Why India's Food and Quick Commerce Might Escape China's Perpetual Disruption Spiral

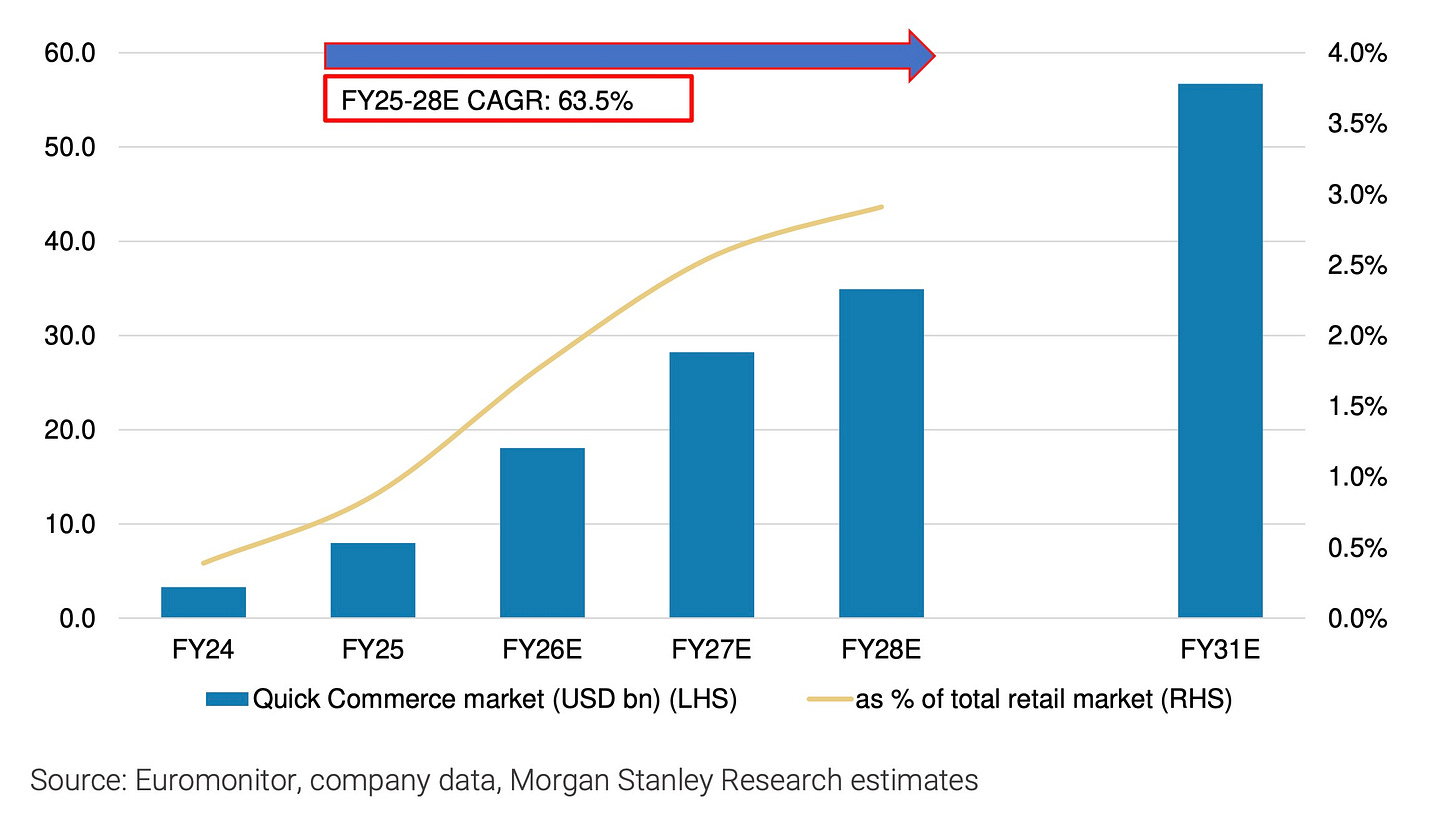

Morgan Stanley raises India's quick commerce TAM forecast to $57 billion by 2030, up from previous $42 billion estimate

Morgan Stanley just raised its India quick commerce market estimate (TAM) to $57 billion by 2030, up from $42 billion previously. The revision comes with an intriguing argument about why India won’t experience the competitive chaos that is reshaping China’s food delivery space.

