The Case For and Against Rapido's Entry To Food Delivery

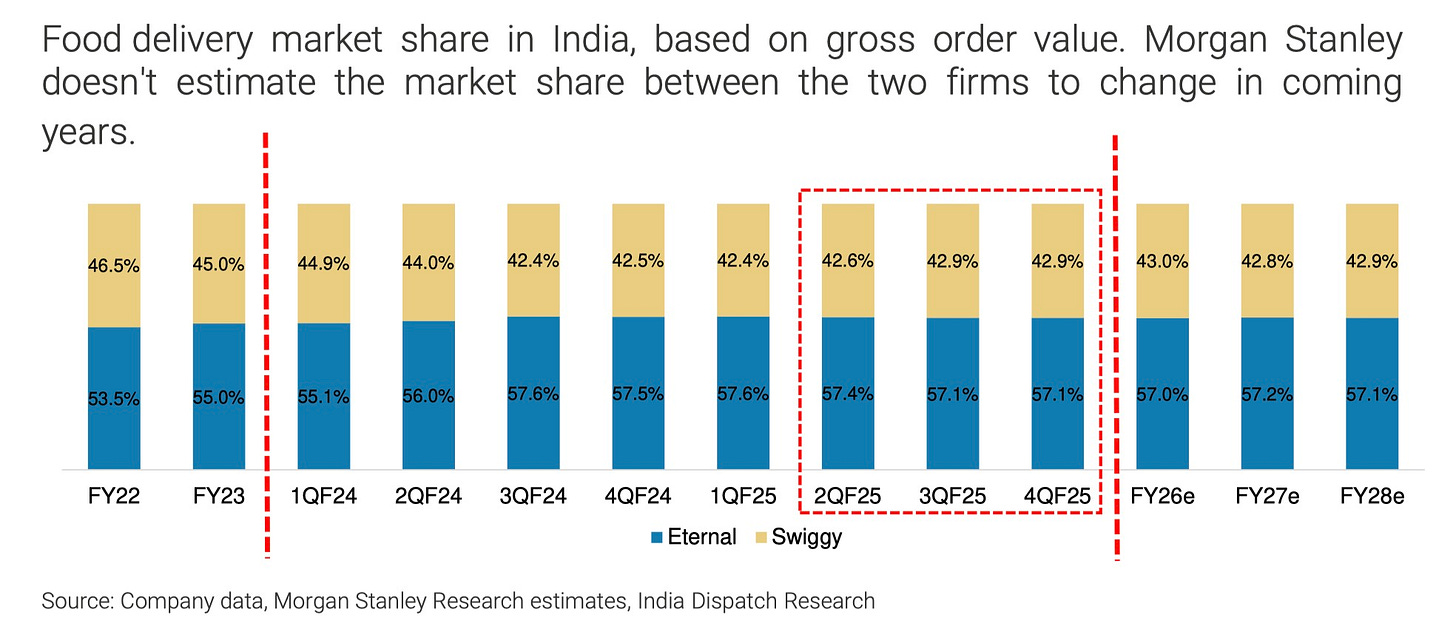

So just last week, I made a case for why I believe that India's food-delivery market, currently a duopoly between Zomato (Eternal) and Swiggy, is unlikely to see any material competition from a third player.

In China, a third player (JD.com) is increasingly making inroads in the food delivery space, which prompted the comparison. But I argued that neither Rapido nor Zepto are in a position to undertake a opex-heavy business like food delivery because their existing core businesses aren't generating cash flow – and won't for the foreseeable future.

Building a food delivery network requires not just hundreds of millions of dollars in the short term, but billions over the long haul to create the infrastructure, negotiate with restaurants, and most importantly, subsidize customer acquisition.

In the current market environment, the argument goes, it's even less likely that either of them will be able to convince investors to give them that kind of capital to fight two well-capitalized publicly listed rivals who've already spent years and billions of dollars cementing their positions.

