The Penny Economics Driving Meesho's 5 Million Daily Orders

A $4.5 sari reveals the ruthless arithmetic behind Meesho's assault on India's e-commerce hierarchy

At just $4.5, a modest sari sold on Meesho reveals how India’s e-commerce startup is systematically undercutting the giants through pennies saved.

A sari seller takes home 300 rupees ($3.5) whether they sell on Meesho, Amazon or Flipkart, but the difference is in what they pay: on Meesho, the combined costs for shipping, payment and promotion total only 77 rupees (90 cents) — about half what Amazon charges and one-third of Flipkart’s fees.

This brings the merchant’s cost of doing business down to 20.4% of gross merchandise value, compared to 34-43% on other platforms. This thriftiness works because the typical purchase on Meesho is under $3, a price point that appeals to 85% of its 187 million annual shoppers, most of whom live in India’s smaller cities and towns.

Meesho’s business model demands rigorous cost discipline to support its low-price strategy, which the SoftBank-backed startup has achieved by steadily reducing fulfillment expenses from 77 rupees to approximately 63 per order over the past eighteen months, primarily through its innovative Valmo platform that creates competitive bidding at every stage of the delivery chain — from first-mile pick-ups to line-haul transport to last-mile riders.

Despite the inherent challenges of micro-sized transactions, the startup maintains a contribution margin of 17-20 rupees per order through a streamlined revenue model where advertising placements and shipping fees together generate 82-85 rupees per transaction.

Some of the details in the story have been sourced from a note CLSA prepared after engaging with the Meesho leadership. Most of the details haven’t been previously reported.