Morgan Stanley doesn’t elaborate on what happened in China, but here’s what it’s alluding to: JD.com’s recent arrival in food delivery in China has disrupted the long-stable Meituan-Ele.me duopoly. JD achieved this by leveraging its e-commerce profits to subsidize aggressive market share gains.

The strategy worked because JD could treat food delivery as a customer acquisition channel rather than a standalone profit center. Restaurants frustrated with high commission rates, riders wanting better benefits, and customers annoyed with fees all provided openings that JD exploited with deeper pockets.

JD.com is now handling close to 20 million food orders daily, already about a fifth of Meituan’s 2024 peak of about 98 million, demonstrating how rapidly a well-capitalized third player can penetrate what analysts long-considered an impenetrable duopoly.

The Chinese food-delivery structure mirrors those in India, where Zomato has 58% of the market, compared with Swiggy’s 34% share.

Some of the issues that prompted the restaurants and other ecosystem participants to embrace JD.com with open arms hold true in India as well. But the rest of the cards are missing, I believe.

The most obvious potential disruptors like ride-hailing platform Rapido and quick commerce player Zepto don’t have massive adjacent businesses generating the necessary cash flows. This creates a fundamentally more stable competitive structure where rational economics rather than cross-subsidization determines market behavior.

Morgan Stanley makes a slightly different case:

We note that, in India, large horizontal e-commerce players have already tried entering the food delivery space – and then eventually decided to exit without much success. There are new entrants in the form of online cab ride companies, and offline-to-online companies that are trying to enter this space and disrupt business models of aggregators. Technically speaking, risk of competition increases when a segment starts generating profits, thereby attracting more new players. However, in this case, we believe the food delivery/QC companies have stronger balance sheets, better cost structure, and strong network effect in place already – enabling them to defend against new competition, and perhaps even thwart any efforts to scale-up from such would-be competitors. In fact, the perceived risk of Open Network for Digital Commerce (“ONDC,” a government initiative) opening up the competitive landscape in food delivery (as it lowers entry barriers) has not played out – providing confidence in the business model of aggregator companies, such as Swiggy.

China, despite its more advanced digital economy, actually lags India in quick commerce penetration. While India’s quick commerce has crossed 10% of total e-commerce volumes, China’s adoption rates remain lower. Chinese consumers apparently haven’t shifted their behavior as quickly toward instant delivery, possibly because they already have well-developed modern retail and traditional e-commerce infrastructure.

This divergence suggests India’s quick commerce boom might be filling genuine infrastructure gaps rather than offering marginal convenience improvements. Chinese platforms are simultaneously demonstrating market maturation by increasingly looking abroad for growth. Companies like Trip.com and Didi find international expansion essential as domestic growth rates decelerate.

Morgan Stanley expects the quick commerce market to grow at a 63% compound annual growth rate through 2028, with Swiggy maintaining around 22% market share against Blinkit’s dominance.

The unit economics comparison shows both markets targeting similar EBITDA margins of 4-5% of gross merchandise value for food delivery. But the paths differ significantly. China’s competitive intensity forces platforms to constantly defend market share through subsidies. India’s players can theoretically focus more on operational efficiency, though this advantage depends on competitive stability persisting.

Morgan Stanley expects Swiggy’s food delivery business to reach 4.8% EBITDA margins by 2028, while Zomato targets slightly higher at 6%. The gap reflects cost structure differences, but both companies are moving toward profitability rather than engaging in the kind of prolonged subsidy wars that characterize China’s market. In quick commerce, however, the margin expectations are more modest, with Swiggy projected to achieve just 2.6% steady-state margins compared to Blinkit’s 4.7%, highlighting the operational leverage advantages that market leaders typically enjoy.

There’s a regulatory side to it as well, which is comparatively more favorable in India. China’s internet sector has shown how quickly government intervention can reshape competitive dynamics. India’s platforms currently benefit from more predictable policy frameworks, though this may not prove durable as the sector scales.

Things may change, of course. China’s internet market has repeatedly demonstrated that competitive moats built during growth periods can evaporate during economic downturns. The next significant slowdown will test whether India’s quick commerce platforms have genuinely cracked the profitability code or simply benefited from favorable timing and market conditions.