The Key-Man Risk Threatening To Fracture India's Mutual Fund Giants

Three managers hold majority stakes in trillion-rupee portfolios

India's mutual-fund industry looks like a $600 billion fortress of household savings, yet its walls are thin. At the five largest houses, the three busiest portfolio managers oversee roughly three-quarters of all actively managed equity money. In several firms a single individual guides close to half. One exit or illness could shake performance, spook inflows and gouge fee income now priced at more than 35 times forward earnings.

The pay structure helps to explain why the pillar may crack. Total compensation absorbs only 4-7 basis points of assets – about $70 a year for every $100,000 entrusted. The stock-pickers themselves get well under one basis point even though assets have grown 17–21% a year for a decade, while salary costs rose only 13%. This translates to portfolio managers who generate billions in AUM receiving compensation often amounting to just 0.2-0.5 basis points – a fraction of what they could earn elsewhere.

Operating leverage has flowed to shareholders, not to the staff who produce returns. New regulations since 2021 have intensified frustrations – senior employees must lock part of each bonus into the funds they run and endure mandatory lock-up periods, creating a double whammy of delayed gratification that veterans see as yet another obstacle to timely compensation.

Managers who are getting tired of the maths, setting up an independent shop is no longer a pipe dream. Bernstein estimates a private portfolio-management service or alternative-investment fund breaks even at about $350 million of assets. Such vehicles can levy "2-and-20" fees under lighter oversight. Private-bank distributors, hungry for new products, will gladly help big names cross that threshold. Any high-profile departure forces the parent firm to sweeten pay or accept weaker performance, though most analyst models still assume staff costs stay flat in basis-point terms.

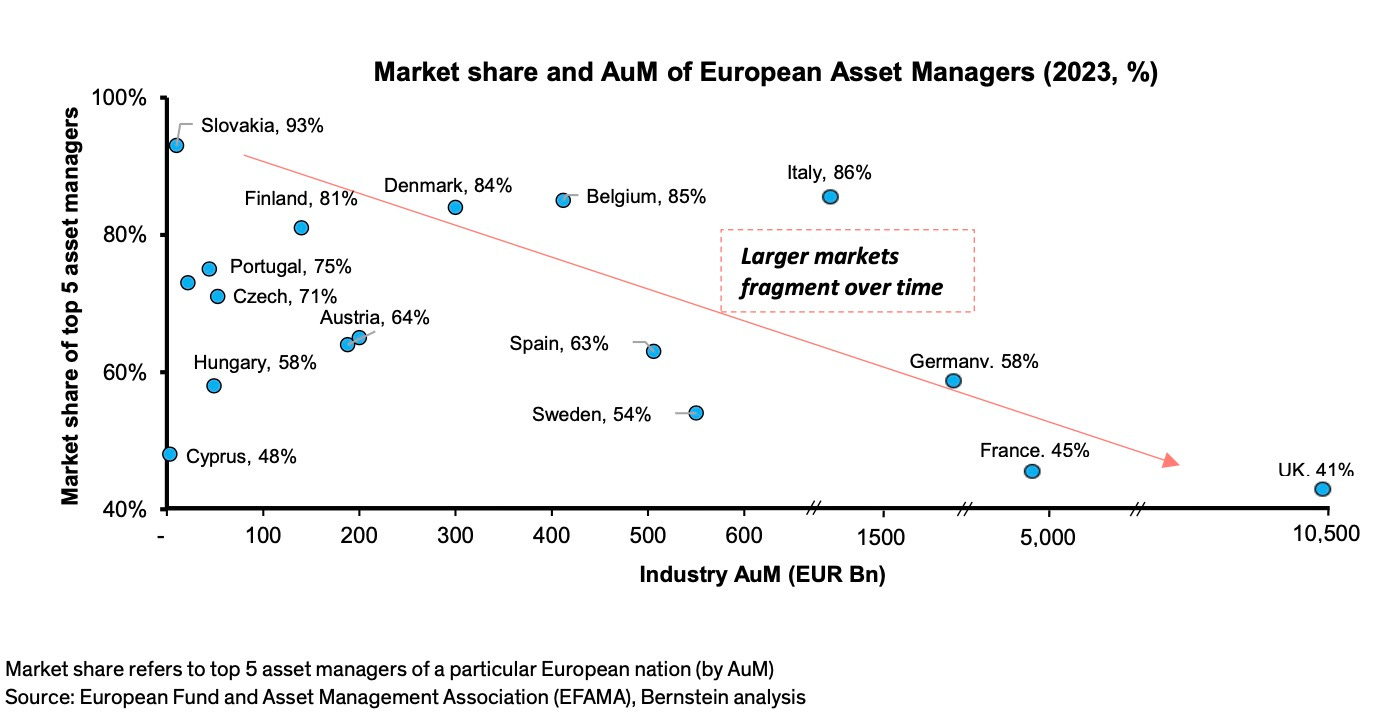

While this all might look like a hypothetical case, history offers an uncomfortable precedent. In Britain, the top five firms now hold 41% of assets, down from shares that once matched India's current 56%. This fragmentation pattern is consistent across mature markets – Bernstein data shows that as markets grow, the dominance of top players invariably diminishes as talent breaks away and establishes boutiques.

Even if every marquee manager stays put, the industry's reflex to remain almost fully invested – bolstered by minimal cash buffers and relentless peer-benchmarking – can still turn ordinary market ripples into outsized waves that sweep every fund along in unison.

Most retail cash enters via systematic plans. Funds hold token cash, so every fresh dollar goes straight into equities. Managers prefer buying an overheated small-cap to lagging peers. As a recent Bernstein note puts it, "you don't get blamed if your fund falls ten percent when the benchmark and peers also fall ten percent." The forced-buyer engine lifts momentum in bulls and can quicken any descent.

Boards see the risks. They are adding co-managers, widening stock-option pools and building databases so investment theses outlive staff turnover. These measures help, but richer equity grants still flow through the P&L and erode the margins investors prize.