Hollow at the Base

AI is gutting the entry-level jobs that powered India's technology services boom. The consequences will be felt far beyond its borders.

The foundation of India’s $250 billion technology services industry is a simple bargain. A seemingly endless supply of engineering graduates, earning as little as $5,000 a year, could be trained to perform work that cost ten times as much in the developed world. Giants such as Tata Consultancy Services and Infosys architected their global advantage in part on this labour arbitrage, assembling vast pyramids of junior talent to serve clients from New York to London.

That model, a pillar of India’s current economy, is now facing a structural crisis. AI is methodically eliminating the very entry-level roles that served as the training ground for a generation of programmers and project managers.

This transformation is striking the Indian economy at a particularly notable moment. The IT sector, which employs 5.4 million people and contributes 8% of the country’s GDP, forms the very backbone of urban middle-class employment. Its upheaval coincides with the nation’s pressing need for mass formal employment.

India’s working-age cohort is projected to swell from approximately 980 million in 2024 to more than 1 billion by 2033, adding 8-9 million people to the workforce each year. They will enter a services-heavy economy that accounts for around 64% of Gross Value Added (GVA) and 42% of total employment.

What’s happening now isn’t a cyclical downturn but a fundamental rupture, most visible in the collapse of entry-level hiring. In the 2023 fiscal year, the top four IT exporters hired a combined 225,000 fresh graduates; by fiscal 2024, that figure had plummeted by over 70% to some 60,000.

To put this in perspective, TCS and Infosys combined added over 157,000 employees in the hiring boom of 2022 fiscal year, but that number fell to just 12,771 in 2025 fiscal year.

This hiring freeze is also visible in the overall headcount of the industry’s giants. For the first time in decades, they are shrinking — TCS seeing its workforce fall by over 13,000 in fiscal 2024 and Infosys shedding 25,000.

The driving force behind this disruption is AI, which targets the exact tasks that once served as the industry’s induction schools. Studies by firms like Accenture suggest generative AI could automate 30-40% of the work done by junior software developers and testers. Basic code generation, documentation and quality assurance are increasingly being handed over to AI assistants.

Persistent client demands for lower prices are forcing firms like TCS and Infosys to deliver traditional services with fewer people.

