The Silence of the Classics

Saregama, India's oldest music label, missed the 1990s. Now it's paying to catch up.

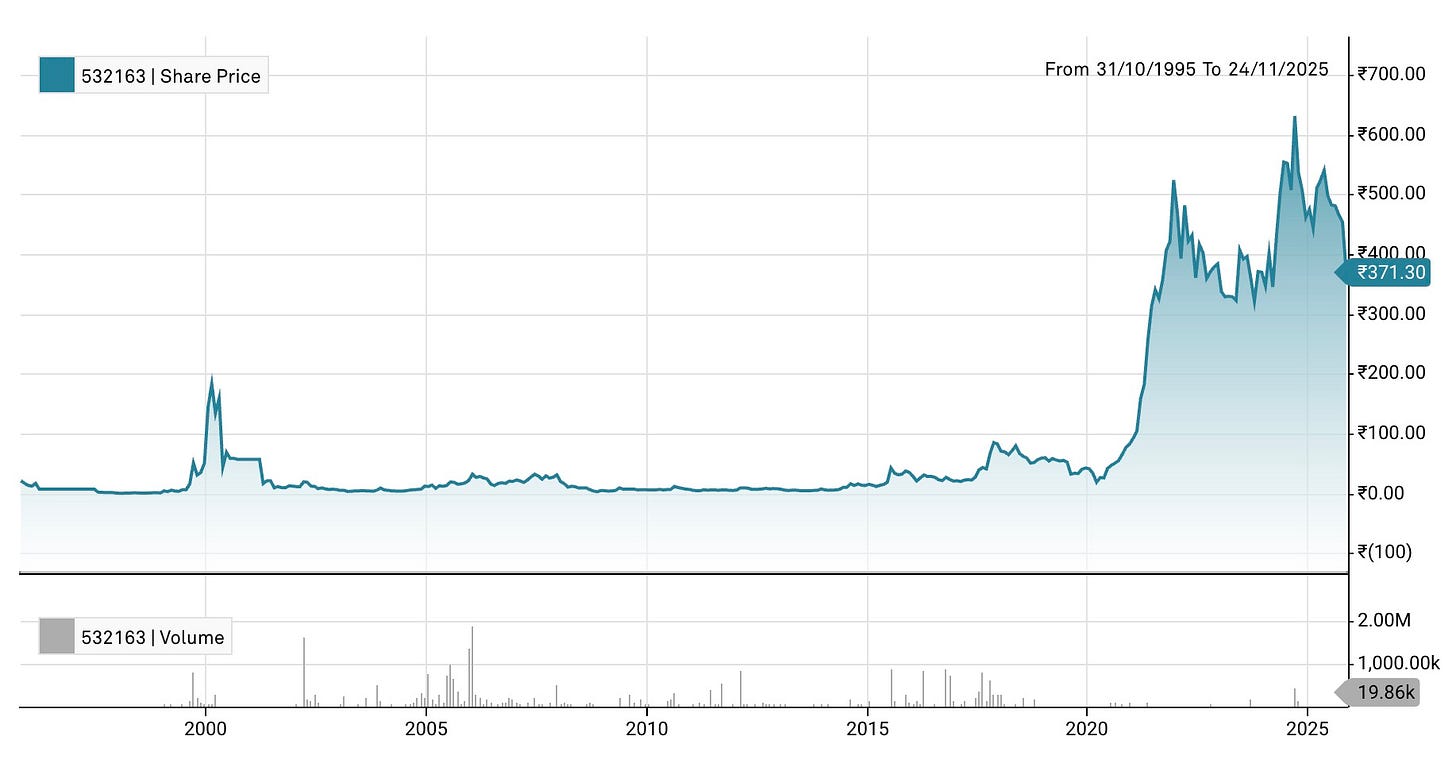

Saregama India traces its origins to early 1900s, when the Gramophone Company established the first recording operation on the subcontinent. The label that would become HMV India signed Lata Mangeshkar, Kishore Kumar, R.D. Burman and Mohammed Rafi, artists whose recordings defined Bollywood for half a century. When investors look at Saregama today, they see more than 160,000 songs, a stock price that has surged wildly in recent years, and a business finally reaping rewards from intellectual property accumulated over generations.

The problem is that most of that IP comes from the wrong generations. Saregama owns one of the most storied music catalogues in the world – but very few songs that Indians actually stream.

The firm’s catalogue runs deep into the 1940s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s – decades when HMV was the only serious music label in India and captured virtually everything worth capturing. But the catalogue thins out dramatically in the 1990s and 2000s, the precise decades when Bollywood music became the streaming-era gold that platforms and listeners actually want. Saregama drifted away from content acquisition during those years, distracted by other ventures, and let T-Series and Tips and Venus hoover up the film music that a generation of Indians now in their twenties and thirties grew up on.

