Weighing the Cost of Smaller Appetites

As GLP-1 drugs go generic in India, the same consumers who made food delivery profitable might start skipping meals.

Urban India’s rising incomes have fed a decade-long boom in smartphone food ordering, as affluent consumers turned their impulse cravings for restaurant meals and quick groceries into the operating leverage that built Zomato and Swiggy. The onset of GLP-1 drugs threatens to clip that growth just as these businesses are being priced as permanent winners and expanding into broader India.

India houses about 101 million diabetics and approximately 350 million people living with obesity. Anti-obesity drugs have become the fastest-growing therapy in the Indian pharmaceutical market, and GLP-1 revenues are projected to surge from roughly $147 million in fiscal year 2026 in India to approximately $1.42 billion by fiscal year 2031, according to Goldman Sachs, driven by a 40-fold increase in volumes.

Patent expiry for semaglutide, the active ingredient in both Wegovy and Ozempic, in March 2026 is expected to trigger India’s familiar generic manufacturing cycle. At least ten local producers are expected to enter the GLP-1 supply chain by next year, Novo Nordisk executives said at a recent conference. Between 10 and 15 million Indians will likely be taking GLP-1 drugs by fiscal year 2029, UBS projects, including 4 to 6 million using them specifically for weight loss rather than diabetes management. Indian generic versions will cost 90 to 95% less than American prices, industry executives say.

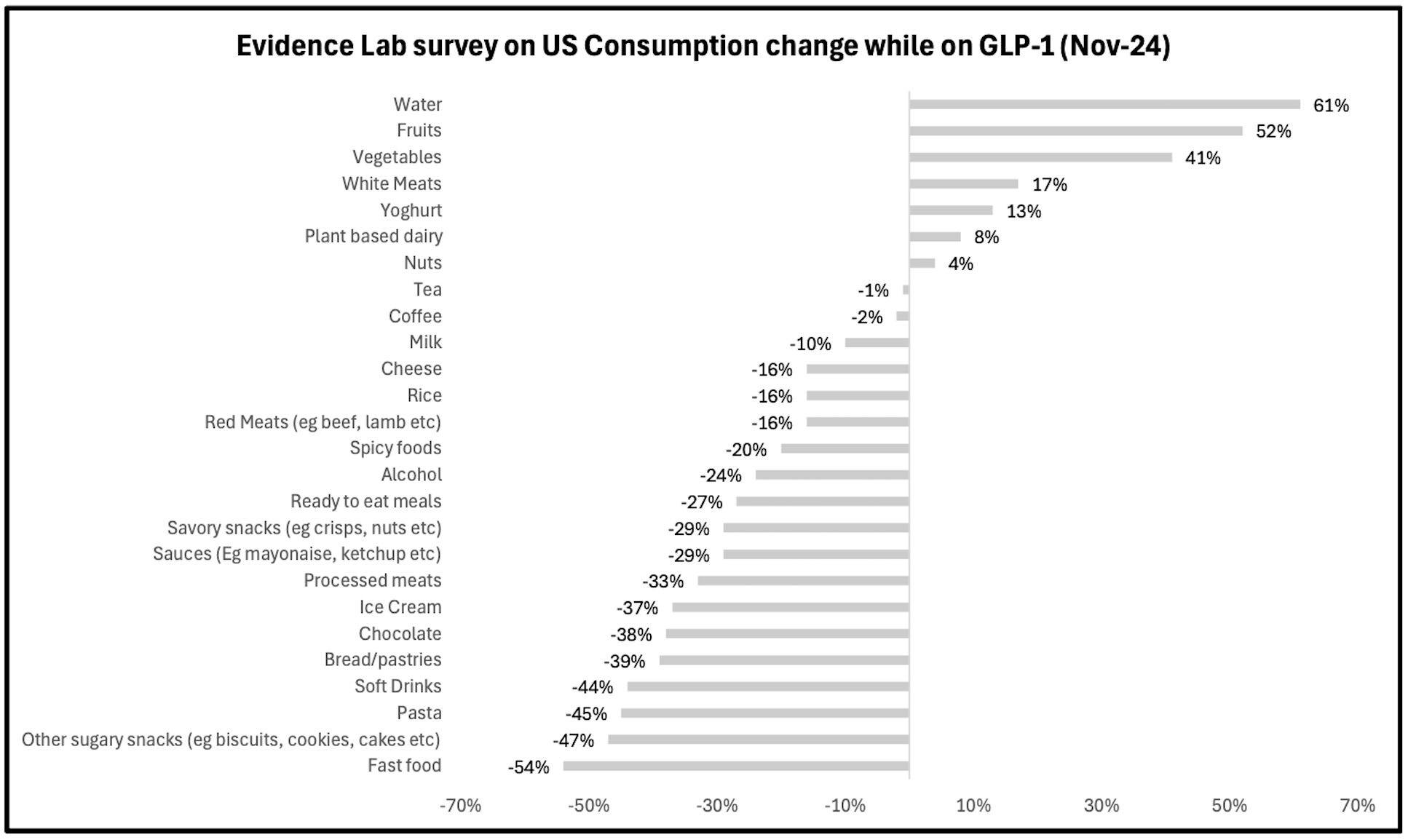

American GLP-1 users cut daily intake between 250 to 800 calories, or a tenth to a third of average adult consumption, concentrating reductions on fast food, sugary snacks, fizzy drinks and alcohol. Households with at least one GLP-1 user reduced grocery spending by 6% within six months of starting the medication, according to research from Cornell University and consumer insights firm Numerator covering 150,000 American households. Higher-income households reduced spending by 8.2%.

