Delivering Different Things Entirely

Quick commerce has become a retail-media play in India and a platform weapon in China.

Quick commerce has crashed or sputtered in most markets that tried it. Buyk and Fridge No More shut down in New York. Getir retreated from the U.S., pulled out of Spain, Italy and Portugal and sold its UK operations to Uber. Gorillas collapsed into Getir after burning through capital across Europe. Jokr withdrew from most of Latin America. Zapp went bust in Britain. The model demanded density, frequency and basket sizes that American and European cities could not deliver at unit economics that made sense.

India and China are the only countries where quick commerce is working at scale. Both markets have reached multi-billion-dollar categories. But the business models employed by quick commerce players in either nation have almost nothing to do with each other. India’s version is maturing into a distribution layer that sells attention first and items second. China’s version is functioning as a weapon inside platform wars designed to win sessions rather than profits. In India, some key buyers are brand managers carrying budgets and conversion targets. In China, the buyers are super-app strategists trying to keep users and merchants inside the fortress.

India has built a dense grid of dark stores covering 2-3km catchments and promising 10-15 minute drops. China is leaning more on broad marketplace configurations operating within 30-60 minute windows and mixes dark stores with picking from offline retail locations. The difference in infrastructure is shaping everything that follows.

India’s leaders are compounding logistics scale and then monetising the customer journey upstream. Blinkit currently operates roughly 1,920 dark stores across 210 cities and is on track for a 2,000-store footprint this year. The Eternal-owned firm leads the market at roughly half of all quick commerce GMV in India and tends to price near market medians while leading on SKU availability. The expanding presence is bringing higher net average order value to the firms and letting them moderate headline subsidies.

Quick commerce in India started as a replenishment service with most orders arriving just before breakfast or lunch. Assortment expanded as convenience and instant gratification took hold. India’s QC leaders are now competing to expand assortment, reliability and inventory depth rather than undercutting price at any cost.

By 2030, India’s quick commerce could reach 47% of online retail against China’s 11%, Bank of America projects. This gap does not reflect a difference of taste but of network design, urban cost curves and state of economies.

Take rates (the percentage of GMV that a platform keeps as revenue) run about 15-20% in India versus roughly 10-11% in China. Average order values sit at $6-7 in India against $10-12 in China, according to latest disclosures from the firms. Chinese customers spend nearly twice as much per order yet Chinese platforms still struggle with profitability under subsidy pressure.

India is expected to sustain around 5% steady-state EBITDA as the market rationalises. Platforms are shifting into higher-margin categories and private label. They are negotiating better sourcing terms as scale builds. Assortment expansion lifts basket sizes. Advertising yield adds another layer on top. None of this requires burning cash every quarter.

Analysts at BofA estimate retail-media and related advertising run at about 3-3.5% of GMV today and could rise to 5-5.5% of GMV carrying roughly 90% EBITDA margins. That margin characteristic is creating operating leverage without inviting a price war at checkout. Ad slots, retail-media tools and brand partnerships were impossible in the old kirana distribution stack. At 90% margins this is revenue that pays for reliability rather than just growth.

India’s densification is happening both in top metros and in tail cities, raising service levels without breaking delivery costs. Blinkit is leading the expansion while Zepto and Instamart have slowed store openings, allowing their older locations to mature and improve contribution margins. Competition has already cooled at the edges as Zepto and Instamart balance growth with EBITDA and as newcomers fail to find a wedge. BofA expects consolidation around two or three national winners. Capacity will still expand fast but the centre of gravity will drift toward procurement, private label and ad yield, a recipe for margin recovery as the category gets bigger.