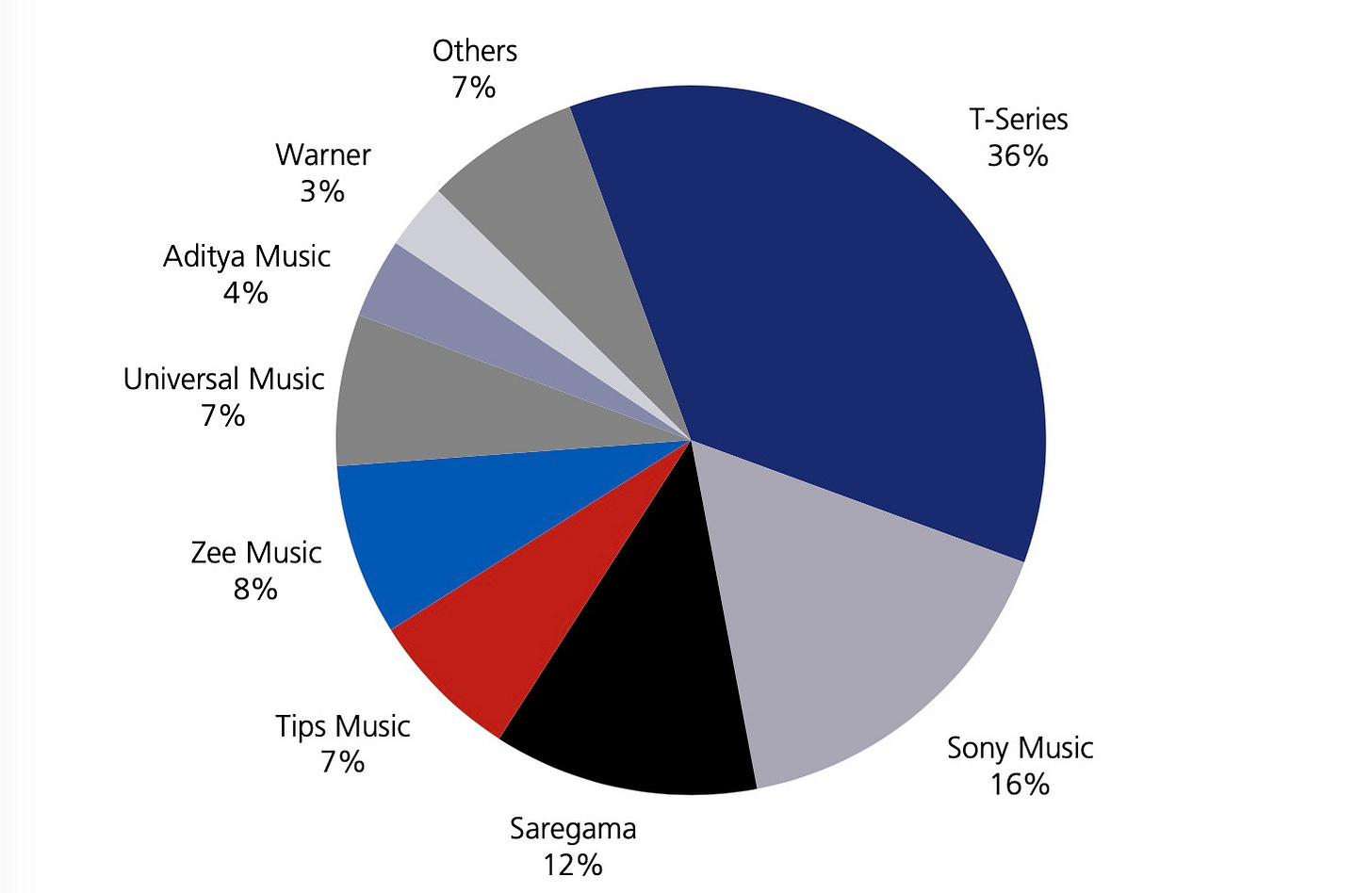

T-Series won that battle decisively. The label now controls 36% of India’s organized music market with a 200,000-song catalogue built largely on 1990s and 2000s Bollywood hits. Saregama manages just 12%.

Now Saregama is trying to fix that gap, but the market itself is cracking. The Indian music streaming market contracted 2% in 2024 after years of growth, shaken by the shutdown of Wynk and Resso and the decision by Spotify and JioSaavn to stop offering minimum guarantee deals to labels. Music companies that relied on upfront payments now face variable payouts tied to streaming performance. For Saregama, trying to build a new catalogue just as the revenue model shifts, the margin for error has narrowed considerably.

About 60 to 70% of streaming revenue for Indian music labels comes from catalogue, and the catalogue that streams is the 1990s, according to industry executives. One executive estimated his label earns 75% of revenue from recent-ish releases and only 25% from back catalogue.

The vintage stuff doesn’t stream the way you’d think. Saregama has monetised it cleverly through Carvaan, a retro portable speaker loaded with old Hindi songs that sells in appliance stores and has become a genuine hit product. Sync licensing for period films brings in serious money – over $200,000 for a 30-second clip is not unusual. But these are niche revenue streams when the main event is streaming, and streaming rewards the songs people put on repeat while commuting or cooking or working out.

