Is India the Global Anti-AI Play?

Follow the money.

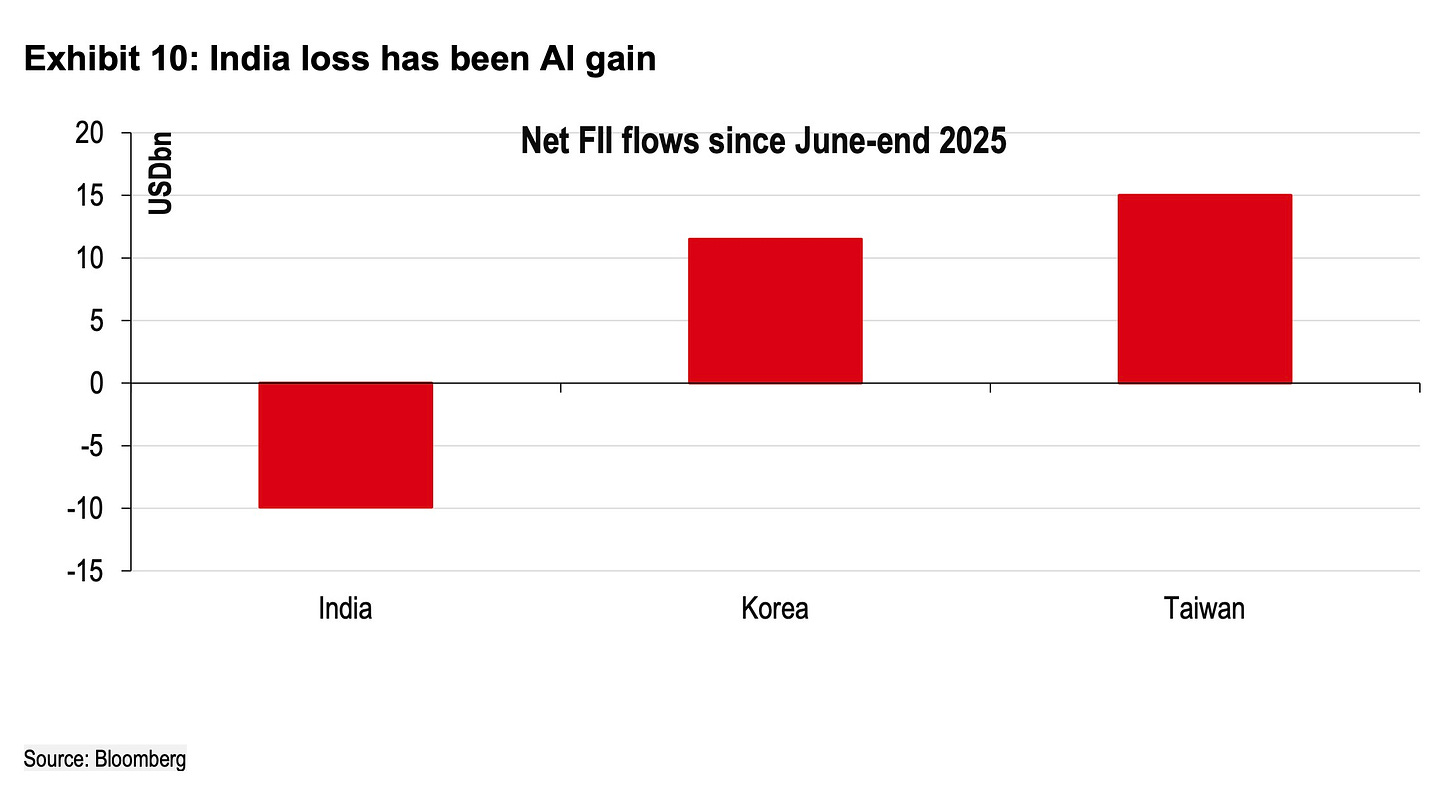

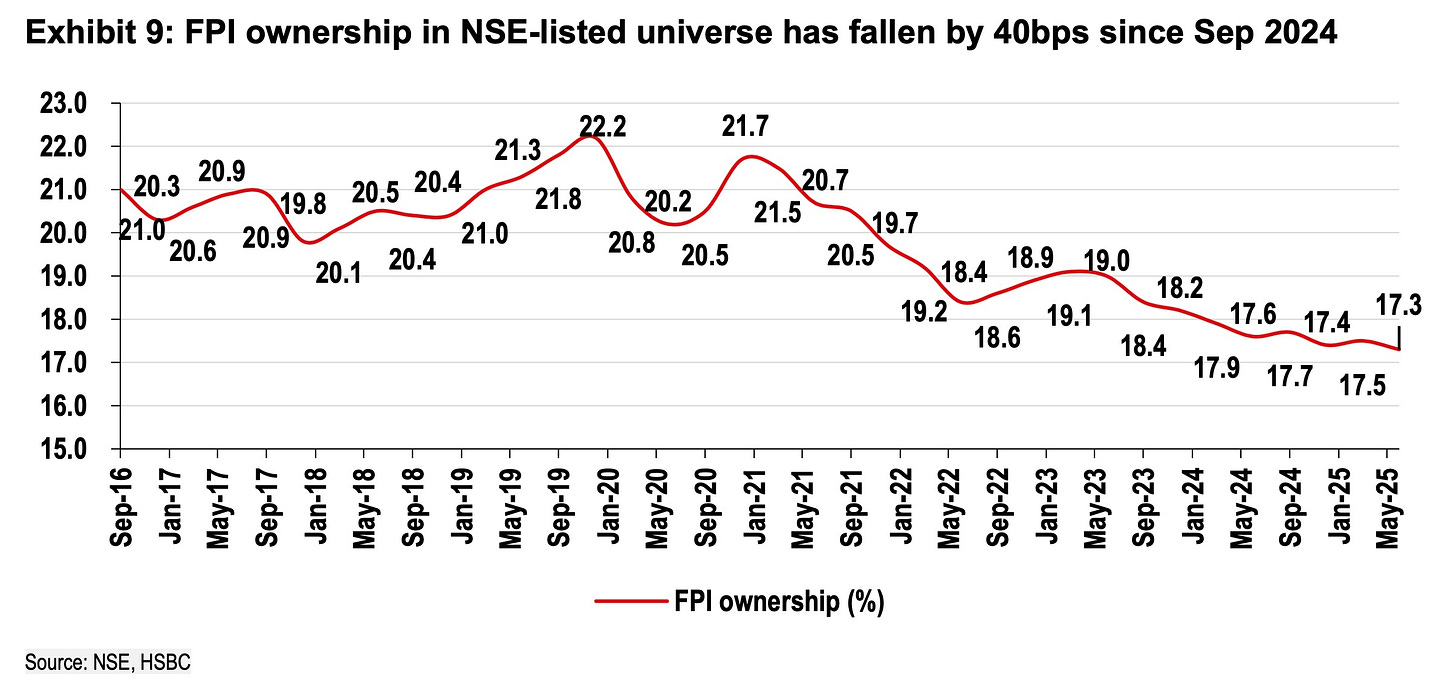

Foreign institutional investors have pulled nearly $30 billion from Indian equity markets over the past twelve months. A huge chunk of that money has moved to Korea and Taiwan. Foreign portfolio investor ownership in stocks listed on India’s National Stock Exchange fell from 22.2% in September 2024 to 17.3% in May 2025. That decline of 490 basis points over eight months represents one of the steepest sustained withdrawals from Indian markets in over a decade. What gives?

Taiwan absorbed $15 billion of net foreign inflows in the third quarter of 2025 alone. It’s the largest quarterly inflow on record for Taiwanese equities. Fund positioning in Korean markets simultaneously reached levels not seen since 2015. The simultaneity of these movements suggests a deliberate reallocation rather than broad emerging market weakness. Money left India and arrived almost immediately in Northeast Asian technology markets.

HSBC has a strong thesis on what happened. Global investors, the bank wrote in a report this week, increasingly view India through the lens of AI economics. India is being positioned as a global anti-AI play, the bank’s analysts say, citing conversations they held with many global investors.

India’s equity markets face selling pressure not because of conventional valuation concerns or earnings disappointments but because investors are making structural bets on how AI transforms economic comparative advantage. India employs roughly 20 million people directly and indirectly in IT services. The sector represents the country’s largest white-collar employment category and contributes materially to export revenues.

