The Store Becomes the Brand

Why India's biggest retailers are putting their own names on the products they sell.

In the crowded aisles of a Reliance Fresh supermarket, a shopper comparing two bags of flour sees a familiar choice. One carries the name of a well-known national brand. The other, packaged nearly identically, is Reliance’s own label — and it’s 30% cheaper. Increasingly, the cheaper bag is the one that lands in the cart.

This small decision, repeated millions of times a day across the country, is at the heart of a major power shift in India’s trillion-dollar consumer market. Retailers like Reliance Retail, India’s largest retail chain, and discount supermarket chain DMart are no longer content to be middlemen. They are aggressively launching their own brands in a direct challenge to global giants like Unilever and Nestle.

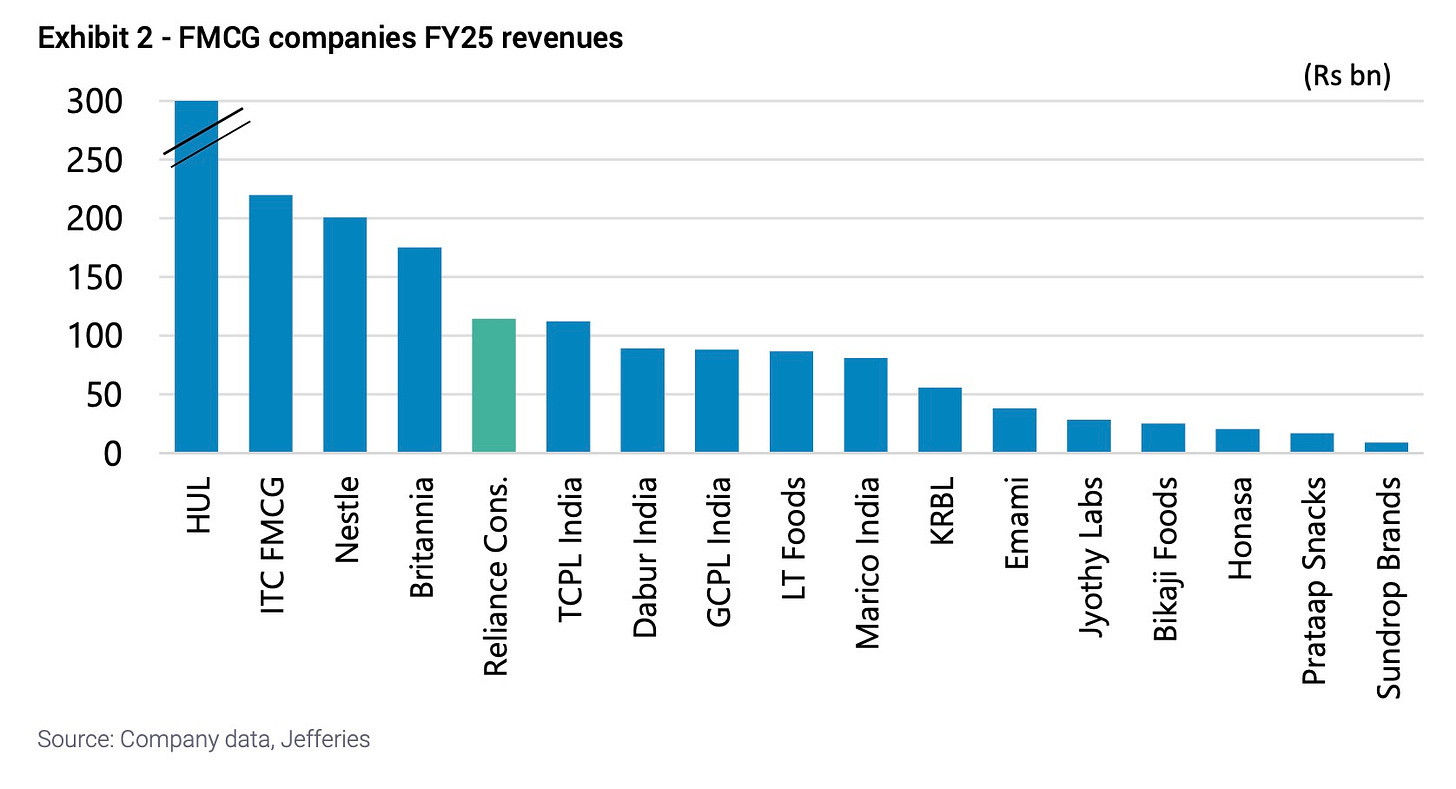

Seizing on a market with surprisingly few dominant national brands for its size, India’s retailers are using their control over distribution to build their own consumer-goods empires. In a country with 1.4 billion people, only eight consumer brands top $1 billion in revenue, per Bernstein’s count, compared to China’s dozens or Brazil’s strong regional player base. The ten largest consumer-goods firms in India reach just 4% of their addressable market — a vacuum that retailers are now racing to fill as their share of spending climbs toward a projected 40% by 2035.

