The Inevitable Shape of Cheap Online Retail

Why value commerce platforms in China, Southeast Asia and India ended up as ad-and-credit businesses disguised as marketplaces.

China, Southeast Asia and India could hardly be more different as markets for online retail. China is an upper-middle-income industrial state where e-commerce has been mainstream for nearly two decades. Southeast Asia sprawls across a stitched-together archipelago of under-banked economies where more than half of retail flows through unbranded channels. India remains poorer still: three-quarters of its retail market is unorganized, e-commerce penetration sits at about 7% and most shopping takes place in tiny outlets where credit cards are virtually unknown.

Geography, income levels and infrastructure suggest these places should have produced radically different answers to how to sell goods online to the masses. They have instead produced nearly identical answers three times.

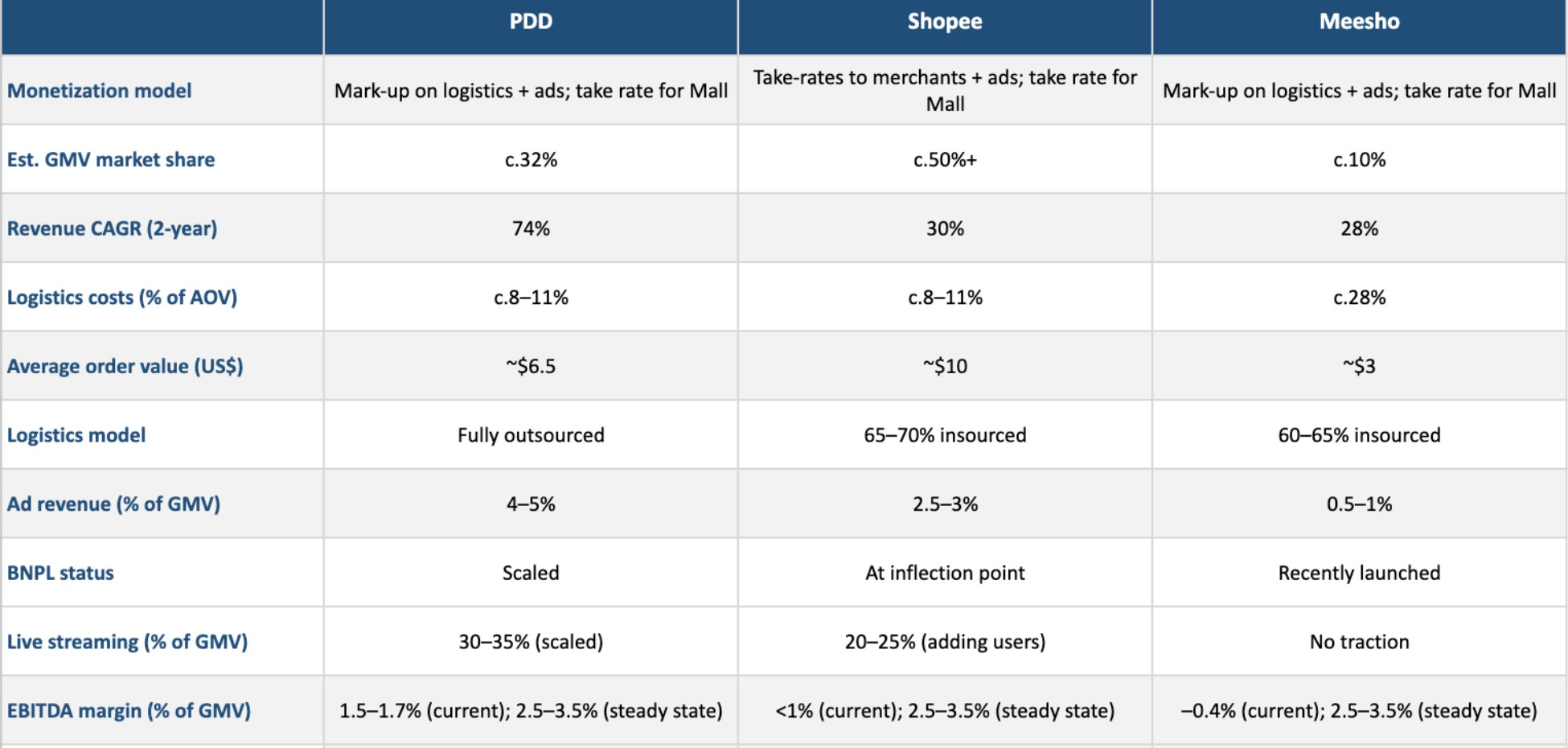

Pinduoduo in China, Shopee in Southeast Asia and Meesho in India run the same business: asset-light marketplaces specializing in cheap goods, slow delivery and monetization through logistics mark-ups, advertising and installment credit rather than retail margins. Temu and Shein, expanding in the U.S. and Europe, are further variations on the same theme.

E-commerce has historically produced radically different business models even within the same country. Amazon and JD.com hold inventory and run their own fleets. Alibaba and eBay operate pure marketplaces. Tmall charges transaction fees; Taobao lets merchants pay for search prominence. Yet when it comes to serving the price-obsessed mass market through an asset-light structure, geography has produced convergence: the same thin-margin, ad-and-credit model discovered independently in Hangzhou, Singapore and Bangalore.

Once a platform makes that choice, the business model is no longer a choice. Physics and capital markets are fitting every player into the same corridor.

Reconstructions of Chinese platforms’ accounts suggest commissions plus advertising amount to roughly 4-5% of gross merchandise value for Alibaba and Pinduoduo, close to 10% for short-video marketplaces like Douyin. Pinduoduo’s EBITDA margins on GMV sit in a 0-4% band. Meesho’s prospectus puts its marketplace contribution margin at just under 5% of net merchandise value; group-wide EBITDA hovers around break-even.

