PhonePe's $15 Billion IPO and the Cost of Building on Government Rails

India's largest payments company has comparable financials to the rival it was supposed to have surpassed.

PhonePe filed its updated draft prospectus last month ahead of what is expected to be one of India’s largest technology IPOs, targeting a valuation of as much as $15 billion. The startup raised at a valuation of $12 billion in early 2023, when Paytm — its only real competitor — had a market cap of about $4 billion (that too, with roughly $1 billion in the bank) and a regulator bearing down on it. PhonePe was considered to be in a different league — smarter, bigger, faster-growing, dominant in UPI, untouched by the regulatory crisis consuming its competitor.

Paytm has since grown to $8.5 billion in market cap. And thanks to PhonePe’s disclosure, we now know that Paytm’s financials are comparable to, and on several metrics, better than PhonePe’s.

To be sure, Walmart-owned PhonePe has more than three times Paytm’s monthly active customers — 238 million to about 75 million — and both have roughly 47 million registered merchants. In the first half of FY26 they generated similar revenue: about $434 million for PhonePe and $441 million for Paytm. Paytm posted a profit of about $16 million. PhonePe lost $160 million.

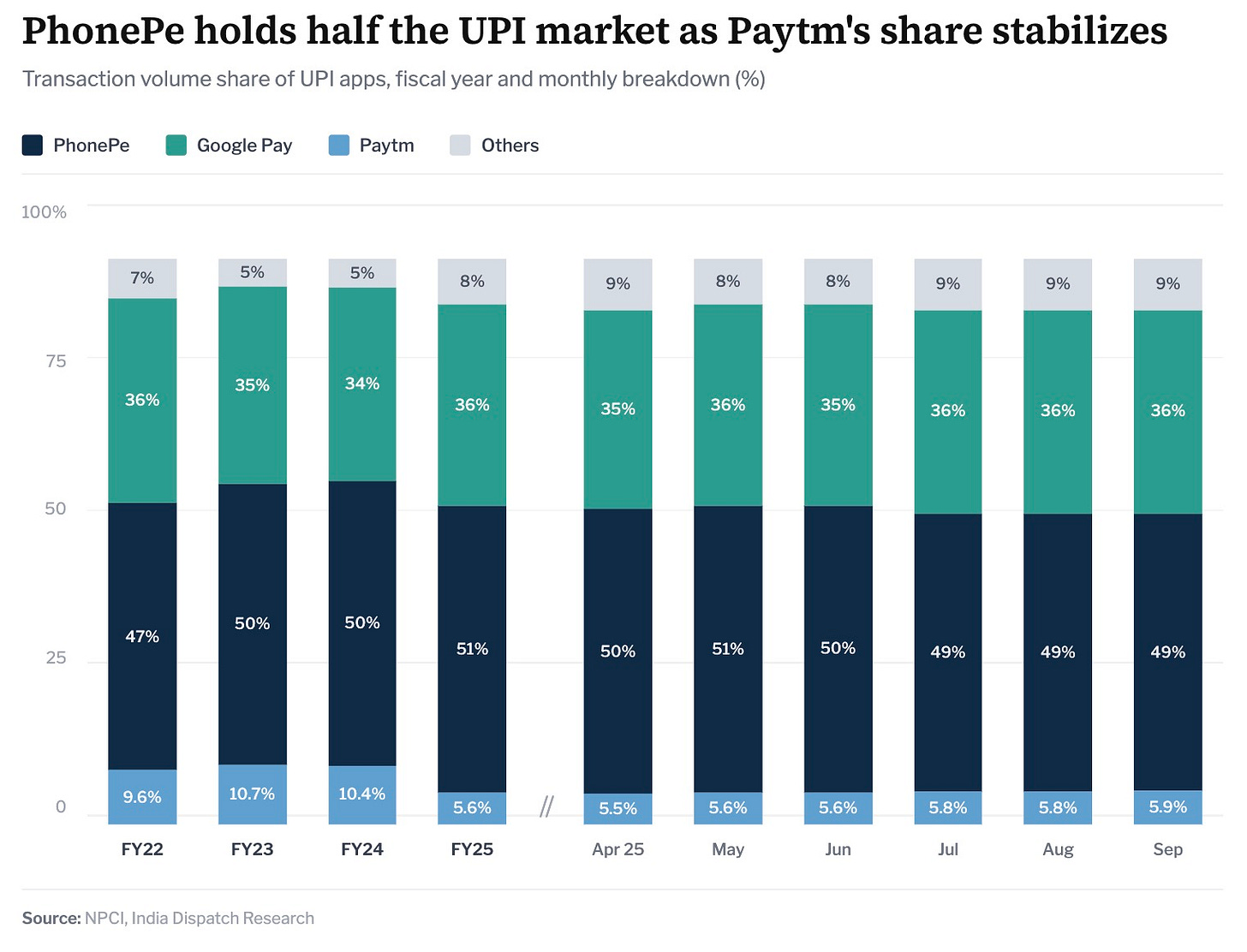

PhonePe processes about 49% of all UPI payment value on a government-built network that handles over 70% of India’s cashless transactions by value and more than 90% by volume and runs roughly $1.8 trillion in annual payment value. 82% of its H1 FY26 revenue came from payments, and while that is monopolistically impressive, PhonePe mostly cannot charge for the product.

