Pricing Out the American Rotation

A $100,000 headfake

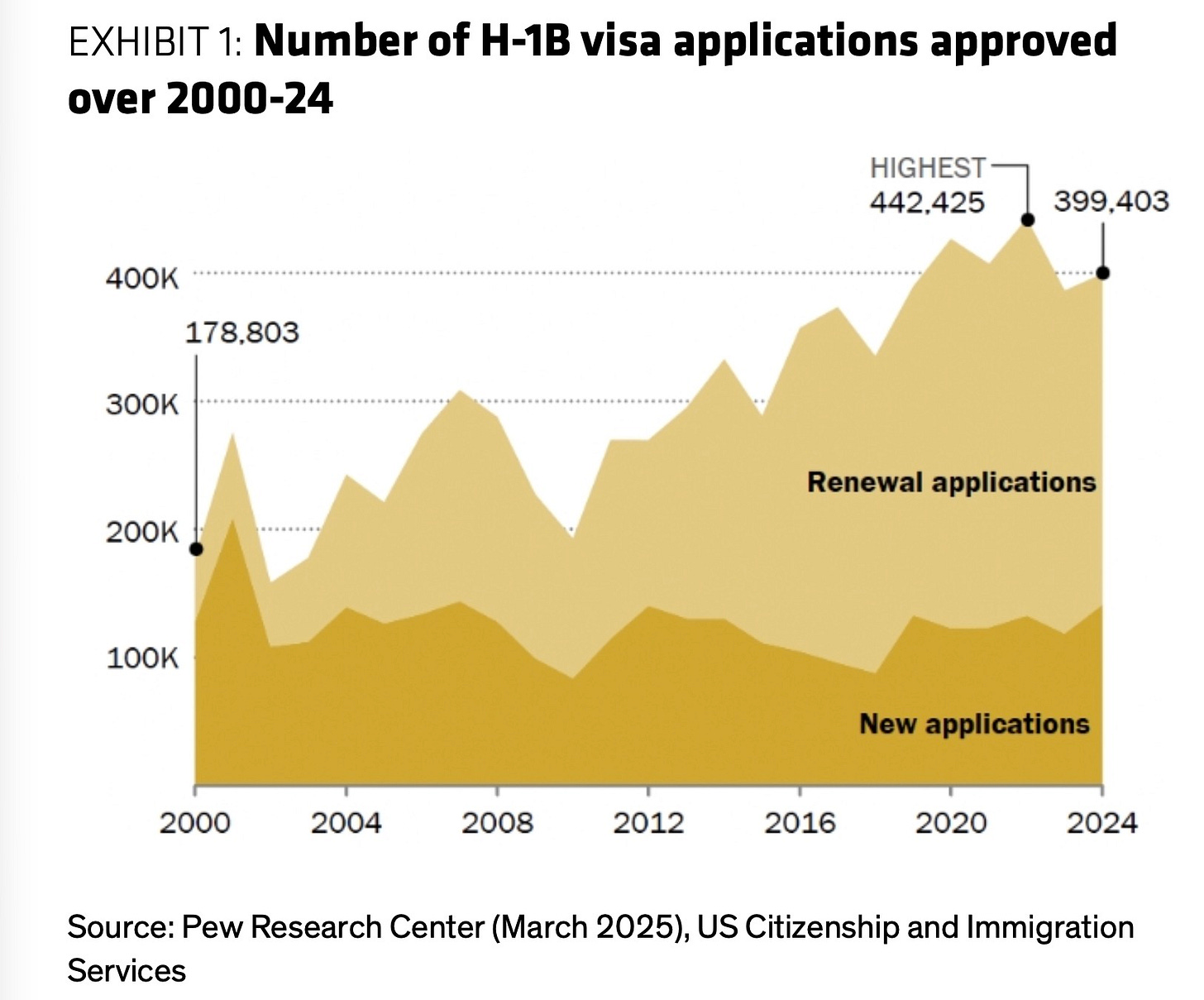

The U.S. will charge companies $100,000 for each new foreign tech worker under an initiative officials call Project Firewall, a move that squarely targets an immigration channel where Indians account for an estimated 70% of all visa holders. The fee becomes effective with the February 2026 visa lottery window and applies to new H-1B petitions, while renewals and current visa holders remain exempt. The proclamation also directs the Department of Labor to begin rulemaking to increase prevailing wage requirements, adding a second, potent layer of cost pressure. Previous visa expenses ranged from $2,000 to $33,000, making the new fee a radical departure from decades of immigration pricing.

