India's Quick-Commerce Boom Built a Very Expensive Speed Trap

The 4,000-store network that was supposed to conquer the subcontinent is discovering brutal economics outside the top cities

The vast and expensive logistics network built for speed by India's quick-commerce sector, once seen as its greatest competitive advantage, is now revealing itself to be a strategic liability. As platforms confront the punishing economics of a nationwide expansion, a dramatic slowdown in the build-out of their core infrastructure is underway. This forced reassessment, a direct consequence of the model’s operational rigidity, sets India’s e-commerce evolution on a unique and challenging path compared to the more flexible and mature models of its global peers.

In Western markets, e-commerce leaders built their dominance on adaptable logistics. In the U.S., giants like Amazon perfected large-scale, centralized fulfillment, while retailers like Walmart successfully use their existing stores as hubs for online orders. In Europe, platforms such as Zalando are evolving into asset-light service providers, with its marketing division showing a 72% EBIT margin. The common thread is infrastructure built for flexible, cost-effective scale.

India’s quick commerce model is a high-stakes wager on a different premise. It is a decentralized network of thousands of small dark stores, each engineered for the singular purpose of speed, serving a small urban radius in under twenty minutes. The pace of this build-out was, until recently, extraordinary; the main platforms now operate a collective network of about 4,000 dark stores, a figure that grew 120% in the nine months leading up to June 2025.

But this frenetic expansion has hit an economic wall. There has been a sharp moderation in store additions in the first quarter of fiscal 2026, according to industry checks. Blinkit’s pace of new stores fell by more than a third compared to the previous quarter, Swiggy Instamart’s dropped by nearly two-thirds, and competitor Zepto’s network actually shrank, according to industry checks and J.P. Morgan. HSBC attributes this slowdown directly to “signs of saturation in top cities” and the “continued unprofitability of the model in smaller towns.”

The Indian quick commerce apps’ pursuit to serve customers beyond the top cities is not only proving to be too expensive, it’s also not making sense. India’s top eight metro cities contribute an overwhelming 83-85% of all quick-commerce sales, according to Redseer. The remaining 92-plus smaller cities, into which so much capital has been deployed, account for just 15-17% of the business. The unit economics in these non-metro areas are deeply challenged. The number of orders per day per dark store plummets from over 1,100 in metros to as low as 350 in smaller towns, where demand often hits a ceiling far below what is needed for profitability.

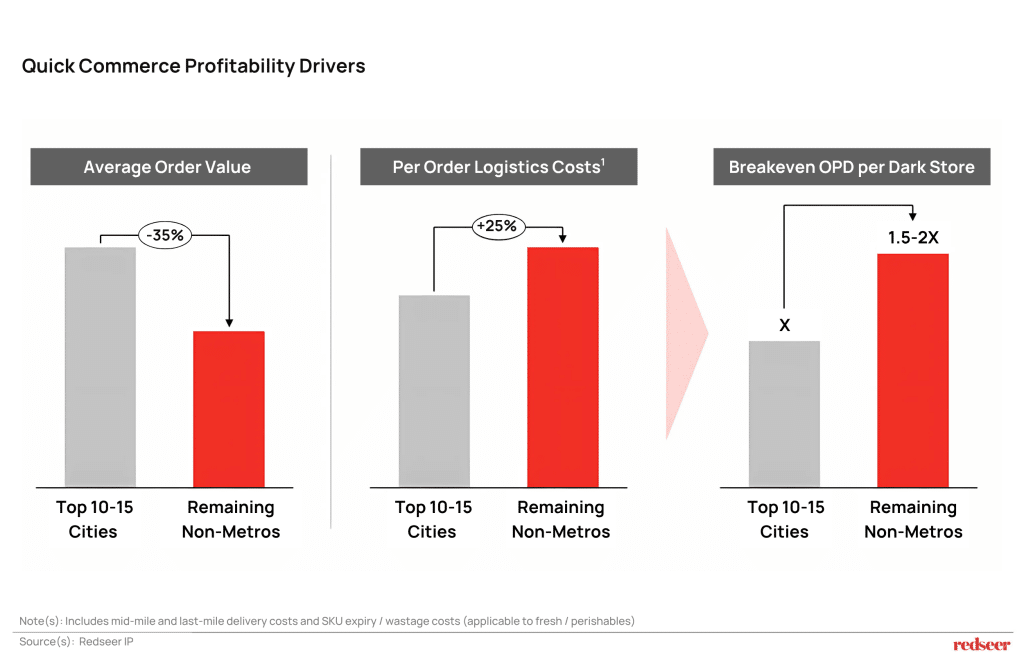

This is because the cost of doing business is higher where demand is weakest. According to Redseer, per-order logistics costs in these smaller cities are 25% higher and average order values are 35% lower than in metros. The punishing result is that the number of orders a dark store needs to process just to break even is 1.5 to 2 times higher. In response, platforms are now experimenting with asset-light “hybrid models,” partnering with local third-party retailers in these challenging areas to expand their reach without the high cost of new dark stores.

At the same time, the core strategy is pivoting to fix the economics. Platforms are shifting from low-margin groceries to higher-value goods to boost order values. Swiggy, for instance, is now focused on expanding its ‘MaxxSaver’ program, which offers larger packs and monthly essentials, and already accounts for over 20% of GMV in its mature cohorts.

This pivot, however, creates a new infrastructural problem. The original dark stores are too small for the new product range, forcing companies to build a second, parallel network of much larger “Megapods”. This expensive duplication adds another layer of cost and complexity. A UBS analysis attributes the near-doubling of Blinkit’s loss per order in the year to March 2025 primarily to these escalating infrastructure costs.

The expansion into these smaller markets also brings a fundamentally different and more challenging consumer into the ecosystem. According to a disclosure from Swiggy, which has expanded its quick commerce offering to more than 100 cities, around 25% of its new quick-commerce users in these emerging geographies are entirely new to the platform, having never even ordered from its core food delivery service before.

This cohort possess poor digital maturity and trust, making them harder to convert into frequent and loyal customers. The implication is that the cost of acquiring and retaining these new users is likely much higher than for their digitally-savvy urban counterparts, adding another layer of economic pressure onto a non-metro model already strained by lower order values and higher delivery expenses.

The infrastructure built for speed has thus revealed its strategic rigidity. The very assets that created the initial advantage have become a liability, ill-suited for the geographic expansion and new product strategies are now being pursued. While the current slowdown in spending is expected to improve profitability from the second half of fiscal 2026, the underlying challenge remains. The model that defined India’s e-commerce boom is now a structural constraint, turning a perceived moat into a millstone that makes the path forward for these companies unlike that of any of their global peers.