India’s Unified Payments Interface has become the most admired piece of public digital infrastructure in the emerging world — a real-time payments network built by the government that now processes over 20 billion transactions a month and brought hundreds of millions of people into digital commerce for the first time. Countries from Singapore to Brazil have studied or replicated elements of it. The companies that scaled on top of UPI achieved extraordinary reach, but the policy regime that surrounds it wants to keep it free.

India’s Zero MDR policy, introduced in January 2020, eliminated transaction fees on UPI and RuPay payments to push digital adoption among small merchants. UPI volumes went from 12.5 billion transactions in FY20 to over 20 billion monthly transactions.

PhonePe rode that expansion to a near-majority of the market, displacing the traditional mobile wallets business, in which Paytm held the lion’s share. The government compensates payment apps through the Digital Incentive scheme, under which the Ministry of Finance reimburses a share of the value of qualifying low-value UPI merchant transactions. But it’s not ideal, as PhonePe’s updated-DRHP candidly admits: recognition of such incentives is “often uncertain and irregular.” The core of PhonePe’s payments business depends on a programme that requires annual federal budget approval to continue.

The Union Budget on February 1 — more than a week after PhonePe filed its updated prospectus — allocated $221 million for UPI and RuPay incentives in FY27 and revised FY26 allocations from about $49 million to roughly $243 million, a more than fivefold increase. Actual disbursements had fallen from $275 million in FY24 to $213 million in FY25, so the revised numbers were a relief. About 75% of incentive money on the acquiring side flows to payment aggregators like PhonePe rather than to banks.

The government’s renewed push, however, undoubtedly reduces the likelihood of MDR being introduced on UPI transactions … at least in the near future. If India does introduce MDR on UPI, PhonePe stands to generate at least $300 million in annual profit from that alone, according to India Dispatch’s analysis. PhonePe’s own commissioned research by Redseer, included in the prospectus, argues that a “carefully structured MDR regime” would strengthen the commercial case for continued infrastructure investment. The federal budget increased the subsidy instead.

The Payment Infrastructure Development Fund, a separate programme by India’s central bank covered 60 to 90% of the cost of deploying payment devices in smaller towns, expired in December 2025 and hasn’t been renewed. PIDF revenue had grown from 0.9% of PhonePe’s revenue a year earlier to 4.3% in H1 FY26 as the company scaled its device base from 2.1 million to 9.2 million. Digital and PIDF incentives together made up about 12% of FY25 revenue. The digital subsidy is now larger and the device subsidy is gone.

Regulators have not been kind to some of PhonePe’s other revenue streams, too. In September, the central bank flagged PhonePe for processing credit card rent payments to recipients who had not been onboarded as merchants, and the company shut down all rent payment services. Rent had contributed $138 million in FY25 revenue at a $52 million gross margin, up from $68 million in FY23 and $125 million in FY24.

A month before that, PhonePe discontinued real money gaming after India’s Online Gaming Act imposed a comprehensive ban, removing a segment that had produced $16 million in H1 FY25 revenue at a 94% gross margin. The prospectus put the total damage from regulatory actions over the past year at about $160 million in annualized revenue and $70 million in gross margin.

Then there are other regulatory overhangs. NPCI, which oversees UPI and RuPay ecosystems in India, has long proposed that any single app should, at max, process 30% of the UPI volume. PhonePe sits roughly 19 percentage points above the ceiling, and enforcement would prevent it from onboarding new UPI users. The original December 2022 compliance deadline has been extended multiple times, most recently to December 31, 2026. PhonePe says it “continues to engage constructively,” and there is no assurance of further extensions.

PhonePe, which has lost money every year since inception, makes money by monetizing its large user base through adjacent services including loans, insurance and mutual funds, and has attempted to expand further — an e-commerce venture called Pincode, an app store business, stock broking — but none of these have moved the needle.

PhonePe built India’s largest payments platform on government rails, under rules it cannot set, funded by programmes that require government subsidy. Paytm — which suffered from regulatory blows and directions, including government’s push to make UPI ubiquitous at the expense of mobile wallets — reached profitability under the same rules and is trading at half of PhonePe’s supposed ask.

Unless New Delhi is planning to soon bring MDR to UPI for small-ticket transactions, or PhonePe is planning to acquire a bunch of companies with its warchest and become more than a distributor, the Walmart-owned company risks committing the same mistake as its rival Paytm at the time of its IPO in 2021 — asking for too much.