The problem runs deeper than just missing the right decades. Saregama doesn’t own video rights for most of its pre-2000 catalogue, which matters enormously when YouTube accounts for half of all streaming revenue in India. T-Series runs one of the largest YouTube channels in the world. Competitors like Tips Music, which own video rights for their entire catalogue, pull in roughly 50% of their digital revenue from YouTube alone. Saregama manages only about 35%.

So the company is spending aggressively to build a new catalogue from scratch – or rather, to buy one. In recent years, Saregama has signed exclusive deals with film production houses, acquired a new-age storyteller, bought regional labels like NAV Records (thousands of Haryanvi tracks backed by the legendary Sonotek), locked up independent artists on 360-degree contracts and pushed hard into Telugu, Tamil, Punjabi and Bhojpuri.

The catch is that content acquisition in Indian music is a miserable business. If you buy the music rights to ten Bollywood films, one or two tend to recoup within a year. Another two or three break even in three to five years. The rest take six years or longer, bleeding slowly into profitability through the “long tail” of catalogue streaming that never quite stops, people familiar with the situation say. Labels try to hedge by pre-selling 50 to 60% of the acquisition cost through licensing deals before they even buy, but that still leaves 30 to 40% riding on whether the songs become hits.

Saregama depends almost entirely on third-party producers for new film music – the most valuable and hardest to acquire content in India. Tips Music, by contrast, has guaranteed access to roughly 35% of its content pipeline through Tips Films, a promoter-linked entity, another 30% through direct collaboration with independent artists, leaving only 35% exposed to the brutal auction dynamics of the open market, according to JM Financial. When content costs are rising and quality content is scarce, guaranteed access matters. Tips Music committed to investing 25-30% of annual revenue in new content acquisition precisely to avoid losing relevance in a market that moves quickly.

Then there is the issue with accounting. Saregama capitalizes content costs and amortizes them over ten years, which smooths reported earnings but masks the underlying cash drain. The approach creates a balance sheet weighed down by unamortized content that may or may not pay off. Tips Music expenses content costs immediately – 100% in the quarter of release. The more conservative approach produces cleaner books but demands stronger cash generation to keep the content engine running.

Revenue concentration makes the stakes even more punishing. A single chartbuster can add 5 to 7% to a label’s annual revenue. A chartbuster album — multiple hits from one movie — can swing revenue by 15 to 20%. So if you miss a year of hits, the whole P&L tends to suffer, and hit-making is getting harder. Five years ago there were more chartbusters; today the industry produces fewer breakout songs even as it releases more music than ever.

Saregama has tried to build moats beyond just owning songs. The company now manages artists directly, signing them to contracts that cover recordings, live performances, brand endorsements and career development. The pitch to talent is access to film placements — still the ultimate aspiration for Indian musicians — and the infrastructure to handle everything from legal work to PR to tour logistics. Other labels outsource live events to agencies; Saregama keeps it all in-house on the logic that whoever controls show bookings controls artist loyalty.

Live events themselves run on 6 to 9% margins, barely worth doing as a standalone business. Saregama does them anyway because working with an artist like Diljit Dosanjh on a national tour cements the relationship, generates PR and creates slots for up-and-coming Saregama artists to open. Diljit tours internationally in markets where Universal and Warner dominate, but he works with Saregama because of relationships built over years.

None of this changes the underlying streaming economics in India, of course, which remain stubbornly ad-supported. Insiders estimate that 80% of label revenue from digital platforms comes from advertising, only 15 to 20% from subscriptions. YouTube alone accounts for 50 to 60% of total streaming revenue; Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, Saavn and Gaana split the rest. YouTube Music and Spotify have about 8 to 10 million paid subscribers each, according to industry insiders.

To be sure, labels have protected themselves through minimum guarantees. When Saregama licenses its catalogue to Spotify or YouTube, the platform pays upfront for two or three years of streaming, covering both free and paid tiers. If actual streaming exceeds the guarantee, Saregama gets more; if it falls short, the guarantee holds. India’s failure to convert listeners into subscribers becomes mostly Spotify’s problem, not Saregama’s. But even these deals are disappearing as platforms reassert leverage.

What Saregama cannot escape is the long payback on its acquisition spree. The company is buying content now that won’t generate meaningful catalogue revenue until the early 2030s at best. The bet is that Indians in 2032 will stream the hits of 2025 the way Indians today stream the hits of 1995-2010. Saregama missed one catalogue cycle and is spending heavily to catch the next one. Whether it works depends on hit rates that nobody can forecast, on artist relationships that must be maintained for years, on regional markets that are growing but remain fragmented, and on an Indian consumer who has never shown much willingness to pay for music.

The company’s famous old catalogue — Rafi, Lata, Kishore, R.D. Burman — is a heritage asset that earns its keep through hardware products and sync deals. The streaming future appears to belong to whoever owns the right songs from the right decades. Saregama is still buying its ticket, and the seats are getting expensive.

What a marvellous post. As a bitter and old ex-music reviewer for BBC In India (and an indian music tragic), I loved the analysis and the take aways. Thank you for this. I wonder what your take is on Universal taking excel share and Saregama taking on a share in Sanjay's

Very insightful!! Thank you