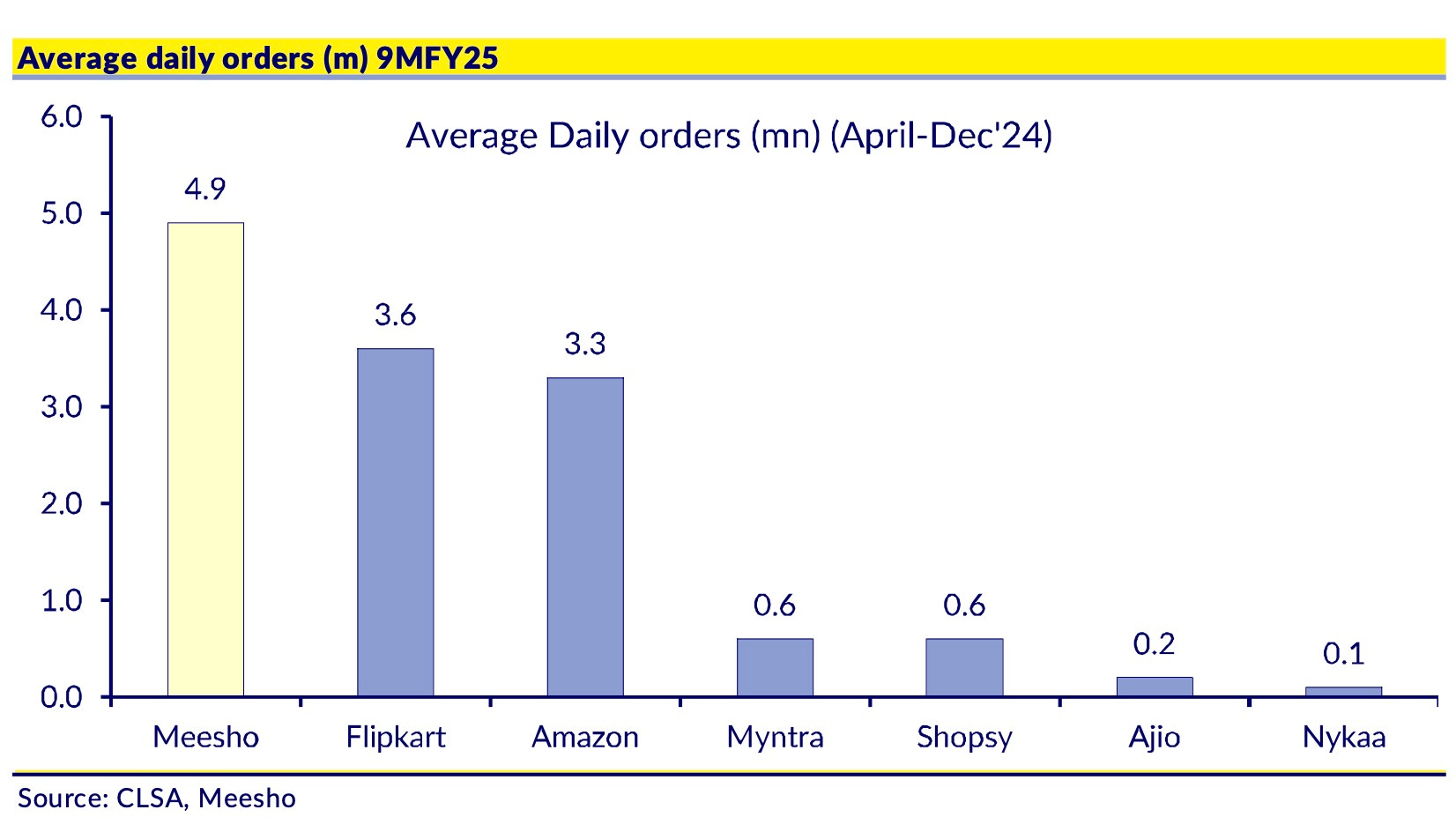

The impressive scale Meesho has achieved stands as both validation of its approach and a critical component of its economic viability, with the platform now handling about 5 million orders daily — surpassing Flipkart by 36% and Amazon by 48% — while demonstrating remarkable capital efficiency by supporting its $6.2 billion run-rate GMV with just $0.7 billion of invested capital.

Although the Bengaluru-based startup commands 37% of India’s e-commerce orders, the small average transaction size means it accounts for only 8-9% of the sector’s total value; nonetheless, this operational model has generated positive cash flow for five consecutive quarters, accumulating $118 million in operating cash.

Meesho’s scale derives not from targeted searching but from creating an engaging browsing experience where shoppers spend nearly 500 seconds per session — approximately 20% longer than on competing sites — scrolling through 14 billion product listings and 59 million pieces of user-created content daily.

This approach has enabled significant diversification beyond the startup’s initial focus, with apparel’s share of orders declining from 63% in 2021 to 35% today as categories like homeware, beauty and baby-care products gain popularity, all while maintaining consistent average order values that underscore the fundamental importance of price discipline to the business model.

For investors, Meesho’s appeal lies in its potential to convert high transaction volumes into increased customer spending over time, with CLSA forecasting sales and revenue growth at 26% annually through fiscal year 2030, gradually increasing the startup’s share of India’s retail e-commerce market from 8.5% to 10% even as the overall sector doubles in size.

The brokerage also projects shipments across India to grow at an even more aggressive 30% annual rate, with tier-2 cities leading this expansion and creating substantial headroom for Meesho’s small-ticket commerce approach in previously underserved markets.

That said, Meesho’s competitive advantage may not be as secure as initial appearances suggest, with CLSA cautioning that if established platforms like Amazon or Flipkart manage to match Meesho’s sub-65 rupees fulfillment cost, the fee gap that currently enables sub-$3 purchases would rapidly diminish. The startup also faces internal challenges as it expands into heavier product categories such as small appliances, which naturally increase handling costs at rates that advertising revenue might struggle to offset.

Without continuous improvements in logistics efficiency, detailed CLSA’s analysis indicates that contribution margins will remain capped below 20 rupees per order — a figure vulnerable to external pressures like rising fuel costs, wage inflation, and potential declines in delivery partners’ willingness to bid aggressively for Valmo volumes.

International comparisons offer both encouraging precedents and cautionary lessons, as similar value-focused platforms like Pinduoduo in China and Shopee in Southeast Asia have successfully employed small-purchase strategies to drive e-commerce adoption and now maintain respectable profit margins. However, both operate in markets where smartphone usage and consumer spending power have developed more rapidly than in India’s economy.

While Meesho’s leadership confidently predicts that Indian retail will follow a similar evolutionary trajectory, the IPO-bound startup remains heavily dependent on the same fundamental drivers that facilitated its initial success — affordable mobile data, cost-effective logistics infrastructure, and a robust ecosystem of independent sellers.

The central question that will determine Meesho’s long-term viability is whether a platform optimized for three-dollar purchases can maintain its structural cost advantages once India’s established retail giants decide that small-ticket commerce deserves their full strategic attention.