Pinduoduo is further along than Shopee, and Shopee is further along than Meesho. Watching them is like watching the same company at different stages of its life. If three platforms operating under radically different regulatory regimes and competitive pressures all land on low-single-digit operating margins and a reliance on advertising and credit, a fourth is unlikely to find 15% margins through clever execution.

The feature consumers prize most is not brand or speed but low prices. Years of inflation since the pandemic have left lower-income households feeling worse off even where incomes held up. Analysts report a structural shift towards value platforms and unglamorous categories like groceries and pet supplies.

Meesho describes itself as built around “everyday low prices,” serving customers whose typical order is barely a few dollars. Average order values fell from 337 rupees ($3.75) in FY23 to 265 rupees ($2.95) in the first half of FY26. Shopee is the place for promotions across Southeast Asia. Pinduoduo built its franchise inland via group-buy gimmicks. Temu undercuts Western marketplaces by double-digit percentages.

Serving this market imposes constraints, starting with the physics of moving parcels. A basket worth tens of dollars can support fast delivery; a basket worth three dollars cannot.

Logistics accounts for roughly a tenth of order value in China and ASEAN. In India, an executive said it consumes close to a third – around a dollar per shipment where average orders are worth barely three or four.

Value-platform customers tolerate week-long deliveries, allowing networks to reorganize around long-haul batching and fewer fulfillment nodes. Meesho’s logistics arm prioritizes cost over speed. Logistics is a quasi-fixed tax on each tiny basket that ingenious routing can shrink but not eliminate.

Capital markets throws its own constraint wrench to the mix. E-commerce has passed its pandemic peak; sector valuations sit near long-run averages. China’s quick-commerce arms race is instructive: GMV could reach 1.4 trillion yuan ($198 billion) by mid-decade, nearly a tenth of physical retail. The subsidy battle dented earnings; aggregate profits at major platforms fell by more than a fifth. JD.com is modelled on net margins of 2-3% and GMV yields below 1%.

Investors have stopped paying for stories and hopes about 10-15% margins on mass-market GMV. Platforms clip a low-single-digit percentage on throughput and rely on side businesses for real profits.

Pinduoduo charges no commission on most sales, Meesho goes a step further and completely avoids commissions on sales, both instead earning via logistics mark-ups and advertising. Shopee is drifting the same way. Meesho holds no inventory, owns no brands and monetizes through logistics enablement and sponsored listings.

