Peak Exits, Peak Anxiety

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.

In many ways, the startup investing business is unique. Whether you bet on the right thesis, right team, and right market doesn’t become clear for four to six years, if not longer. 2025 was a great year for the Indian venture ecosystem, delivering the largest number of major IPOs and impressive returns for investors on dealmaking they did nearly a decade ago. The profit-bookings, paper gains and enthusiasm, however, also helped mask the current state of affairs for the ecosystem, which had one of the most concerning, anxious and soul-searching years in over a decade.

The Indian startup market is the third largest in the world by participant count. But unlike the U.S. and China, the two largest markets, India has historically performed poorly in delivering returns. “Returns on capital in India have sucked historically. If you look at the market-leading internet companies, whether it is Google, Facebook, Alibaba or Tencent, revenue for them got bigger than cost more than a decade ago. You had a great legacy of last 17-18 years of materially profitable internet companies. So returns on equity in the internet got really high and the returns for investors have been really high. But that did not happen in India,” Scott Shleifer, former venture lead partner at Tiger Global, told a group of entrepreneurs in early 2023.

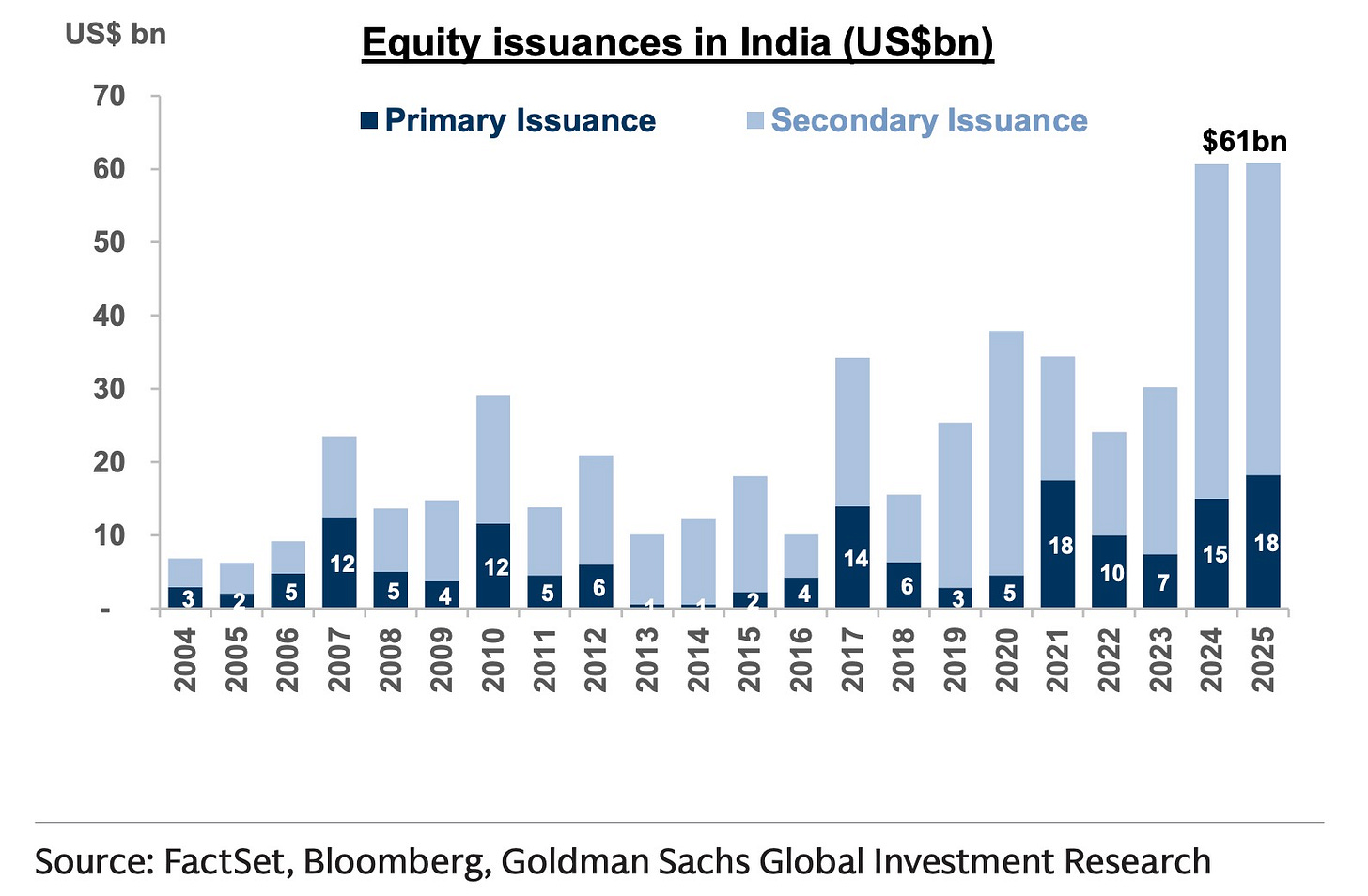

For the longest time, the criticism Indian venture investors faced was whether India would ever deliver enough exits, whether Indian companies would ever go public, and whether Indian public markets had the appetite for new-age startups. The Indian market started to answer some of these questions in 2021. A wave of new-age firms, including Zomato, Policybazaar, Paytm and Nykaa, went public that year, delivering great returns for their early backers.

But Indian markets have been brutal in many ways. Paytm and Freshworks are still trading considerably below their debut listing prices. Zomato, the top public Indian internet firm, has created more than 70% of its value after the IPO, much of it after the majority of venture firms exited the company.

In this way, 2025 was a great year for the ecosystem. Groww and Meesho delivered stellar returns and months into their debuts are still trading significantly higher than their listing prices. Pine Labs, Urban Company, Lenskart and Physicswallah were other notable successful debuts. These have all been amazing lagging indicators for how the ecosystem finally stood tall. A group of other impressive companies, including Razorpay, PhonePe, Zetwerk, and Zepto, are all expected to go public in the next four quarters. So good times are set to continue, in a way.

The concerning factors are those that will not be publicly apparent for a few years to come. The pipeline of potential big hitters from the last four to six years looks very thin. Many of the impressive SaaS startups that the investors backed between 2018 and 2022 are looking increasingly less relevant and appealing. The ecosystem is also yet to publicly confront the reset in valuations and erasure of paper gains from so many startups that raised at very high valuations between 2021 and 2023, but are suddenly nowhere to be heard.