I haven't changed my view, but ride-hailing startup Rapido's announcement this week that it is entering the food delivery business with a pilot launch in Bengaluru is just too interesting to not talk about. Because here's the thing – Rapido actually has a very compelling story.

Rapido has always been a very interesting case. Swiggy owns more than 12% stake in the firm. Prosus, Swiggy's largest shareholder, is also an investor in Rapido. At least as of nine months ago, Rapido and Swiggy also maintained a very close relationship. So close, in fact, that Swiggy has weighed acquiring a majority stake in Rapido multiple times over the years, according to a person with direct knowledge of the matter.

This relationship goes beyond just equity stakes. Swiggy has also used Rapido's excess, two-wheeler delivery fleet to do some of its own deliveries. In other words, Rapido is no stranger to the food delivery ecosystem and already has a few pieces it needs to potentially get a jumpstart. It understands the operational complexities, the routing algorithms, and most importantly, they have the riders – over 3 million of them.

There are some other factors, too, in Rapido's favor.

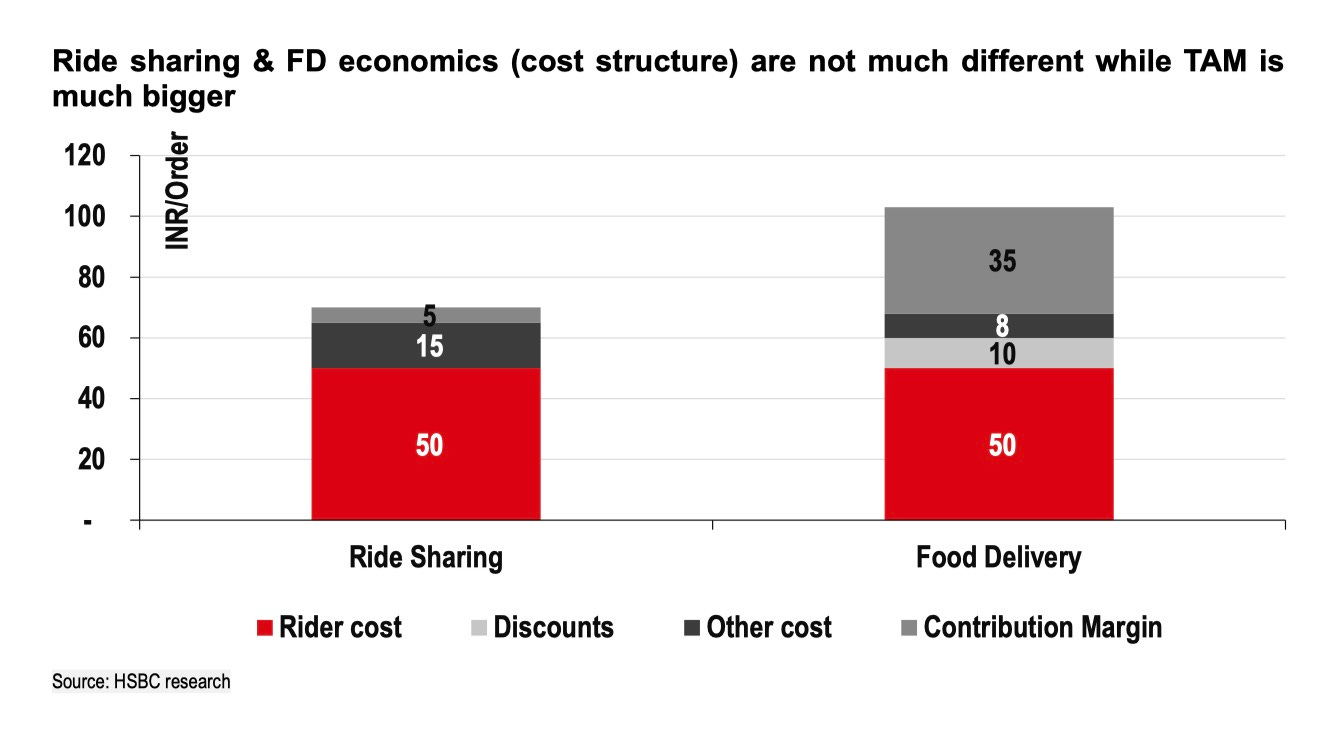

The average two-wheeler ride-sharing cost economics are remarkably similar to those of food delivery, HSBC said in a note Wednesday. The average order value for a two-wheeler ride is around 70 rupees (82 cents), with total variable costs hitting about 65 rupees when you factor in rider costs, discounts, and other operational expenses. That leaves a contribution margin of just 3-4 rupees per ride.

