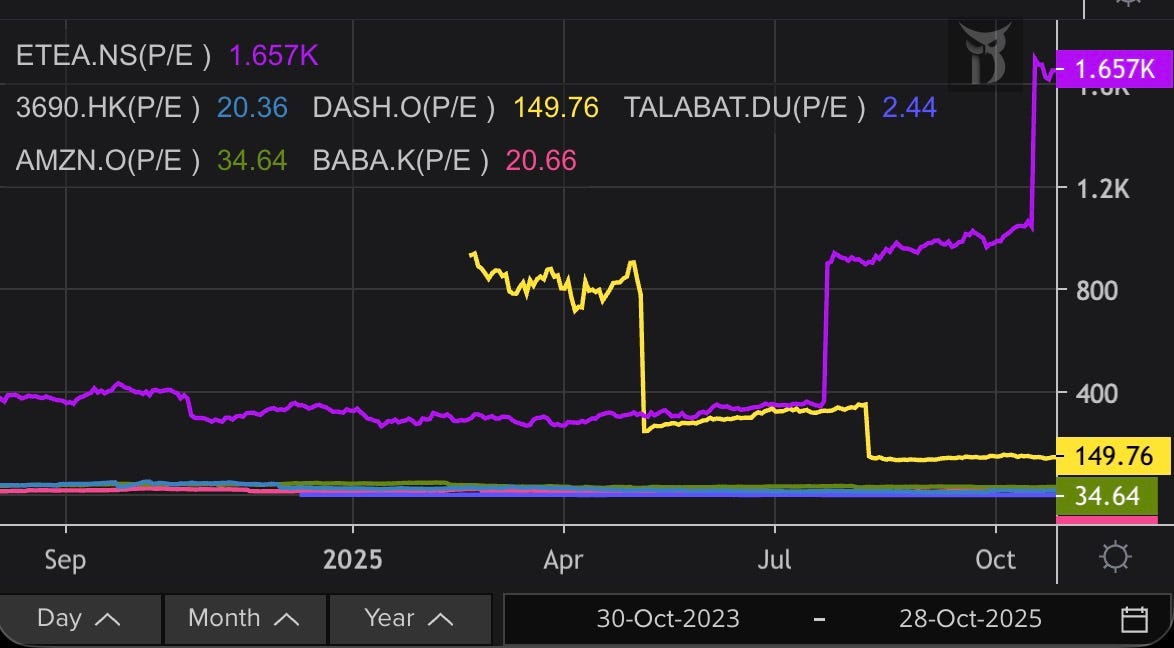

Lenskart will not be alone on the Indian stock exchanges if it commands that multiple. There are 58 companies listed on the National Stock Exchange of India with price-to-earnings ratios over 230, according to an analysis by India Dispatch. More than 180 companies trade at multiples higher than 100, compared to about 80 on the New York Stock Exchange.