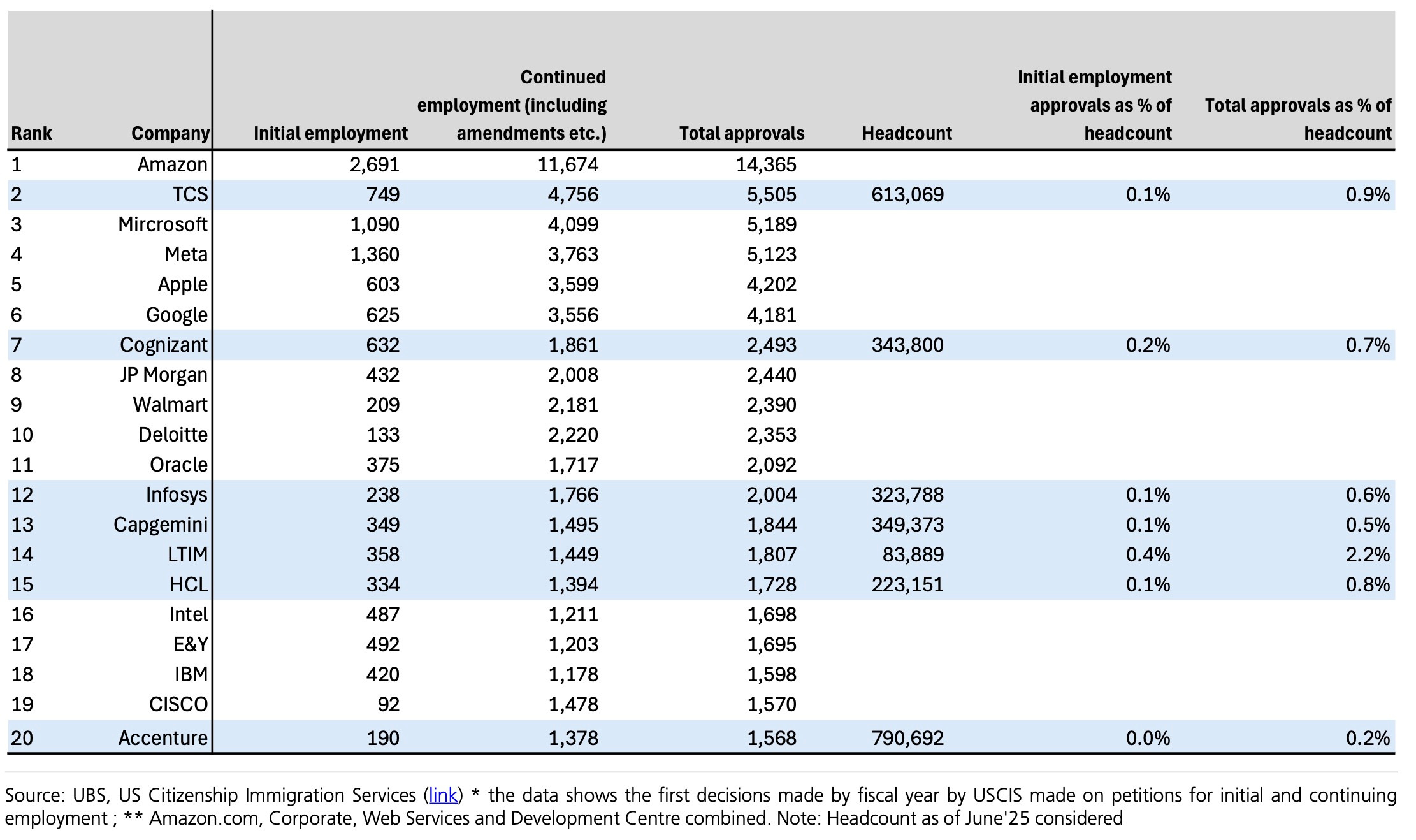

The fee exceeds what many of these engineers earn in a year, with the average H-1B salary at TCS running about $105,000. A typical engineer deployed to an American client site generates $150,000 to $200,000 in annual billings at roughly 10% operating margins, producing $15,000 to $20,000 in yearly profit. The $100,000 upfront fee eliminates five to six years of that entire profit stream. J.P. Morgan states bluntly that the move effectively “prices out the utility of H-1B as a source of labor supply.”