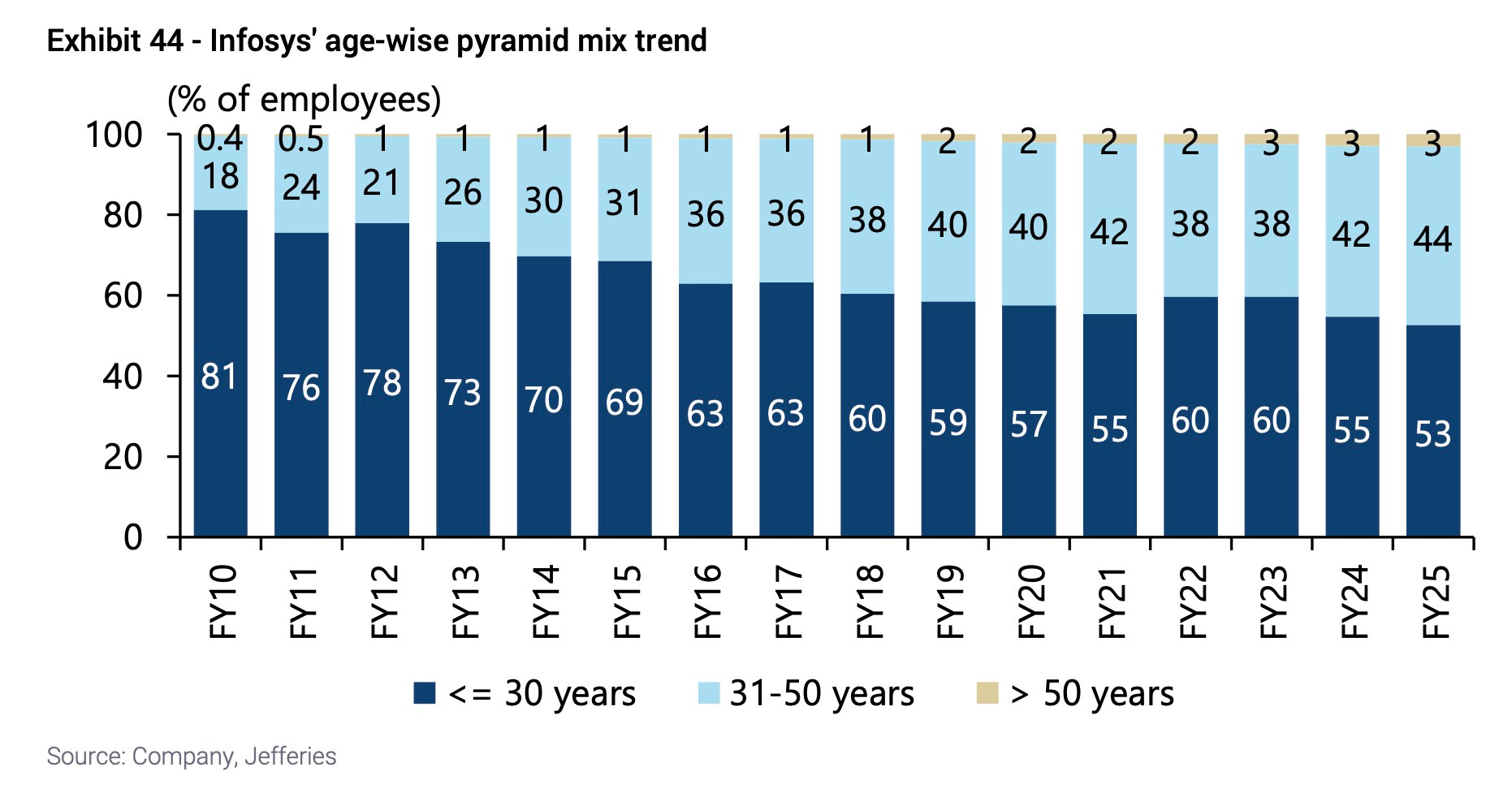

This collapse in junior hiring is accelerating a demographic transformation that has been underway for over a decade, fundamentally altering the age profile of the industry’s workforce. The share of staff under 30 at Infosys plummeted from 81% in 2010 to a projected 53% by fiscal 2025, according to an analysis by Jefferies. Baselines may vary, but the overarching story is consistent: the proportion of junior employees has contracted by roughly one-third in fifteen years.

As recently as 2010-11, corporate disclosures reviewed by India Dispatch showed that 70% of employees at TCS were aged 30 or lower. At the end of fiscal 2025, that mix accounted for less than 48% of its employees in India. This youthful foundation has steadily eroded across the sector; Wipro reported 60% in that bracket by 2015-16, and HCLTech just 39.5% by fiscal 2020.

Even as AI is delivering productivity gains, a corresponding financial windfall for the companies themselves — at least most of the IT giants — is not materializing yet. The economics of the transition defy conventional assumptions about automation, with group EBIT margins projected to remain flat at around 20% through fiscal 2028, per Jefferies. This is largely because higher-margin service lines face intense pricing pressure while the business mix shifts towards higher-cost onshore consulting.

Future growth now appears almost entirely dependent on the expansion of AI-related services, which are forecast to grow at 15% annually but demand senior experts in client locations, not junior coders offshore. The market for non-AI IT services, meanwhile, is projected by Gartner to shrink by 1-3% a year, eroded by a cumulative 20% revenue deflation by 2029.

Nor do other business lines offer a significant refuge. Infrastructure management, for instance, provides only modest new efficiency gains of 5-10%, much of which is already given away in price concessions. In business process outsourcing, while some segments see high automation potential, the risk for Indian firms lies in broad back-office work, where roughly 35% of productivity gains are expected to be passed on to customers over five years.

Confronted by these pressures, leading firms are racing to remodel their businesses by converting internal AI tools into sellable platforms and shifting from pricing by the hour to pricing by outcome. Companies that remain dependent on the old model of labour arbitrage face the prospect of steady margin compression, as the cost advantage held by the IT giants erodes with every task that AI learns to perform offshore.

The consequences of this industry-specific shift have far-reaching macroeconomic implications for India, striking at a core pillar of its social contract. For years, an entry-level IT job was the primary pathway from a mass-market engineering college to middle-class stability. The hollowing out of these roles creates a severe mismatch in the labour market, where the unemployment rate for graduates already exceeds 13%, nearly three times the national average.

A material portion of the 8-9 million people entering the workforce annually is competing for a pool of just 50,000 net new IT jobs projected per year from FY26-28.

India’s policymakers now confront the uncomfortable reality that the sector which once symbolised the country’s ascent no longer functions as a mass employment engine. The alternative requires a massive national pivot towards labour-absorbing sectors such as construction and renewable energy, coupled with a reorientation of education towards AI-complementary skills. Failure risks stranding millions of educated youth between an automated service sector and an underdeveloped manufacturing base.

This Indian predicament also serves as a warning for other emerging economies. The Philippines confronts this in its call centres and Eastern Europe in its nearshoring operations, as automation eliminates the bottom rungs of the professional ladder.

The Indian technology sector may find ways to continue to compete globally, but the architecture that converted inexpensive graduates into middle-class professionals is being dismantled from the bottom up. The pyramid that once represented India’s formidable competitive advantage has become a monument to a model whose time has passed.

Manish -- while I don't disagree with TCS and peers' headcount trends, is there a way we can check net addition of GCC count? EPFO addition is approx 2 Million monthly btw

I’m skeptical that AI has had such a profound impact so soon. LLM based tools may indeed help improve productivity but probably not at the level you are implying.