Services account for 55% of Indian gross domestic product, compared to 18% for agriculture and 27% for industry. Financial services, real estate and professional services together represent 42% of GDP. The concentration in knowledge work creates exposure to AI-driven productivity improvements that potentially reduce demand for human labor.

HSBC estimates that digital AI agents cost approximately one-third as much as human agents for customer support and certain mid-office functions. Early deployments in collections, customer onboarding and basic financial services tasks have demonstrated both cost savings and volume increases.

Global tech giants will spend $2 trillion on AI infrastructure between 2025 and 2030, according to consensus estimates for Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Oracle compiled by Visible Alpha. Annual capital expenditure by these four companies is projected to rise from $300 billion in 2025 to $500 billion in 2030. Depreciation charges alone will reach $300 billion by 2030.

This spending creates an economic ecosystem centered on GPU computing, data center operations and enterprise AI implementation. India’s participation in this ecosystem remains minimal. The Indian government launched an AI Mission in March 2024 and committed $1.25 billion over five years. Private sector investment beyond two recent announcements by local conglomerate Reliance Industries and consultancy giant Tata Consultancy Services represents a negligible fraction of the global total.

The capital flows reveal the market pricing in this asymmetry ahead of visible economic damage. Indian IT services companies have reported slowing growth and reduced hiring but not yet material revenue declines or workforce reductions. The leadership at major Indian banks and financial institutions told HSBC they remain cautious about aggressive AI adoption. (They say they are concerned about customer data security, regulatory uncertainty and unclear costs for agentic AI systems.) Most Indian companies are currently using AI to improve service quality and increase transaction volumes rather than reduce headcount. HSBC analysts estimate Indian companies are 12 to 18 months away from significant AI adoption for mid-office and back-office functions including loan approvals, policy administration, supply chain management and financial accounting.

The market appears to be front-running a transition that has not fully materialized in employment or earnings data. Foreign investors have reduced their India holdings by nearly 500 basis points over eight months while domestic mutual funds and other institutional investors have absorbed most of the selling. Domestic buyers added roughly $40 billion to Indian equities in calendar year 2024 and have continued buying through 2025. The divergence between foreign and domestic investor behavior creates a natural question about who is correctly pricing India’s position in an AI-dominated global economy. Foreign capital has moved decisively toward markets that benefit from AI infrastructure spending. Domestic capital continues to accumulate shares in an economy where 55% of output comes from services that AI may partially automate.

But! There’s a silver lining, maybe. HSBC says three potential catalysts could reverse foreign institutional selling and restore inflows to Indian markets. Fund positioning in Korea and Taiwan has become crowded. Any negative developments in AI investment sentiment or semiconductor demand could trigger rapid unwinding of these positions. Rotation into emerging markets has not occurred despite a weakening U.S. dollar and resumption of Federal Reserve rate cuts. India would likely capture disproportionate inflows if broader emerging market rotation begins. U.S. tariff policies will have limited direct impact on Indian corporate earnings but any positive trade developments could bring back investors who have moved to the sidelines rather than actively reallocating to other markets.

The positioning data suggests global investors are making a binary bet. Either India’s services-based economic model faces structural decline as AI automates knowledge work, or the market has overreacted to a technology transition that will take years to fully impact employment and create offsetting opportunities in AI implementation services.

Good analysis. I read your dispatch

on Bernstein view on India as well. I fully agree your assessment.

In January 2025 I wrote a blog "Has India missed the Artificial Intelligence bus?'

https://lovekeshchandra.wordpress.com/2025/01/25/has-india-missed-ai-bus/

Many of points mentioned in Bernstein's views were also my reason in the Blog!

HSBC's anti-AI play thesis is brillant - the idea that India's 55% services GDP concentration creates structrual exposure to AI disruption is something most analysts are missing. What really gets me is the timing disconnect you point out: foreign money is leaving now, but Indian companies won't face major AI adoption for another 12-18 months. Either foreign investors are way ahead of the curve or they're panicking into Korea/Taiwan just as those markets get crowded. The domestic vs foreign investor split is fasinating though - if local investors keep buying while foreigners sell, that's a huge divergence in who's right about India's AI vulnerability.