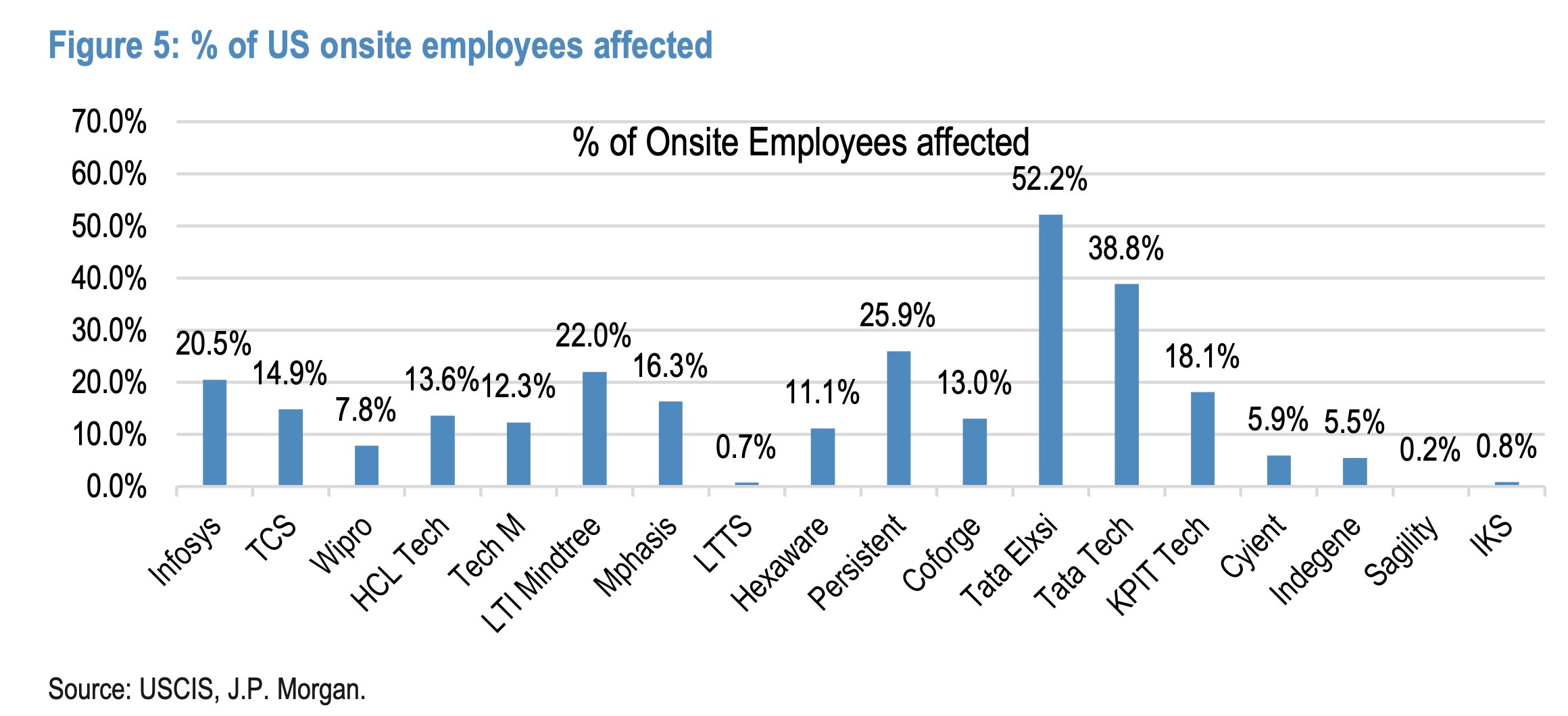

For all their many flaws, you have to concede: Indian IT companies have been preparing for this moment — to an extent. They have already pivoted away from the visa-dependent model, making the new fee less catastrophic than it would have been a decade ago. Combined initial and continuing H-1B approvals now represent only 0.2% to 2.2% of the total workforce at major firms, according to UBS, while new approvals alone account for under 0.4%. The “continuing employment” category inflates even these modest numbers because the same employee can generate multiple approvals when changing client sites or roles — a quirk (PDF) stemming from a 2015 regulatory precedent involving Simeio Solutions.

This reality allows them to accelerate the geographic arbitrage they have pursued for years — routing more work to India, Canada, and Latin America — rather than absorb the fee. Firms can maintain their existing visa holder base while letting normal turnover occur over three to six years, offsetting, per Morgan Stanley’s estimates, roughly 60% of the financial impact through increased offshoring and selective price increases. The net damage to operating profit would stay contained at around 50 basis points, or a 3% to 4% hit to earnings spread across the renewal cycle.

American wage inflation, rather than visa availability, emerges as the real pressure point. A 5% increase in on-site compensation could reduce profits by 4% to 13%, depending on each firm’s U.S. exposure and reliance on subcontractors, according to UBS. Companies that maintain large American workforces or depend heavily on third-party contractors face the steepest impact as local talent becomes scarcer and more expensive.

Contract renegotiations will determine how quickly companies can shift delivery models. Moving a project from on-site to offshore requires rewriting service-level agreements and adjusting security protocols. Revenue growth will likely wobble during this transition as management teams restructure their platforms while navigating a soft macroeconomic environment and potential AI-driven price deflation through 2026 and 2027, Jefferies warns.