This transformation diverges fundamentally from the gradual private-label evolution that unfolded across Western markets, where penetration in Europe is now 38% and 19% in the U.S. Those levels emerged over decades. In contrast, private label penetration remains low in other developing markets like Latin America (2.3%) and China (around 5%), where established manufacturers maintain dominance.

India’s retailers are leapfrogging this timeline. This shift also occurs against a backdrop where China achieved retail modernization differently, maintaining strong national brands while growing e-commerce to nearly 50% of sales. India’s retailers are using physical store control as their primary weapon.

The economics of this shift decisively favor the retailers. Traditional fast-moving consumer-goods companies in India typically spend 5-10% of their revenue on advertising and promotions, and another 4-5% on sales and distribution, plus royalties and corporate overhead.

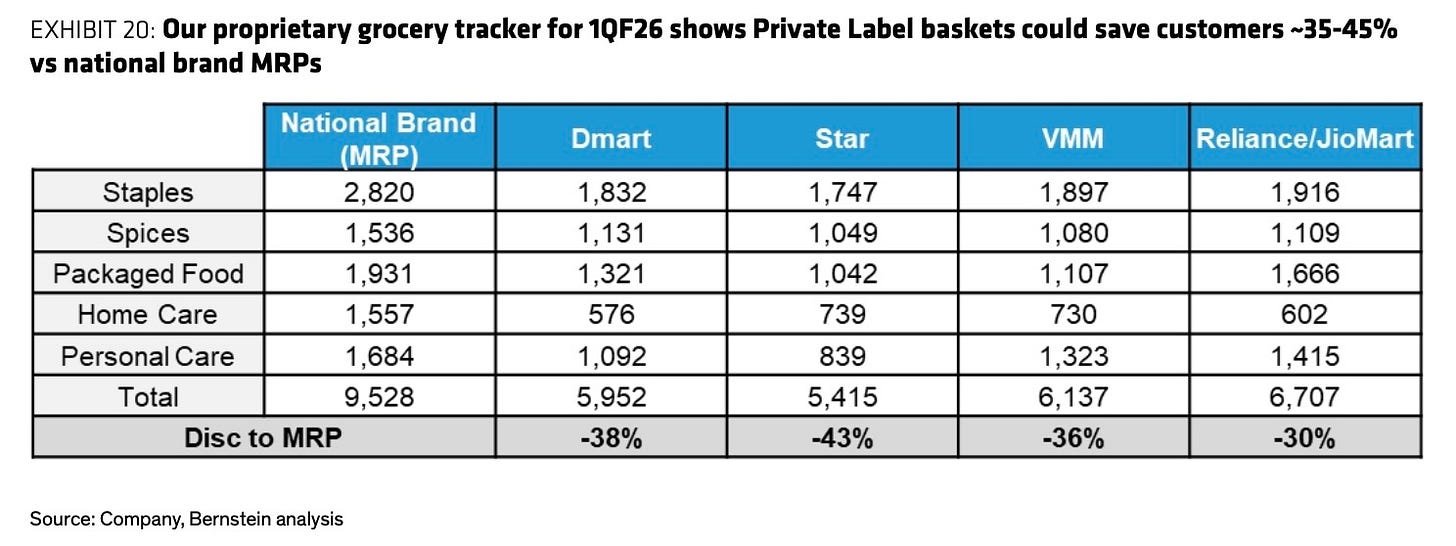

Retailers building their own brands sidestep nearly all of these costs. They convert those savings directly into lower shelf prices, with their store brands commonly priced 30-40% below national equivalents, a magnitude that surpasses even mature Western markets where price gaps average 20-28%. Shopper data confirms the strategy is working: shopping carts heavily weighted toward private labels save customers roughly 35-45% compared to the maximum retail prices of national brands.

The savings for consumers vary by what they buy and where they shop. The deepest discounts, approaching 60%, are in home care products sold in modern supermarkets, while packaged foods see gaps in the mid-30s. The hierarchy is clear: brick-and-mortar superstores offer the biggest private-label discounts, followed by e-commerce, with quick-commerce platforms offering the slimmest savings.

Retailers aren’t just putting cheaper products on the shelf; they are engineering the entire price architecture of their aisles to favor their own brands. When a chain introduces a private-label line, it often reduces the promotions on competing national brands in the same aisle.