The structure of offline retail reinforces this. Three-quarters of Indian retail is unorganized; two-thirds of Indonesian sales are unbranded; China splits roughly half and half. In the U.S., branded chains dominate. All three platforms have grown by turning informal suppliers into formal marketplace sellers. Their core marketplaces skew to unbranded goods; their “mall” sections for brands are side-cars. Meesho’s average order values fell 20% in two years as low-ticket goods came online. About 88% of its users are outside India’s top eight cities.

Platforms aren’t able to differentiate through supply. An executive described how competitors hunt “Pareto sellers” — systematically identifying rivals’ best-selling products and onboarding those vendors. Shopsy, a Meesho-rival built by Flipkart, scouts Meesho’s top listings; Meesho does the same; Chinese platforms pick through each other’s leaderboards. Supply differentiation lasts as long as it takes to call a vendor in Surat or Guangzhou.

Algorithms offer superficial variety, to be sure, but no escape. One platform pushes new vendors to the top; another favors proven products. Both lead to identical economics. In Meesho’s case, three-quarters of orders originate from algorithmic recommendations. What matters is that the feed exists as a canvas on which suppliers pay for prominence.

Underneath sits industrial “value engineering.” An executive described how platforms achieve rock-bottom prices through systematic corner-cutting. A 200-rupee ($2.22) dress uses cheaper fabric than a 250-rupee competitor, skips the neck patch, uses single-thread hemlines; bags are glued not sewn; embroidery removed.

Consumers are noticing. Tier-two shoppers rate Meesho quality higher than Shopsy despite identical prices and suppliers, according to industry executives. But this doesn’t translate to pricing power. A platform charging 10% more for “better quality” would hemorrhage users overnight. No branded retailer can offer 200 rupees dresses while maintaining standards on stitching and compliance. A brand competing at those prices would cease to be a brand.

Advertising is the first side business that makes this viable. Sponsored listings account for 1-3% of GMV for Indian marketplaces, 4-5% for Alibaba and Pinduoduo, close to 10% for short-video platforms. The 2-3% operating margin on commerce sits atop a separate advertising business converging on mid-single-digit GMV shares.

Cheap goods and subsidized shipping attract users; recommendation engines turn browsing into an endless feed; merchants pay for placement. Goods sell at two or three points above cost. The profit comes from selling attention back to suppliers.

Credit is the second, more consequential side business. Card penetration in emerging markets is low and skewed rich. Broker reports forecast high-double-digit annualised yields on short-tenor BNPL loans after funding costs and losses.

China’s super-apps are the mature version: hundreds of millions run up BNPL balances in the commerce interface, funded by money-market funds and bank credit lines. Shopee operates growing lending books to consumers and merchants.

India is more improvised – formal BNPL is expanding cautiously, but cash on delivery functions as unofficial credit. Meesho co-founder and chief executive Vidit Aatrey told The Arc that customers prefer cash on delivery, or CoD, for its “built-in delay,” which effectively turns it into “a five-day loan.”

These platforms are ad and credit machines fronted by a marketplace. The marketplace gets users to show up; the economics live in monetising attention and balance sheets. Chinese players run embedded wallets and BNPL products. Southeast Asian platforms mix in-house lending with local partners. Meesho leans on CoD and short-tenor loans. Price-sensitive users are acquired through cheap goods; their purchases and borrowing capacity are sold to merchants and financiers.

Food delivery and instant commerce in China carry high frequency and low order values; platforms treat them as marketing, not profit centers. By 2030, food delivery could reach 2 trillion yuan; instant delivery another 1.5 trillion. Platforms lost tens of billions on these at the subsidy wars’ height — framed as customer-acquisition costs justified if they drive traffic to travel and hotels, where EBIT margins hit the high teens or low 30s.

China’s regulators balance platform profits against support for small firms. Temu faces tariff fights and de-minimis tweaks. India’s infrastructure and cash dependence make logistics unusually heavy. These matter for execution. They don’t change the maths of tiny baskets.

Indian strategists talk about a “king consumer” awakening as rates fall and wages rise. The same research caps long-run operating margins in the low single digits and assumes most profit comes from advertising and adjacencies, not retail.

Geography, income and regulation were supposed to produce three different answers. Instead they produced variations on one theme: the 3% endgame in which e-commerce becomes a thin utility layer, clipping a few points of GMV and relying on attention and credit for real profits.