European integrators have already demonstrated how the new model will function. Capgemini delivers 80% of its North American work from offshore locations while maintaining a 59% global offshore mix that increases by roughly one percentage point every three to six months. The company maintains competitive margins in North America despite minimal on-site presence, proving clients will accept remote delivery.

American corporations face their own staffing crisis that the new fee will compound. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 357,000 annual IT job openings on average between 2024 and 2033. Corporate technology budgets will absorb higher costs, whether through elevated local wages, premium visa fees passed on by vendors, or increased offshore delivery, guaranteeing expense inflation.

The policy could create an unexpected boost for India’s services export economy. The rational corporate response assumes a higher offshore delivery share, meaning more dollars flow to technology centers in Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Pune. India’s services surplus expands while remittances from workers abroad — a $35 billion annual flow from the U.S. — potentially shrink, strengthening the current account.

Career trajectories within Indian IT companies will reshape. The traditional path of a U.S. rotation after two years becomes available to fewer engineers, replaced by faster progression within Indian offices and more complex projects routed directly to offshore teams. Companies might want to rebuild their talent proposition around technical challenges rather than international exposure.

Political resistance has mobilized. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed formal objections, while technology giants lobby for modifications. The biggest H-1B users will push to soften the policy’s edges, though political pressure cannot eliminate the fundamental shift in delivery economics the fee creates.

Washington’s attempt to protect American tech jobs will likely achieve the opposite by accelerating the offshoring it meant to prevent. Companies will maintain minimal on-site presence while routing everything else to locations where talent costs less and visa fees don’t apply. The $100,000 fee becomes a tax on proximity in a scarce market, pushing work toward time zones rather than pulling workers toward clients.