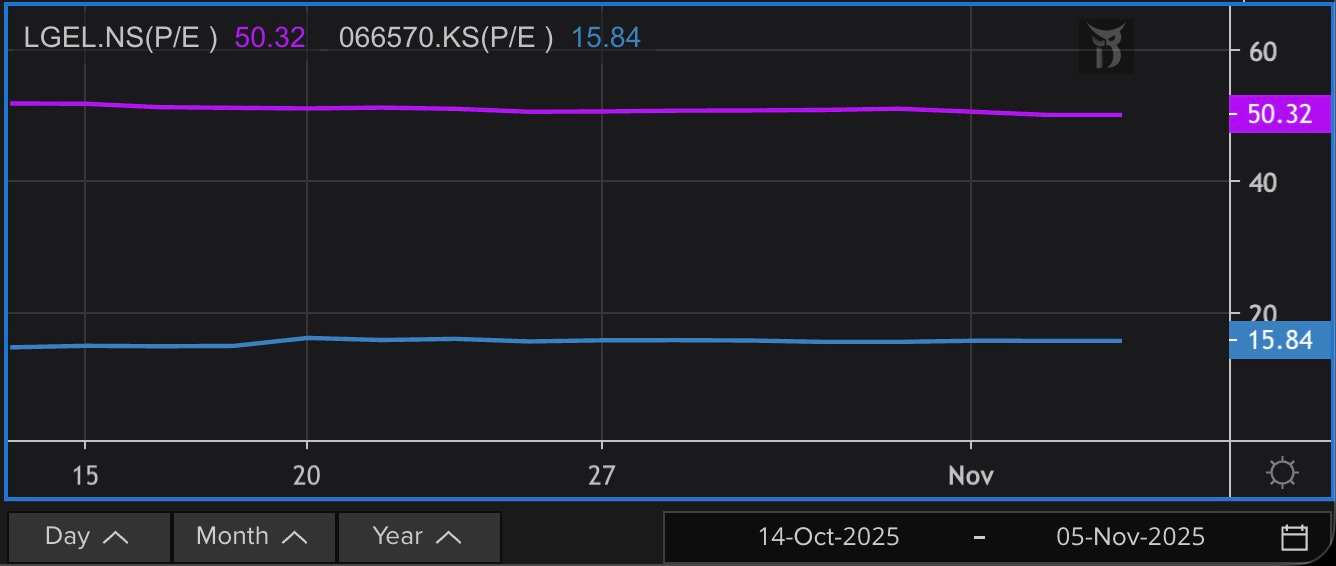

Indian stocks aren’t cheap by any measure. Right now, they trade at 25.5 times their earnings. To put that in context, when you look at decades of data on Indian stock valuations, the current multiple is higher than 87% of all historical readings. The historical average is 19.5 times.

Against other developing economies, India trades at a significant premium. The MSCI Emerging Markets index — a collection of stocks from countries like China, Brazil, South Korea, and Taiwan — trades at much lower multiples. India’s stocks are priced roughly 50% to 60% higher than this broader emerging market basket, compared with a typical premium of about 30%.

India also trades rich compared with its own history. The price-to-book ratio, which measures what investors pay relative to a company’s net assets, stands at 3.6 times versus a historical average of 3.1 times.

But here’s the thing. India’s growing weight in global indexes suggests investors are willing to pay up. Indian stocks now represent over 2% of the MSCI All Country World Index, a benchmark tracking stocks across developed and developing nations. Two decades ago, India’s weight was less than 0.5%.

In private conversations, investors and analysts argue that the premium makes sense. India has achieved something rare in emerging markets: high growth combined with falling volatility in both inflation and economic expansion. The government has consolidated its finances while the economy has reduced its dependence on imported oil. Perhaps most significant, Indian households are moving bank deposits and savings from property into stocks, a structural shift that creates sustained demand even at elevated prices.

India also offers high long-term growth potential due to low household penetration of discretionary products. When per-capita income grows, most categories from automobiles to healthcare to insurance to consumer durables could see sustained growth for many years. High long-term growth in discounted cash flow models translates to high price-to-earnings multiples.

Return ratios in India exceed those of most other major markets across sectors like automobiles, consumer staples, insurance, hospitals and banks. For automobiles, reinvestment rates and working capital requirements are lower in India. For consumer companies, return on equity is higher due to pricing power and distribution strength.

Domestic demand for financial assets exceeds supply. Less than 8% of financial investments of an Indian household are in the stock markets. In the U.S., this figure has risen to 35% at peak periods. The limited participation means more money continues to flow into equities as household wealth grows. Even China A shares command higher valuations than H shares due to higher domestic ownership. The impact becomes more pronounced when considering the low free float of Indian stocks. Average free float in India stands at only 44% compared to 67% for peers.

The final factor relates to perceived risk. Valuations factor in the earnings potential of an asset and its cost of equity. Cost of equity depends in part on the sovereign rating of a country. For India, HSBC believes the perceived risk is lower than sovereign ratings suggest. India has rarely been impacted by a sharp macro crisis, unlike many other large economies. The regulatory regime in India has been proactive in preventing economic bubbles, excluding small cycles like ILFS in 2018 and unsecured lending issues in 2008-10.

India’s structural advantages are real, and they support a market premium. But a market trading at justified premiums can still host individual valuations that make no sense. Maybe India deserves to trade richer than other emerging markets. It can also be true that a 230x multiple on a company requiring 250% of a market is detached from any reasonable outcome.

The margin gap betwee Lenskart and EssilorLuxottica tells you everything about why this valuation is stretched. Expecting a regional player with 1.95% margins to somehow achieve margins twice that of the global leader while capturing a third of a market that might not even grow as projected is pretty optimistic. The comparison to EssilorLuxottica's 11.8% on $29.9B revenue really puts things in perspective.

Thanks for putting this together - it seems that there is a need to relieve some of the demand pressure from the market. Should institutional/ retail investors be given a freer hand to allocate to global opportunities than they are allowed currently?