This tactic deliberately creates a wider price gap, making the store brand a more compelling value choice. The strategy allows retailers to capture more margin from shoppers who remain loyal to the big brands while making the switch to a private label almost irresistible for everyone else.

No company has embraced this strategy more aggressively than Reliance Retail. The conglomerate spun off its consumer brands into a separate unit, Reliance Consumer Products Limited (RCPL), signaling its ambition to build a standalone consumer-goods business.

In fiscal year 2025, the RCPL portfolio hit roughly ₹115 billion ($1.31 billion) in revenue, a scale that already rivals several publicly listed FMCG companies. Two of its new brands, Campa soft drinks and Independence staples, scaled rapidly, each exceeding ₹10 billion ($114 million) in sales.

To put its scale in perspective, these consumer brands now account for about 7% of Reliance Retail’s core revenue and 12% of its grocery sales. To lead the charge, the company hired a former top executive from Coca-Cola, a clear signal of its brand-building ambitions.

Yet the strategy holds a key contradiction. To become a true “brand house” instead of just a “house brand,” RCPL must take on the very advertising and distribution costs its private-label model was designed to avoid. As long as its products are sold mainly through its own captive channels like JioMart, its costs remain artificially low. Success in selling through India’s millions of mom-and-pop kiranas and rival chains will mean its cost structure will inevitably begin to look more like a traditional FMCG company’s.

At the other end of the strategy spectrum is DMart, which uses its private labels as tools for speed rather than profit engines. The discount chain focuses on an everyday-low-price strategy for all brands, using its own grocery products simply to drive foot traffic and increase the number of items in each basket.

DMart’s gross margins hover near 15%, lower than competitors that push private labels harder. Yet its revenue per square foot is significantly higher. For DMart, a private label is a lever to accelerate how fast inventory sells, not a replacement for the price discipline that drives its business.

The contrast is clearer when looking at how much of a store is dedicated to its own brands. At chains like Star and Vishal Mega Mart, store brands can generate over 70% of sales in some categories. At DMart, that figure is kept around 20-25%. Analysts warn that pushing private labels too hard can alienate shoppers looking for familiar names and that store brands rarely succeed in creating entirely new product categories.

Retailers can compete so effectively on quality because their products often come from the same factories that make the famous national brands. Contract manufacturers that produce coffee, biscuits and instant noodles for leading companies frequently run the same production lines for retailer-owned labels. In a market where packaging often matters as much as advertising, this blurs the line for consumers and allows retailers to offer comparable quality for a much lower price. In taste tests cited by Bernstein, private labels frequently scored at or above their well-known national counterparts, demolishing the quality-based justifications for premium pricing.

For shoppers, the final calculation is the total bill. An analysis by brokerage Bernstein of a sample basket, including delivery or travel costs, showed DMart was the cheapest at ₹6,101, followed by e-commerce player Flipkart at ₹5,516. A comparable quick-commerce basket cost ₹7,764, reflecting fewer private-label options and a focus on convenience over price.

Furthermore, retailers like DMart have another quiet advantage: format economics. By often owning its store locations, DMart has lower long-term occupancy costs, which helps it sustain low prices and turn over stock rapidly. On digital platforms like JioMart, the strategy is different, using dynamic pricing to nudge shoppers toward its own RCPL brands. In one example, it launched a 200ml cola for ₹10, explicitly resetting consumer price expectations in a market where rivals were anchored at ₹20 for 250ml.

India’s consumer market remains oddly under-branded at the top and over-fragmented at the bottom. This structural anomaly creates opportunities for retailers to fill the vacuum themselves. The comparison to China is instructive, as that market developed powerful national champions before modern retail achieved significant penetration, whereas India’s simultaneous retail modernization and brand vacuum creates the conditions for retailers to pre-empt manufacturer consolidation entirely.

As organized retail continues to grow, the companies controlling the shelves will decide whether growth flows to the new brands they own or the old brands they stock. The trade-offs are significant. Pushing store brands too hard risks losing shoppers, but not pushing them hard enough leaves profits on the table.

Investors and analysts are watching key signals to see if the retailers succeed. First, if Reliance’s RCPL becomes a true brand, its revenue from its own stores should paradoxically fall as it wins on the shelves of its rivals. Second, its cost structure must start to resemble that of its FMCG competitors. Third, the significant price gap between store brands and national brands must remain.

In India’s fast-growing formalizing economy, the gatekeepers of distribution are becoming the new kingmakers, deciding not just which brands survive, but which ones need to exist at all. The question is whether shoppers will ultimately reward the builder of brands or the builder of the cheapest basket.

solid post Manish. thank you

Great post, Manish!