Dining patterns have also shifted measurably. Fast-food restaurant visits dropped 8.6% while breakfast declined 4% and dinner fell 6%. Purchases of baked goods dropped between 6.7 and 11.1%. Savory snacks declined 11%. Snacking frequency among GLP-1 users fell 58%. Over 60% of users reported visiting restaurants less (PDF) or much less frequently since starting the medications.

Analysis of US packaged food companies estimates that widespread GLP-1 adoption would reduce annual industry growth by 20 to 30 basis points overall and 30 to 35 basis points in high-sugar and high-carbohydrate categories, accumulating to roughly 145 basis points of cumulative drag by 2028.

India’s consumer internet model amplifies this risk because digital platforms sit atop the exact consumption categories most vulnerable to GLP-1 disruption. American exposure spreads across restaurant chains and beverage manufacturers, but Indian exposure clusters in Zomato, Swiggy and quick-commerce operators. The typical GLP-1 patient is affluent, urban and digitally savvy, a profile that closely matches the heaviest users of food delivery platforms who generate the highest frequency, largest tickets and best margins through premium categories and branded snacks purchased via quick commerce.

GLP-1 drugs could reduce long-term volume growth by 1 to 2% for companies including Jubilant FoodWorks, Varun Beverages, Nestlé India and Britannia due to their calorie-dense product portfolios, UBS recently warned clients in a note. Each percentage point of volume at risk translates to 7 to 10% of market value for quick-service restaurants, while food delivery platforms face even steeper decline because they amplify consumption patterns in these categories. A 1% change in long-term volume growth can shift platform valuations by 2 to 3%.

In the US, Nestlé has become the first major consumer packaged goods company to launch products specifically designed for GLP-1 users through its Vital Pursuit frozen meals and Boost Pre-Meal Hunger Support drinks. The moves came after companies began reporting measurable impacts. Walmart chief executive Doug McMillon told investors late last year that the retailer was experiencing margin pressure from GLP-1 growth. Around the same time, Kraft Heinz projected organic sales would decline between 1.5 and 3.5% during fiscal year 2025, something it partially attributed to reduced consumption among GLP-1 users.

Food delivery growth has already decelerated below 20% in India as app-based ordering matures, leaving platforms dependent on geographic expansion, premiumization and grocery sales for momentum. Gross order growth is projected around 17 to 18% going forward, and once GLP-1 generics arrive, sustained growth above 20% will become difficult. Affluent urban Indians reducing consumption will disproportionately withdraw demand from digital channels rather than physical kirana shops because their discretionary calories flow through apps rather than neighborhood stores.

Top executives at Indian firms say they have not seen any discernible impact on orders or basket composition yet and consider the topic too early to judge. The immediate headwinds they discuss remain conventional: weak rural demand, election disruptions, an unusually wet monsoon and ongoing negotiations over discounts and take rates.

To be sure, behavioral constraints may limit adoption speed more than chemistry or pricing in India. Doctors in the country rarely treat obesity as a disease, cultural norms discourage patients from seeking treatment and medical education around GLP-1 drugs remains inconsistent across the country. That’s why only low single-digit penetration of the addressable population is expected by the early 2030s despite dramatic price reductions and India’s massive disease burden.

American adoption provides some reference case, nonetheless. Usage doubled from 5.8% of adults in February 2024 to 12.4% by mid-2025, according to Gallup surveys, corresponding to a decline in the national obesity rate from 39.9% in 2022 to 37% in 2025. Morgan Stanley projects approximately 24 million Americans will use GLP-1 drugs by 2035.

In scenarios where GLP-1 adoption reaches only a few percent of the obese and diabetic population by the early 2030s, India’s per-capita calorie consumption could decline by approximately half a percent annually for several years, according to Bernstein, concentrated in restaurant food, packaged snacks and sugary beverages rather than home-cooked meals.

India’s decade of consumer internet growth transformed urban eating habits into platform profits through tens of millions of smartphone taps. Cheap weight-loss drugs won’t destroy that model but will thin it at the margins that matter most for valuations. The wealthiest users who order most frequently and spend most generously are the same demographic most likely to inject or swallow their way to smaller appetites.

The structural growth investors model for food delivery becomes incrementally thinner each year while profit pools in GLP-1 manufacturing and pharmaceutical exports become correspondingly fatter, turning India into both a major consumer and supplier of the drugs reshaping global food consumption.

This is an excellent piece

In one of my earlier posts i lamented the decline of family kitchen bon homie as food platforms proliferated. This well researched piece raises a hopeful mirror, one that points to the return of kitechen ritual on the back of proliferating GLP-1. My substack post in this link: https://open.substack.com/pub/abhijitchaudhuri/p/the-silent-kitchen-paradox?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=21hjtw