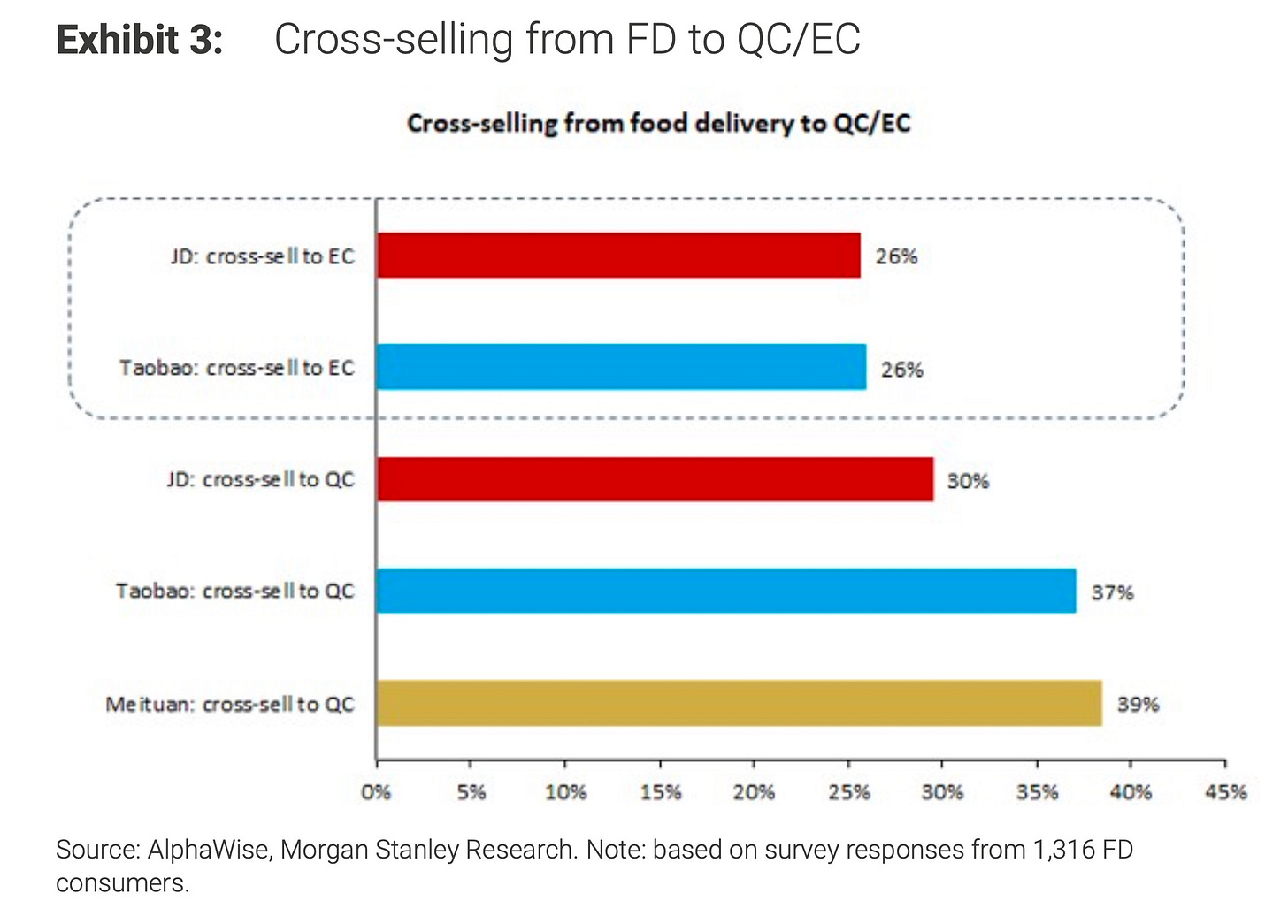

Alibaba and JD currently appear to be treating food delivery and quick commerce in China as a traffic driver rather than a profit driver. The platforms use the channel as a lever to test cross-sell, ROI and ecosystem synergies. Alibaba, JD and Meituan together are ploughing around $21 billion into consumer, rider and merchant subsidies this year. BofA expects the market to reaccelerate to 40% plus growth in 2025 and remain brisk thereafter. Daily orders across food delivery and quick commerce peaked at about 250 million in July, up from roughly 80 million in January.

Regulators in China have pushed back against the subsidy war. Platforms were summoned on May 13 and again on July 18 to hear calls for rational competition and ecosystem health. The State Administration for Market Regulation released draft rules in September focused on fees, promotions, safety and fair competition.

Chinese leading players maintained operating margins of 5-10% in the first quarter of 2025. Meituan’s quick-commerce orders flipped to loss-making from the second quarter as take rates fell and delivery costs rose under subsidy pressure. Meituan’s special delivery and first-party online supermarket arm give it operational advantages. Those advantages are being neutralised at the P&L line by the subsidy war. Management has indicated the long-term target for food delivery and quick commerce is daily orders of 100 million at $0.14 profit per order. That unit profit target sits 30% below the company’s $0.18 operating profit per order in 2024.

About 41% of Chinese quick-commerce orders are incremental rather than cannibalised from existing e-commerce, according to Morgan Stanley. Another 51% substitute offline spend. In a market where user time spent is the currency of competition, that justifies ongoing spend even as unit margins compress. QC buys mindshare that can be monetised elsewhere across the platform, from broader e-commerce to payments and local services, which explains why the cheque books opened.

China’s long-run profit pool in quick commerce probably looks thinner per unit than India’s, though the volume and the ecosystem value can still be large. BofA reckons the segment could approach 10% of online retail over time. Morgan Stanley lifts its 2030 TAM to $352 billion, roughly 12% of online retail, as subsidies train users into the habit. The category will get bigger, probably much bigger, but the margin question will remain subordinate to the share question until the traffic battle resolves.

India’s new entrants to QC should study China’s brutal clarity about what QC is for inside a platform. Morgan Stanley calls the Chinese contest a “burn to earn” 30-minute battle: earn sessions now to earn economics later. That logic helps explain why Alibaba’s $7 billion push forced rivals into matching outlays and why analysts think competitive intensity will peak before it recedes. Indian firms do not need that scale of brinkmanship but they can borrow the idea of using QC to cross-sell into adjacencies where unit margins and cash conversion are better.

China’s platforms could borrow the discipline of pricing near medians rather than at extremes and winning on availability and assortment. That combination lifts net AOV without inviting counter-subsidies. Treating retail-media yield not as window dressing but as an explicit line of defence for contribution margins and a reason to invest in data plumbing and category depth offers another path to taper the subsidy treadmill without surrendering frequency.

India is building a retail-media infrastructure that happens to have logistics attached. China is running a strategic traffic lever that happens to have logistics attached. The former is designed to earn its margins. The latter is designed to earn the right to margins later. Both can be viable, but only one is likely to be peacefully profitable.

For quick delivery to work, you need high density cities, and low cost of labor. NYC was really the only city in the US where the density worked but the cost of labor is too high when you are only delivering convenience items. Even when you're vertically integrated and you can take a margin on the items you're selling.

I'm guessing the cost of labor in India is low and supply of drivers is very high, thus enabling delivery with an AOV of $6-7 in high density cities. And it sounds like Blinkit has built an impressive number of dark stores (2k is no joke!). Not as well versed in China but my guess is that they also have an over-supply of labor (but doubt it's as stark as emerging markets like India/ Latam/etc), and it sounds like the AOV is slightly higher. The other nice thing about convenience items is that they can be batched more effectively than food. Speed matters but the product doesn't deteriorate with time like with food delivery. A burger and fries gets cold with every minute.. Toothpaste not so much.

It's been a while since I have looked into quick delivery in Latam but I believe there are a few companies doing similarly well because of the dynamics I mentioned above.