Venture partners in the U.S. market have been able to wrestle with this global reality because they had enough other portfolio winners, crypto-things, and some AI investments they made in exuberant times that suddenly made everything more than worthwhile.

Indian venture firms don’t have that privilege. You can count on two hands all the impressive, might-probably-make-it deeptech and AI startups from India founded in the last decade.

VCs in India have been increasingly scrambling to back such deeptech and AI startups. Over the last two years, the majority of VCs, including all the tier-one firms, have shown reluctance to back most non-AI ventures, but the universe of startups they can back hasn’t meaningfully grown. SoftBank, which has been focusing on AI deals in recent years and has deployed billions in India, has made zero new investment in the South Asian nation in the last three years.

There is general pessimism among many investors about anything fintech because of the many regulatory changes – or clarities – pushed by the Indian central bank. Jupiter and Fi, two startups that raised significant capital for building neobanks, are nowhere to be found. Byju’s and Unacademy killed much of the appetite for edtech in the country. The largest Indian e-commerce startup is always listing that particular year, reportedly, but its finances are always a few years away. Some global investors who were still willing to underwrite all the regulatory pains in India were hit with a slap when Dream11’s business overnight evaporated.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Peak XV is increasingly focusing its attention on the U.S. market. Let that sink in: The largest venture capital firm operating in India has to look elsewhere for dealmaking. Lightspeed is looking to raise a smaller fund than the $500 million it raised for India earlier because, at the end of the day, the Indian market doesn’t offer the kind of opportunity to deploy that much capital anymore.

Other venture firms have taken the opposite approach, continuing to raise larger funds and developing, for the first time in their existence in India, the conviction and expertise to invest in late-stage startups – because, in part, why risk less management fee.

These shifts in strategy are making many partners uneasy, some of whom have left their firms in the last year or so to start their own. The failure to have succession plans at many of these venture firms has meant that many mid-level executives departed last year because they don’t see any promotions or room for growth coming for years.

The Indian venture ecosystem enters 2026 caught between two realities: the celebratory exits of bets made a decade ago and the quiet anxiety over what the next decade’s returns will look like. Sadly, the former will dominate the headlines.

Interesting read, thanks!

Did you have a piece looking at the Dream11 decision? Was it the right call or the wrong call by the govt/or what more nuance is there to it?