Food delivery, despite all its complexities, actually generates better unit economics. The revenue per order for established players hovers around 100 rupees or more, while the delivery costs – the biggest chunk of expenses – aren't materially different from ride-sharing. We're talking about 50-60 rupees for the average food delivery, including rider costs, discounts, gateway charges, and customer support. The contribution margins? Around 35 rupees per order for the incumbents.

So the bull case: Rapido can leverage its existing fleet of riders during their downtime, operate at much lower margins initially (or even at breakeven), and potentially offer restaurants take rates of 8-15% compared to the 18-20% that Zomato and Swiggy currently charge. For restaurants already squeezed by high commissions – and remember, food delivery prices are already 30-35% higher than dine-in prices – this could be compelling.

Now, the bear case.

First, the restaurant network. Zomato works with over 314,000 restaurants, while Swiggy has partnered with around 252,000. These numbers represent years of relationship building, negotiation, and most importantly, the creation of a consumer habit. When someone opens a food delivery app, they expect to find their favorite restaurants.

Second, customer experience isn't just about getting food from point A to point B. It's about the app interface, the recommendation engine, handling complaints, managing refunds, ensuring food quality standards, and a dozen other things that incumbents have spent years perfecting.

ONDC, which has cracked the mobility space, has been trying to disrupt the food delivery duopoly for two years now with a similar promise of lower commissions but hasn't made a dent because the customer experience just isn't there.

Third, profitability at scale remains elusive even for the incumbents. Zomato, delivering 2.6 million orders daily, manages just 4.4% EBITDA margins. The path to profitability in food delivery isn't about operating at lower take rates; it's about achieving massive scale while maintaining those rates. Rapido's strategy of starting with 8-15% take rates might attract some restaurants initially, but it's a recipe for perpetual losses unless they eventually raise rates – at which point, what's their differentiation?

There's also the question of market expansion versus market share capture. One view in the market is that Rapido could expand the market by bringing in lower average order value restaurants from Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities – establishments that haven't been economical for Zomato or Swiggy to onboard. These could be your local street food vendors or small family-run eateries that can't afford the current commission structure.

Sure, but even if Rapido successfully captures this "tail" of the market, it's worth asking: is this tail profitable? The economics of food delivery get worse, not better, with lower order values and less dense delivery networks. You still need to pay the rider roughly the same amount whether they're delivering a 200-rupee meal or a 500-rupee meal.

I think Rapido's entry is fascinating because it's not coming from a position of pure disruption – they have genuine operational expertise and a nuanced understanding of the market. They might even carve out a niche, particularly in underserved segments or as a lower-cost alternative for price-sensitive consumers.

But disrupting a duopoly is a different game altogether. The incumbents have scale, brand recognition, restaurant relationships, and most importantly, they're already public companies with access to capital markets. They can afford to defend their turf aggressively if needed.

And maybe Rapido doesn't want all of that. Rapido's food delivery venture might actually be more about increasing utilization of their rider fleet and creating operational synergies with their core business rather than a serious attempt to become the third major player. And maybe that's enough. Maybe in a market as large and diverse as India, there's room for a focused, niche player that doesn't need to win the whole game to be successful.

Even though the cons of Rapido getting into the delivery business sound authentic, we should remember that slow and steady always wins the race. If Zomato and Swiggy have decades of experience, Rapido can learn from their mistakes and be agile with its approach to market entry and sustenance.