Whatever Happened To India's 500 Million Consumers?

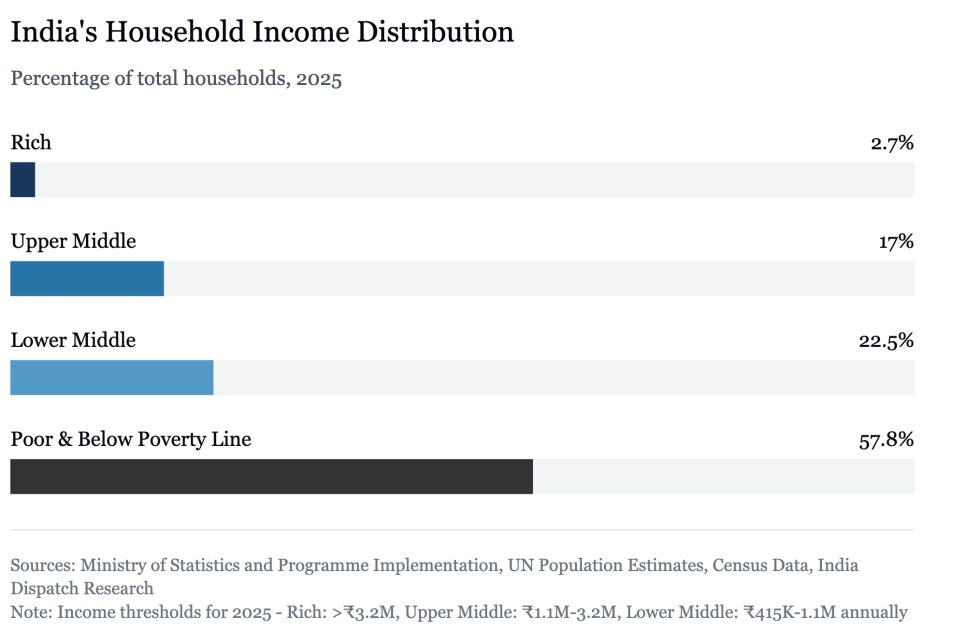

India's widely celebrated middle class, often portrayed as an engine of the world's fifth-largest economy, represents a far smaller segment of the population than commonly believed.

The top 10% of India's population controls 60% of national income, and the top 5% holds 40%, according to a new analysis. Those typically identified as middle class in India actually belong to the economic elite — the top 20% of the income pyramid.

Of India's current 320 million households, only about 64 million — less than 20% — qualify as upper-middle or affluent class. The middle 20% decile of India's population spends less than half of what the group between the 80th and 90th percentile spends.

For global businesses and investors, these findings necessitate a fundamental reassessment. The current market of meaningful consumers numbers closer to 220-230 million people, not the frequently cited half-billion figure.

This concentration becomes more pronounced in savings patterns. While Indian households save approximately $650 billion annually, the top 20% command about 85% of this pool. The lower middle class, despite its larger population, contributes just $120 billion. The poorest segment shows negative savings, depending on government support for sustenance.

The wealth disparity manifests clearly in asset ownership. In rural India, only 3% of households own air conditioners, compared to 17% in urban areas. Water heater ownership stands at 3% and 8% respectively. Even refrigerator penetration reaches only 25% in rural areas and 63% in urban regions.

Financial market participation tells a similar story. Only 13% of Indian households have any exposure to mutual funds. Even among rich households, mutual fund penetration reaches just 50%, dropping to 20% for lower-middle-class households.

The disparity extends to the workplace. About 70% of graduates and 42% of postgraduates work in jobs that don't require their level of education, according to Bernstein. Indians work among the longest hours globally — 46.7 hours per week — while receiving comparatively low monthly wages. Female labor force participation remains at 37%, among the lowest in G20 countries.

The analysis suggests meaningful change is coming, but gradually. By 2035, India's total middle class (both upper and lower) could expand to 190 million households, encompassing about 800 million people, Bernstein estimates. The proportion of households earning over one million rupees annually is projected to increase from current levels of 15% to 38%.

However, this transformation faces significant hurdles. Low-income states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, comprising over 25% of India's population, have per capita power consumption below 1,000 kilowatt-hours — far below the global average of 3,600.

India's path to a broader middle class awaits its transition to upper-middle income status by decade's end, when GDP per capita approaches $5,000. Until then, the consumption story remains predominantly about its economic elite, with the real middle class largely absent from the narrative.